theartsdesk Q&A: Director Barrie Rutter | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Barrie Rutter

theartsdesk Q&A: Director Barrie Rutter

The artistic director of Northern Broadsides on the company's first eventful 20 years

In 1992 Northern Broadsides, the Halifax-based theatre company founded by Barrie Rutter, staged its first production, Richard III. Rutter (b 1946), an established actor who had worked with some of the most distinguished names in theatre such as Jonathan Miller, Terry Hands, Peter Hall and Trevor Nunn, directed the show and also played the title role.

Admittedly that may sound far from innovative today’s theatre audiences who are used to actors such as John Simm and Christopher Eccleston playing Hamlet, but 20 years ago it was quite a radical departure. There were of course roles from 20th-century writers as diverse as Harold Brighouse and Shelagh Delaney which required northern voices but an actor hoping to play a Shakespearean king or queen would normally have to abandon the slightest trace of a regional accent or dialect at the audition.

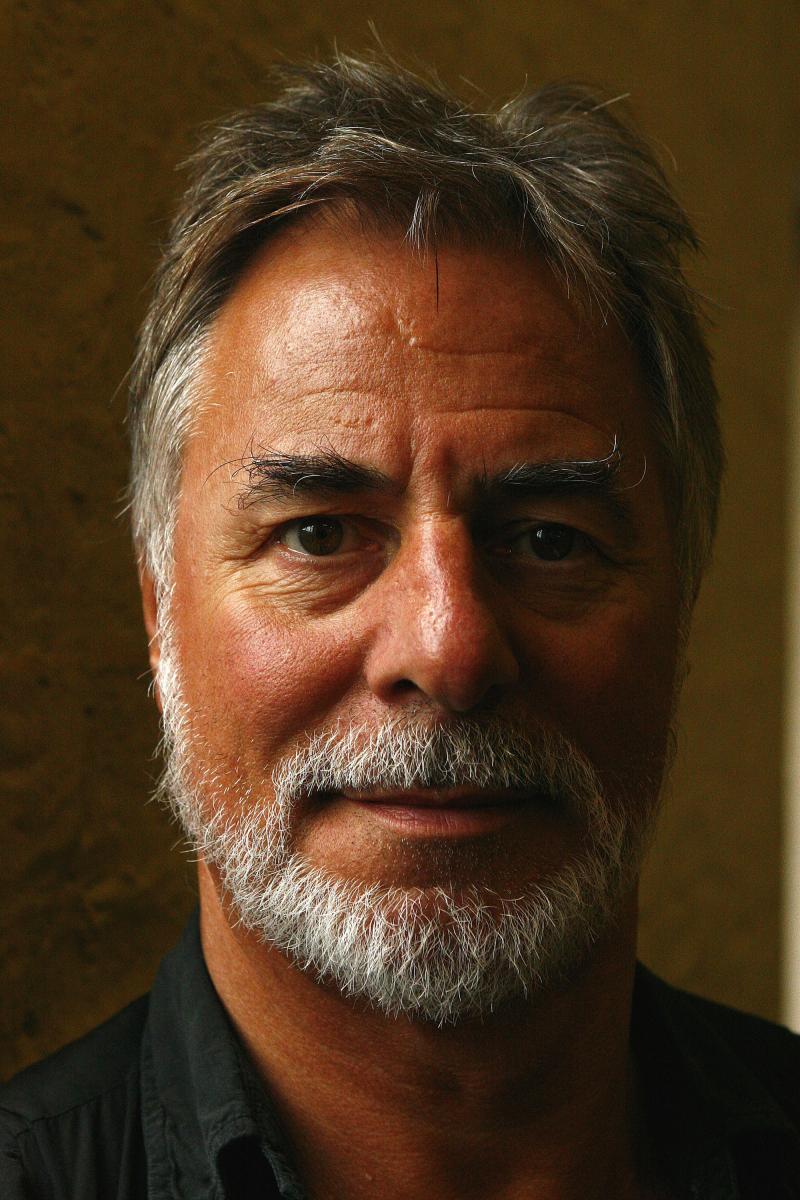

Rutter, a bluff straight-talking Yorkshireman, has remained firmly at the helm of Northern Broadsides, deftly combining the roles of artistic director, actor and director, in addition to making the occasional appearance of television – he was last seen on the small screen alongside Alison Steadman in Fat Friends. The company has toured extensively all over the world, presenting mainly Shakespeare and classical plays, with the aim of making “difficult” texts accessible. The practicalities of touring, not to mention budgetary constraints, have meant the company has had to adopt a pared-down, no-frills attitude which, far from detracting from its work, has increased its reputation for coherence and unpretentiousness. Northern Broadside productions are far from dull. Classic texts are often adapted to bring them bang up to date – such as its version of Oedipus, set during the foot-and-mouth crisis of 2001. The company also created a stir in 2009 when Rutter took a punt on rookie Shakespearean actor Lenny Henry, who joined the ranks to play Othello (pictured above with Rutter)

Rutter, a bluff straight-talking Yorkshireman, has remained firmly at the helm of Northern Broadsides, deftly combining the roles of artistic director, actor and director, in addition to making the occasional appearance of television – he was last seen on the small screen alongside Alison Steadman in Fat Friends. The company has toured extensively all over the world, presenting mainly Shakespeare and classical plays, with the aim of making “difficult” texts accessible. The practicalities of touring, not to mention budgetary constraints, have meant the company has had to adopt a pared-down, no-frills attitude which, far from detracting from its work, has increased its reputation for coherence and unpretentiousness. Northern Broadside productions are far from dull. Classic texts are often adapted to bring them bang up to date – such as its version of Oedipus, set during the foot-and-mouth crisis of 2001. The company also created a stir in 2009 when Rutter took a punt on rookie Shakespearean actor Lenny Henry, who joined the ranks to play Othello (pictured above with Rutter)

Over the years Rutter and the Northern Broadsides have received numerous awards, culminating in the country’s most lucrative arts prize – Creative Briton 2000 – which was awarded to Rutter with a cheque for £100,000 to be spent on the company. As the company celebrates its 20th anniversary and its latest production, Love’s Labour’s Lost, opens at the New Vic Theatre in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Rutter talks to theartsdesk.

HILARY WHITNEY: How did you become interested in the theatre?

BARRIE RUTTER: I had a very unhappy home life. Me and my dad lived with his parents in their two-up two-down on the fish dock in Hull and so when I got to the grammar school, which was the other side of Hull, and it afforded me all these societies to join plus all the sports, it was like a playground for me. It was a big deal for me to get to grammar school with the school uniform and all that. Every day, until I got a bit older, I had to run the gauntlet because all the lads who I grew up with down the same street went to the local school which was literally 30 seconds away from their front door, so walking down the street in a school uniform and a satchel full of homework wasn’t easy. But I loved school because it afforded me time not to go home.

Eventually in my fourth year I got into, or was dragged into, the drama society. My teacher said, “You’ve got a bit gob in class, put it to use in the school play,” so I got on stage and played the Mayor in The Government Inspector and I just loved it. I’m not saying I was good, I’m not talking about talent, that was up to other people to decide, but I am talking about being comfortable on a stage – I knew I loved it and so I went on from there. I joined the National Youth Theatre and when I left school I went to the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. In 1968 I was in The Apprentices, which was Peter Terson’s follow-up play to Zigger Zagger, and sort of written for me, and that was my launch into the profession. (Pictured above: Rutter as Shylock in Northern Broadsides production of The Merchant of Venice, 2004)

Eventually in my fourth year I got into, or was dragged into, the drama society. My teacher said, “You’ve got a bit gob in class, put it to use in the school play,” so I got on stage and played the Mayor in The Government Inspector and I just loved it. I’m not saying I was good, I’m not talking about talent, that was up to other people to decide, but I am talking about being comfortable on a stage – I knew I loved it and so I went on from there. I joined the National Youth Theatre and when I left school I went to the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. In 1968 I was in The Apprentices, which was Peter Terson’s follow-up play to Zigger Zagger, and sort of written for me, and that was my launch into the profession. (Pictured above: Rutter as Shylock in Northern Broadsides production of The Merchant of Venice, 2004)

I don't suppose your family had ever considered you might become an actor?

It was a maritime town and my dad wanted me to be a marine engineer on big boats. He’d been in the Navy and worked on the fish docks all his life so all his stories were maritime and he thought that I should be a marine engineer and see the world, but I showed no inclination whatsoever for physics. I wasn’t interested in cars or anything like that. I just did sport and enough at school to earn me five O levels to go back into A levels and from when I was 15 and a half, my whole energy went into acting.

Did you have much opportunity to see any theatre when you were growing up?

Nothing much came to Hull. I was doing A levels at school and I was wrapped up in the National Youth Theatre and preparing to go to drama college but there weren’t many opportunities to see theatre in Hull, except for visiting companies who did the odd Shakespeare. I remember the New Shakespeare [Company] came with a production of Twelfth Night and of course I didn’t understand a thing, it was all posh.

It was a very naïve world in the early Sixties and I was as naïve as any. When my English teacher said to me, “I’ve had a chat with the headmaster and we think you should go to drama school,” I said, “Oh, all right. I’ll go.” “No, no,” he said. “You have to pass an audition,” and I said, “Well, I’ll pass - what’s an audition?” That’s how naïve it was. And if you jump-cut up to 1991, 1992 when I was setting up my own company, I was equally naïve.

Obviously you use your head but there’s also the Holy Trinity of head, heart and balls

Tell me about your time the National Youth Theatre.

London during the late Fifties and Sixties was a very different time of life. It was thrilling. I mean, I was a Roman sergeant in Antony and Cleopatra at the Old Vic in 1965 with Helen Mirren playing Cleopatra - that was her great launch. She wore this sensational white dress and sure enough, every night a mammary would pop out of one side and the whole of the Roman army would be lined up in the wings to see which one it would be.

Did you enjoy Shakespeare at school?

Oh yes. In 1964, Shakespeare’s quarter-centenary, I played Macbeth at school. I enjoyed the language. I’d already had one year in the National Youth Theatre by then - I did Coriolanus at the Queen’s Theatre earlier that year, so I had a taste of it from Michael Croft. I went back for my final year of school and then went to the [National] Youth Theatre to do Anthony and Cleopatra in 1965 before going to college.

When you were at drama school, how did you imagine your career would be? Did you imagine yourself as a great classical actor?

I had no idea. And I do impress upon you, really, that the naivety and the desire to do well went hand in hand. I always said to myself, "Well, if I find myself out of my depth, I’ll do something else." I didn’t know what else to do and I didn’t know if I would ever get out of my depth, it was just, “This is what I’m going to do and if they don’t like me I’ll get out.”

You were at drama school in Scotland rather than London. Did they take issue with your accent?

Of course they did! I was in a room full of bloody Scots and they told me I talked funny! They did give me a bit of a chip – not that I didn’t have a bit of a chip on my shoulder to start with - but they gave another one so I was balanced. In fact, I left early because I got offered a wonderful job with Michael Croft and a professional arm of the National Youth Theatre playing Nipple in Little Malcolm [and his Struggle Against the Eunuchs by David Halliwell] abroad which was wonderful – first class all round Europe, 1968. Ken Cranham was Scrawdyke. It was terrific and I went back that summer to do The Apprentices, Peter Terson’s follow-up play to Zigger Zagger. (Pictured above, Northern Broadsides' production of The Tempest)

Of course they did! I was in a room full of bloody Scots and they told me I talked funny! They did give me a bit of a chip – not that I didn’t have a bit of a chip on my shoulder to start with - but they gave another one so I was balanced. In fact, I left early because I got offered a wonderful job with Michael Croft and a professional arm of the National Youth Theatre playing Nipple in Little Malcolm [and his Struggle Against the Eunuchs by David Halliwell] abroad which was wonderful – first class all round Europe, 1968. Ken Cranham was Scrawdyke. It was terrific and I went back that summer to do The Apprentices, Peter Terson’s follow-up play to Zigger Zagger. (Pictured above, Northern Broadsides' production of The Tempest)

How come Terson came to write The Apprentices for you?

Yes. The first script came and the main character was called Rutter. Michael Croft said, “Of course this will change but at the moment it’s Rutter.” You see, the original Zigger Zagger, which happened the year previously, was about Stoke City but Michael Croft changed the location to London. It was a brilliant transformation, but instead of being in Zigger Zagger, I was made to play Falstaff in Henry IV Part One and, being aged 20, I huffed and puffed. So Peter Terson wrote this play which was a lot tougher and a lot more cynical. And I said, “It’s a bit dark this, isn’t it, Terson?” and he said, “That’s what you’ve been like for a fucking year.” But it lightened up into the script it eventually became and the main character was renamed Douglas Bagley.

Did you enjoy drama school?

I didn’t have a great time, to be honest. Maybe a lot of that was probably down to me, but you know, I just found it all a bit mini. That’s probably being a bit unfair but I did leave early – and with no regrets.

You’d think, why’s he got that part and not me? He’s dull as dishwater. But he’d be posh

What do you mean by “a bit mini”?

I’d already done two years with the energy of the National Youth Theatre during the summer where there was so much energy and enjoyment and that thrilling sense of acting from your bollocks up. Obviously you use your head but there’s also the Holy Trinity of head, heart and balls, which you got in spades at the Youth Theatre although I wouldn’t have known how to articulate it then. I just simply didn’t enjoy college as much as I thought I would. I had some great times, of course, what student doesn’t have great times, and I went to the Citizens Theatre a great deal, which was down the road and there was also the Close Theatre, which was the studio theatre attached to it, so there was a lot of activity up there. But I was happy to leave early and go round Europe first-class playing Nipple. Who wouldn’t?

And what happened after that?

I was in a production at the Nottingham Playhouse with Jonathan Miller and I worked with Michael Croft because then there was a professional arm of the National Youth Theatre called the Dolphin Theatre Company at the New Shaw Theatre. I did some television - I played the idiot son of Diana Dors for two years in a situation comedy called Queenie’s Castle and then in 1975 I went to Stratford, which was very enjoyable because I was in one of the RSC's most successful productions – Henry V with Alan Howard, directed by Terry Hands. It ran all that year, went to London, then a tour of America, Europe and Britain and when I went back in 1977, it joined the other Henrys - the Henrys IVs Parts One, Two and Three. So you’d walk into the stage door and say, “Which one are we doing tonight?” and the reply would be, “I don’t know, but they’re all fucking called Henry!” Later in the year Trevor Nunn did As You Like It and the same Histories team did Coriolanus, which again was a wonderful production with Alan Howard directed by Terry Hands.

What kind of parts were you given at the RSC?

Rough and ready parts. I was not deemed good enough to have a poetic part, as it were.

Do you think it was because of the way you spoke?

Definitely. You’d look around and you’d think, “Why’s he got that part and not me? He’s dull as dishwater.” But he’d be posh.

But the big turning point in your career was, of course, when you went to the National Theatre and met Tony Harrison.

We’d been rehearsing The Mysteries and Tony had just jetted back from New York having done the libretto for the Janáček [Jenůfa] at the Met and he came into rehearsals and said to me, “I’ve just spent nearly 10 years of my life doing my version of The Oresteia for voices like yours.” Within 10 minutes of that conversation, we were talking about rugby league and the great teams of Hunslet and Hull back in the Fifties and Sixties. I thought, this is a man I could be friends with, and the rest is history. (Pictured above: Northern Broadsides' production of Oedipus, 2001)

We’d been rehearsing The Mysteries and Tony had just jetted back from New York having done the libretto for the Janáček [Jenůfa] at the Met and he came into rehearsals and said to me, “I’ve just spent nearly 10 years of my life doing my version of The Oresteia for voices like yours.” Within 10 minutes of that conversation, we were talking about rugby league and the great teams of Hunslet and Hull back in the Fifties and Sixties. I thought, this is a man I could be friends with, and the rest is history. (Pictured above: Northern Broadsides' production of Oedipus, 2001)

So I did The Mysteries and The Oresteia and then stayed on at the National for Guys and Dolls with Julia MacKenzie. I was Benny Southstreet and I sang the title number and the opening fugue, so I’m on the record. I get about 20 quid a year, I think from sales of the record.

Then Harrison wrote The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus, with a part especially for you.

Yes. The through-line was written for me and Jack Shepherd. We played two Egyptologists – Grenfell who turned into Apollo which was Jack, and I played Hunt who turned into Selenus, the head of the satyrs. I went into a tent as a pith-helmeted Egyptologist and came out as a rabid satyr with foot-long willy. I had a bit of difficulty playing the posh Egyptologist from 1907 but I tried my best and it was all in rhyming couplets so it was my version of RP.

Have you ever played a role speaking entirely RP?

I can’t do RP. Well, they tried to get me to do it at college and I can make an attempt to do it but it’s always phoney. There are actors who can do it better, so why bother casting me? RP is based on the southern English public school and I’m neither of those. I’ve got a voice which is crystal clear but it just has its own sound. It was Tony Harrison, one of the great classic scholars of the theatre, who taught me the energy and dignity of my own voice and it was that, together with performing Trackers in a mill in the north, that gave me the idea to start my own company.

Even Skipton cattle market has been tarted up a bit, although they still do have sheep

The play [Trackers] was written in full formal verse. We’d done it at the National Theatre, we’d done at Delphi and then we’d played it in Salts Mill, just north of Bradford where the natural sound of the play met its people. It was really quite profound and it had a big effect on me. Then I had two big disappointments: one was that a big television job fell through and the other was that a world tour of Trackers got cancelled, so on the strength of two disappointments - you can only kick the dog or drink Scotch so much – I said, “Right, I’m going to do something myself,” although I didn’t know how. My agent said, “You’ll have to ring your accountant.” So I said, “What the bleedin’ hell have I got to ring him for?” and she said, “Because you send him some money and he makes you a company and registers you at Companies House.” “Oh,” says I. So I do all that, again with this great naïvety, but a burning desire to do it – that is, present a classic play with an all-northern cast in non-velvet – and I created that phrase, non-velvet - venues.

What exactly do you mean by non-velvet venues?

Well, non-velvet venues don’t really exist nowadays - even Skipton cattle market has been tarted up a bit, although they still do have sheep. But they’ve more or less disappeared because health and safety is in there, putting its fucking great oar in and also councils are less strapped so if they’ve already got a venue, why would they put the infrastructure [for a drama production] in a mill, just because Rutter fancies playing in a mill? But – and we are the only major touring company that still do this - we still play different shapes all the time. We’ll go from the round to proscenium arch to travserse and then we’ll go to Skipton and then we’ll play the Georgian theatre in Richmond, North Yorkshire where a full-house is 150 people and you can’t have any scenery at all, just actors and costumes.

You must have talked about your idea for a theatre to other actors?

They thought I was mad. Brian Glover said, “Rutter – I think you’re fucking crazy, but I’ll do it.” So he was in the first production, as was Mark Addy, Polly Hemingway, Ishia Bennison, and they all thought, “He’s mad – but we’ll do it.” There were also quite a few of the lads from the Trackers company because I promised them that if there was a part for them they could all be in it. And that was 1992.

Where did the name come from?

When we played Trackers at Salts Mill, where the play met its natural sounding audience, because the play was all written for northern voices, the Guardian review said, “This is a broadside against gentility” or something like that. So I just put Northern in front of Broadsides.

Do you think that performing plays in northern accents…?

That’s bullshit. I’ve never mention the word accent or dialect in any editorial I’ve done – others have. “Oh, you’re the one who does Shakespeare with northern accents.” No. I don’t. I use what I call the northern voice with its alacrity, with its limestone grip consonants and short vowels. Where does the north start and end? I use everyone from Geordies to people from Nottingham.

Well, quite. It’s not as if the North of England is populated by a great sweep of homogenous northerners.

Of course not. I tapped into the energy of the alacrity of the northern voice with, obviously, the vocal and theatrical techniques of the stage to tell a story. I’ve always said, “Kings will speak as commoners.” The difference is that Shakespeare gives them a different syntax. So I deliberately played Oberon when we did A Midsummer Night’s Dream (pictured left) Everybody said, “You’ll play Bottom,” and I said, “No, I’m going to play King of the Fairies and say 'blood' and 'love' and 'much' just the same as Bottom does but obviously with a different syntax."

Of course not. I tapped into the energy of the alacrity of the northern voice with, obviously, the vocal and theatrical techniques of the stage to tell a story. I’ve always said, “Kings will speak as commoners.” The difference is that Shakespeare gives them a different syntax. So I deliberately played Oberon when we did A Midsummer Night’s Dream (pictured left) Everybody said, “You’ll play Bottom,” and I said, “No, I’m going to play King of the Fairies and say 'blood' and 'love' and 'much' just the same as Bottom does but obviously with a different syntax."

Do you think using wholly northern voices makes a production more democatic? If there’s a cockney accent in a production of Shakespeare, it usually belongs to one of the comic characters.

Exactly. That’s exactly what Tony Harrison puts in his sonnets, Them and Uz. There are two sonnets that go together and they’re called Them and Uz. And he says, “I played the comic part, I played the Porter in Macbeth.”

Just as a little side story, when the great furore over Richard Eyre's television film of Tony’s poem V [a poem Harrison wrote after his parents’ grave had been vandalised] was happening and it was mentioned in Parliament – “Who is this upstart poet?” they said – he [Harrison] was the President of the Classical Society of Great Britain! I remember him writing a letter to The Times saying something along the lines of “I was away for the recent furore but it was my study of Greek and Latin that enabled me say fuck, shit and piss and cunt in V,” and he signed the letter President of the Classical Society of Great Britain. A great rejoinder to those poncey bleeders!

Sometimes lines are just meat and two veg – just say them. Now, you have to use skill and delivery, you have to be able to reach the back row, you have to know who you are talking to, you have to know the situation you are talking in, but sometimes it’s just simply meat and two veg. Just say the bugger.

What did you learn from Northern Broadsides' first production, Richard III?

The great surprise really was how the actors and, in particular, the audiences took to it. All the actors said, “You have to do this again.” Brian Glover took me aside after two performances and said, “Rutter, you’re doing something here, you have to do it again.” Now, I never thought they’d be a year two, never mind a year 20. I just thought I had one good idea but to do it I had to form a company and get it off the ground. I got great support – I’m not saying I didn’t, and I’ve always acknowledged the great support I got - but basically nobody else had thought of doing it in 1992. Do it now and people will tell you to piss off because it’s not a new idea but then it was quite revolutionary.

I was naïve – and naivety was courage. Bloody-mindedness was an ally

And was that the first time you’d directed anything?

There was only me who had the vision so no one else could direct it. I had directed a Ken Campbell play at the Shaw Theatre and I’d done little bits and bobs at the National as an assistant director and things like that but this was the first time I’d done anything on this scale. Actors were really willing to put themselves in my hands, as it were, but everyone came out of it with a great and glorious experience. The authorities then said, “OK, we’ll give you some money and you can do it again.” Which was quite amazing in the recession of 1992. I mean, what idiot started his own theatre company in the middle of that recession? I was naïve – and naivety was courage. Bloody-mindedness was an ally.

There must have been problems that you could have never ever foreseen.

Yes. And you came up against them and you said. “This is a brick wall. Oh dear. Well, I’m just going to have to go through it.” The low points all happened in the Nineties with funding - or lack of. I think that at that time I was about the only actor/manager who was asking for the Queen’s shilling in subsidy and there were certain personalities within the Arts Council that didn’t like that. They didn’t want the performer leading – they always wanted to talk to an executive, which of course I’ve got but I was much more of a young Muhammed Ali in the early Nineties - you know, “What’s my name, what’s my name?”

Was there a particular point when you thought, this is it: we’re on a roll, we could just keep going?

Yes. In the second year we did Merry Wives – I dropped the Windsor – with a cast of 16 and we did a full seven-city tour of India. Then the following year, because we were getting invitations to move into a more formal relationship with venues, it stopped being something we just did in the summer and we did various slots throughout the year. But we weren’t fully funded - project funding, that’s what you call it. Play by play. You get the tour in pencil, work out your budget and then you go to the Arts Council for the deficit. In fact, that went on right until 2000 which was as frustrating as hell because we were really popular, but I don’t have a problem with the Arts Council per se - I think it’s a terrific organisation and I wish this government would just fuck off and leave it alone. However, within it there are certain things you battle against and, quite rightly, you should. Then I won the Prudential Award - which was £100,000, the largest private arts award in the country - as the most Creative Briton. It’s a rather pompous title but if you’re not in the competition you can’t win it and I was. All the finalists got £20,000 and I picked up an extra £80,000 as the overall winner and – as I was told – that shamed the Arts Council into funding the company regularly and we’ve been regularly funded ever since.

You’re probably best-known for your Shakespeare but you’ve worked alongside several writers….

Blake Morrison has done six plays for me. The Cracked Pot (pictured right) was the first one, which is the German classic comedy [Der zerbrochene Krug by Heinrich von Kleist] and he also did Oedipus, Antigone, Two Gaffers – we called ours A Man with Two Gaffers, the National called it One Man, Two Guvnors [based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldini] - we did our about six years ago. Then he did Lysistrata, or Lisa’s Sex Strike as we called it, and he recently did the Brontë play, We are Three Sisters, loosely based on Chekhov’s Three Sisters – we discovered that Chekhov actually did know about the Brontёs when he wrote Three Sisters.

Blake Morrison has done six plays for me. The Cracked Pot (pictured right) was the first one, which is the German classic comedy [Der zerbrochene Krug by Heinrich von Kleist] and he also did Oedipus, Antigone, Two Gaffers – we called ours A Man with Two Gaffers, the National called it One Man, Two Guvnors [based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldini] - we did our about six years ago. Then he did Lysistrata, or Lisa’s Sex Strike as we called it, and he recently did the Brontë play, We are Three Sisters, loosely based on Chekhov’s Three Sisters – we discovered that Chekhov actually did know about the Brontёs when he wrote Three Sisters.

What I was going to say is that you seem to particularly enjoy working with poets – Tony Harrison, Blake Morrison and Tom Paulin have all written for Northern Broadsides. Why do you think you are so drawn to working with these particular writers?

Because it’s food. Because I love the big ideas. Because for ill or good I’ve always been a big performer. Not everybody likes it, I don’t care – that’s me and I couldn’t give two monkeys. And I’ve always put body into everything I’ve done. But I love what the stuff asks you to do, like The Mystery Plays which is all in verse, mostly rhymed and you have to carry it in your body - I love that rock 'n’ roll of formal language, whether it’s the Greeks or whatever. It’s always, always been attractive to me.

And how do these collaborations evolve?

It was Tony Harrison who put me on to the fact that Blake had done a version of the Kleist play for the National Theatre and it sat on a shelf for two years. So I got it, read it – and I didn’t like it and didn’t know how to say it to him. Then I read his poem, The Ballad of the Yorkshire Ripper, where he puts all the horrors of the Yorkshire Ripper into ballad form using a lot of old Yorkshire and I rang him and I said, “Blake! That’s it! It needs all the old Yorkshire in it! Yorkshire-fy the German – localise it to where you live, Skipton,” and from then on, that was it. Oedipus was localised to Skipton. We did Oedipus during the foot-and-mouth scare – there were people burning vast pyres of cattle and people with bed and breakfasts topping themselves, so it was very, very relevant.

What about Tom Paulin’s Medea?

Tom sent me the script and we had a slot so we did it. And before Ted Hughes died he sent me his last play, Alcestis – it was his wish that it should have its premiere in the Calder Valley. We weren’t friends but I’d met him a couple of times and we wrote to each other – I still have the postcards he sent me. It was Susannah Clapp of the Observer, the critic, it was her who had the idea 10 years ago of the Brontës as a kind of adjunct from Chekhov’s Three Sisters and she passed the idea on to Blake. I found out about it by accident, said to Blake, “Is this something you want to do?” and he said, “Yes,” so I said, “Right. Get writing - autumn 2011.” That became We Are Three Sisters, the last production we did. (Pictured left, Nina Kristofferson as Medea, 2010)

Tom sent me the script and we had a slot so we did it. And before Ted Hughes died he sent me his last play, Alcestis – it was his wish that it should have its premiere in the Calder Valley. We weren’t friends but I’d met him a couple of times and we wrote to each other – I still have the postcards he sent me. It was Susannah Clapp of the Observer, the critic, it was her who had the idea 10 years ago of the Brontës as a kind of adjunct from Chekhov’s Three Sisters and she passed the idea on to Blake. I found out about it by accident, said to Blake, “Is this something you want to do?” and he said, “Yes,” so I said, “Right. Get writing - autumn 2011.” That became We Are Three Sisters, the last production we did. (Pictured left, Nina Kristofferson as Medea, 2010)

It's the language that really matters to you isn’t it?

It is. It’s like a great casserole of food. Wrapping your gob around great, wonderful - often rhyming - language is one of life's great pleasures to me.

I know you’ve done some television since forming Northern Broadsides, but have you appeared on stage in anything but your own productions since you started the company?

I played Hobson [in Hobson’s Choice by Harold Brighouse] last summer at the Sheffield Crucible, directed by Chris Luscombe and he is the first stage director I’ve worked with since I started the company. That was terrific because it’s a great part and a great play and Chris led a great team. It was a very happy experience and I also enjoyed it because of what I call the "corridor time" which means because you’re not directing and on duty for every scene you can sit outside and learn your lines or even do a bit of shopping or phone your accountant. In fact, I enjoyed it so much, I’ve already chosen the play I want us to do next January and I’ve asked someone else to direct it. There’s a lot of Shakespeare happening this year, what with Stratford and the Globe, so I thought next year we’d start off with a non-Shakespeare play, so we’re going to do Rutherford and Sons by Githa Sowerby. I’ll be acting in it but I won’t be directing.

Is it a relief to occasionally accept a job purely as an actor – be it on stage or television – and leave the responsibilities of directing to someone else?

It is although there’s nothing like the full-time occupation [of running a company]. It’s like football managers who say, “I want to run a football club, not be England manager because I want the day-to-day stuff.” It’s a very heady experience sometimes. It has the ability to take you to incredible heights and you can also go into the depths of despair – all that wonderful whirligig of emotion. But there’s nothing like it - it least it proves you’re alive.

Does it change your relationship though when you are the director and the actor in the play with the other actors?

No, because everybody knows what they’re coming into with me and the new people – we have a lot of people – if they don’t know, they do within five minutes. But it’s fun, I try to make everything fun. Sometimes you’ve got to drill stuff in – like lines. If someone says, “Barrie, I don’t understand these two lines,” I say, “Well it’s a rhyming couplet. Get the couplet and it will give you the sense,” and it always does. It’s that sort of poetic muscularity.

Lenny Henry said in an interview that you don’t sit around discussing psychology - you like to get on with the language.

Elizabethan and classical plays are delivered via their construction, not in spite of it. These plays were written before Freud and the camera. Often it’s about the music of the lines, the music of the rhythm, the music of the content.

When you start your rehearsal process, is there anything that is a constant? Anything that you feel you must adhere to, that runs through everything you have ever directed?

The insistence that no one hammers pronouns. That nobody hammers ands like they do on telly or observes commas – because they have been put in by other editors over the 400 years since he [Shakespeare] died - and all these plagues that abound within a lot of classical acting today. You know, this is my sword – well who bloody else’s would it be? This again is the music of construction and I try and drill this in. I’m not always successful, I have to say.

Do you think that's down to how actors are taught at drama school?

No, I think they teach them a lot more psychology at drama school now. When I hear young people now, when I take auditions, they all want to be Cleopatra instead of saying, “Right, this speech is made up of 14 rhyming couplets. Let’s see how we get there, via it, not in spite of it."

If Shakespeare tells you have to do something or look a certain way, then you have to do it

You don’t believe in the idea of “character”, do you?

Well, you have to acknowledge the 20th and 21st century. However, the word "character" grew up with the English novel when writers and characters in novels could play God. Now before that, it was roles to play and characteristics – I’m a great believer in characteristics. If Shakespeare tells you have to do something or look a certain way, then you have to do it. If you’re described as a “fanatical phantasime” as Don Armado in Love’s Labour’s Lost, then you have to be a fanatical phantasime. There’s no point in investigating what the character of a fanatical phantasime is. So it’s characteristics and there are often many more clues in a play than we give credit for – these ancient plays that had to have a spellbinding language and a spellbinding sense of theatre to be performed in big, vibrant public places.

But what happen when you're not directing - when you’re working on television or with Chris Luscombe, say? Do you still apply the same rules?

I try to. I keep quiet, if I’m not directing it because you have to. I’m a bit of a virgin on television but I always say to the director, “Look, tell me what to do, I’m in your hands.” I’m quite humble about that. But I try to apply those same rules that I ask for in the theatre to television and radio.

When did this first strike you – the fact that Elizabethan and classical plays weren’t bothered by internal characterisation?

It was a gradual process through directors like Terry Hands and Peter Hall, who I worked with a lot, and then Tony Harrison and going back to ancient times when the actors all wore masks so you had to write spellbinding language and that’s what’s missing today. I don’t mean everybody has to do Greek plays in masks, but that the attention grabbing was via language.

But obviously, when you are directing a production, you decide it’s going to have a certain shape, you’re going to set it in a certain time….

No, I don’t really mess about like that.

But you had three Ariels in your production of The Tempest.

At one point Ariel moves around and speaks three times to Trinculo and her voice comes from three separate places and I thought, “Well, why not have three Ariels?” so we did. I’ve often seen Caliban played by a black actor – that sort of Colonial idea – but I’ve never seen Ariel black and Ariel was trapped just as much Caliban was earlier on so I thought, “We’ll make Ariel black then and have three girls do it.” Of course they also played the goddesses so their parts were a little bit bigger and it worked very well indeed.

And Love’s Labour's Lost is set in the Thirties.

It is although I don’t bother with all the props that belong to that era at all because that can hang you – you’ve still got to talk about rapiers and stuff - so although the clothes are basically of that period, I don’t go all the way. Also, we’re the only touring company that goes to different shapes of venue nearly every single week so you can’t carry – and it’s never interested me to carry – the panoply of a setting. When we leave here in the round, we’ve got to be able to jump straight into a proscenium arch and then we’ve got to jump into traverse and then the next week we jump into something else and the production has to remain consistent so stuff gets in the way. But it’s part of the fun and it’s how we’ve worked for the past 20 years.

But why did you choose the put the cast of Love's Labour's Lost in 1930s costumes?

The designer suggested it and it fitted the production. It’s nice. It’s our 20th year so we’ve thrown some money at it – but for costumes for people to wear, not for settings.

Why did you choose Love’s Labour's Lost for the anniversary production?

Because other more well-known companies were doing the plays I wanted to do! But now I’ve took it to bed for a few months and I’m looking at it and working on it, I’m delighted with it. It’s a great box of verbal fireworks and I’m loving it.

I know you’ve got a few special things lined up for it.

I know you’ve got a few special things lined up for it.

Well, there’s a big cast for a start, 17 actors - although we get the least money of all the touring companies we always put the biggest casts on stage. There’s also one of the most famous scenes in Shakespeare, where a messenger comes on with the news that the princess is dead and I said to my producer, “Look, I don’t want this face to have been seen at all in the play before,” and then someone said, “Why don’t we ask Broadsiders who are not in this production to do one- and two-night stands and just come on as the messenger as a surprise. So we’ve got about 20 or so people all lined up to play the messenger. I mean, they’ll have to learn three lines and I’ll give them rehearsal so it won’t be a surprise to us but the audience will not have seen that face before during that evening. It’s going to be lovely. I’m hoping Lenny [Henry] is going to do a couple of shows. (Pictured above: Fine Time Fontayne, Rebecca Hutchinson and Barrie Rutter in rehearsals for Love's Labour's Lost. Photograph by Nobby Clark.)

I was going to ask you about Lenny Henry - but only briefly as his association with Northern Broadsides has already been well-documented - but I am interested in how he settled down to being part of a company, working with people who were by no means as famous as him, but highly skilled and far more experienced on stage.

It worked because he was so humble about the whole damn thing. He loved being in a room or in a corridor with other people learning lines and now of course, he’s at the National Theatre [in The Comedy of Errors]. He said to me – we had breakfast the other week – he said, “This is what I want to do.” He loves working with other people. I’m not saying he’s been lonely – and he’s not saying he’s been lonely – for the past 25 years but now he’s reached 50-odd he’s changing his life and this is partly the stuff that he wants to do.

What's happening after Love's Labour's Lost?

My colleague Conrad Nelson is directing the next big production, a version of The Government Inspector by Gogol adapted by Debbie McAndrew, utilising brass bands, and then we start Rutherford – director to be announced. I’ve already commissioned a play from Debbie McAndrew for 2014, the centenary of the World War One. I’ve called it An August Bank Holiday Lark which is a line from Larkin’s poem MCMX1V.

And lastly, as it is Northern Broadsides' 20th anniversary, can you identify any particular highlights?

[Big sigh.] Well, there’s been lots - performing our production of Richard III inside the Tower of London in 1994 - that was a bit of a high. The Creative Briton award. But to be honest, just the fact that Northern Broadsides has made it to 20 is a bit of a high in itself.

- Love’s Labour's Lost is the New Vic Theatre, Newcastle-under-Lyme unti 18 Feb and then at The Duke', Lancaster (21-25 Feb), The Viaduct, Halifax (29 Feb-10 Mar), Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough (12-17 Mar), Buxton Opera House (29-31 Mar), West Yorkshire Playhouse (3-14 Apr),The Lowry Salford (17-21 Apr) and York Theatre Royal (1-5 May)

- Northern Broadsides' website

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment