Interview: Errol Morris on making Tabloid | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Errol Morris on making Tabloid

Interview: Errol Morris on making Tabloid

The director enters the strange world of Joyce McKinney

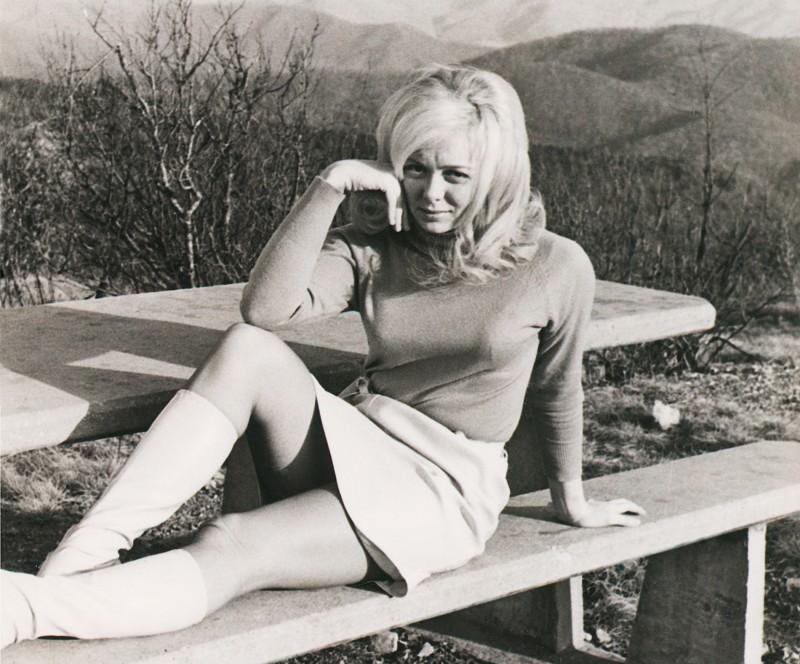

When the former Miss Wyoming, Joyce McKinney, walked towards UK Customs in 1977, she had a perfect tabloid story in her bag: handcuffs, a Smith and Wesson pistol, and a burning desire to rescue the love of her life from the Epsom Mormons.

In court, McKinney was the plucky, blonde all-American heroine, and on bail she became a sensation, upstaging Joan Collins at premieres and snogging Keith Moon. After skipping town to Canada with KJ, she dressed as a nun to tell her virtuous story in the Express. This compelled the Mirror to dig up photos of her time as a soft-porn model in San Francisco. It was “a love story, not a porn story”, she protests in Errol Morris’s new film, which is less about the affair than the vivacious enigma of McKinney herself.

She was lucky that it was Morris (pictured right) who came to her, though she clearly believes otherwise, serving a writ for damages in the US as he flew to London to deliver BAFTA’s prestigious David Lean Lecture and review his glittering career last Sunday. Only Frederick Wiseman has a higher reputation among American documentarians. His subject is humanity’s endemic self-deception and strangeness, whether interviewing the Vietnam War-era Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara in the Oscar-winning The Fog of War (2003), the self-amputating insurance scamsters and “swamp philosophers” of the small town of Vernon, Florida (1981), or the compulsive liar who almost sent an innocent man to the electric chair encouraged by the Dallas PD in The Thin Blue Line (1988), which helped reverse that injustice.

She was lucky that it was Morris (pictured right) who came to her, though she clearly believes otherwise, serving a writ for damages in the US as he flew to London to deliver BAFTA’s prestigious David Lean Lecture and review his glittering career last Sunday. Only Frederick Wiseman has a higher reputation among American documentarians. His subject is humanity’s endemic self-deception and strangeness, whether interviewing the Vietnam War-era Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara in the Oscar-winning The Fog of War (2003), the self-amputating insurance scamsters and “swamp philosophers” of the small town of Vernon, Florida (1981), or the compulsive liar who almost sent an innocent man to the electric chair encouraged by the Dallas PD in The Thin Blue Line (1988), which helped reverse that injustice.

On stage on Sunday, the 63-year-old was a ruminative raconteur and playful showman, exploring his philosophy in a slow, gravelly New York voice: “Two great mysteries concern me. What really happened… and a deeper mystery - what’s happening inside people’s heads… I don’t think we can know each other or ourselves.” A “contrarian”, he inverted documentary conventions from hand-held, fly-on-the-wall filming to shamelessly cinematic, staged scenes jaggedly recreating people’s perceptions of the truth. As an interviewer, this highly intelligent man has the grace and sense to listen to his subjects. That was how he “cracked a murder case with a camera” with The Thin Blue Line, and let McNamara, who others would have angrily put in the dock for Vietnam, muse he was a war criminal for his forgotten part in the US fire-bombing of Japan.

He holds the stage for two hours at the lecture and questions that follow, and when we meet the next day he rubs his face, tired, but still amused and enthusiastic about life’s absurdities. McKinney’s writ didn’t faze him. “I’m not really surprised,” he sighs. “I wish she hadn’t. I’m not the first person she’s ever sued. She’s extraordinarily litigious. I would insist that the film is actually a loving and respectful portrait of Joyce. Now she may feel otherwise. But… I like her. I think she’s an extraordinary romantic character.”

McKinney, in her sixties now, seems on the downward spiral of the story she spun around her one pure love, the hapless “Manacled Mormon”, 34 years ago. Where most of us think we’re the hero and heart of the tale as we go about our lives, McKinney made her real life as vivid and exotic as the stories she’d read. When her story-book romance with Anderson was interrupted by his vanishing to Surrey, she turned it into a true-crime thriller. She passionately believes the tale she’s created, regularly moving herself in Tabloid to laughter and tears.

“What is so strange about that interview,” Morris reflects, “is that she can be laughing and then crying within the space of seconds. The range of affect alone is remarkable. I’ve never seen anything quite like it. And it was clearly a performance. Not to say that it loses something as the result of that fact. She blurts out at one point in the interview, ‘Thank God for all those years of drama school,’ as if she herself is aware of this. It’s a performance and it’s real, which is what’s interesting.”

The fearless, spellbinding heroine who took the stand in London in 1977 was shaken when a tabloid circulation war over her story took it out of her control and made it sleazy, and when Kirk Anderson finally preferred the Mormons to her. Since then, she has become a victim, someone bad things happen to: being badly mauled by her dog (pictured left, McKinney today), fallen on by her horse, crashing her car. Does Morris feel he understands her?

The fearless, spellbinding heroine who took the stand in London in 1977 was shaken when a tabloid circulation war over her story took it out of her control and made it sleazy, and when Kirk Anderson finally preferred the Mormons to her. Since then, she has become a victim, someone bad things happen to: being badly mauled by her dog (pictured left, McKinney today), fallen on by her horse, crashing her car. Does Morris feel he understands her?

“No,” he says. “Not at all. This kind of deeply passionate romantic quest to nowhere, which has the character of a fable. When the British journalist says in the film [in the Seventies], ‘Do you realise, Joyce, that you’ve condemned yourself to a life of loneliness?’ and she agrees, I don’t know what to make of it. In the interview, Joyce mentioned this Theodore Dreiser short story she had read, Second Choice. It’s a peculiar story, about a woman who’s in love with a man, and it has these letters that he’s sent. And it’s clear from reading the letters that he doesn’t really love her. And he’s really never coming back. So you read this with a certain kind of horror. And she tells herself that she’s never going to settle for her second choice. She does. And you feel that she ends up like her mother in a loveless, featureless marriage. So Joyce tells me about the story, and said, ‘I resolved that that was never going to happen to me.’ And the irony, of course, is that what ended up happening to her may be worse.”

Tabloid includes footage from a film made in the early Eighties of McKinney reading from her unpublished autobiography (pictured right), written as if she is a fairy-tale princess destined to live alone, having lost her handsome prince.

Tabloid includes footage from a film made in the early Eighties of McKinney reading from her unpublished autobiography (pictured right), written as if she is a fairy-tale princess destined to live alone, having lost her handsome prince.

“When I look at that, I think, my God, do people script their lives then re-enact them? Is that how it works?” Morris ponders. “Maybe it is.”

Morris considers himself a journalist. Tabloid offers the highly entertaining reminiscences of ex-Fleet Street hacks Peter Tory (of the Express, who wrote about McKinney the saint because they bought her story) and the Mirror’s Kent Gavin (who dug up stories of her past as a soft-porn “whore”, because they didn’t). Only when Gavin laughs fondly of McKinney threatening to jump from a balcony does the downside of journalism devoted to the thrill of the chase, where the people involved are collateral, intrude. “She kept us all entertained in 1978,” ex-Express editor Derek Jameson sums McKinney up in a clip in Tabloid, when she resurfaces in 1984. In this colder, bigger world, her colourful fantasies were crushed.

Morris draws a line, though, between those days and the News International scandal. “The Milly Dowler story to me is not a tabloid crime, it’s just a crime,” he says. “And yes tabloid culture may have encouraged it, may even have caused it. If Joyce comes to the UK with handcuffs and chloroform - let’s assume that she did, at least with the intention of kidnapping Kirk Anderson, whether she did kidnap him or he came willingly - that’s different from parents who’ve lost a child, where if you ask me as a parent if there’s anything worse, there really isn’t. Part of what made that whole scandal so dark and depressing is that people really were victims. A daughter was murdered, the News of the World interfered with a police investigation, interfered with police evidence - violated any kind of journalistic ethics. Having said that, if Peter Tory tells you [of the “Manacled Mormon”], ‘I think it was ropes. But chains sounds better…’ it’s certainly not reporting per se. Journalism in pursuit of the truth doesn’t mean you have to arrive at it. It’s an elusive kind of thing, after all. But without the pursuit, it’s not journalism.”

Short documentary on The Thin Blue Line (incorrectly stating it won an Oscar)

The Thin Blue Line remains Morris’s most remarkable investigation, eliciting a taped near-confession from the real killer David Harris, and the revelation that a crucial witness first identified the “wrong” man, not the falsely accused Randall Adams, in a line-up (“The policeman pointed out the right one, and told me not to make that mistake again,” she blandly told Morris, in a chilling moment Dallas PD lawyers surely kept out of the film, recounted at his lecture).

“You can tell a very powerful kind of story about people’s avoidance of the truth, about people’s desire not to uncover it,” he says. “Those stories deeply fascinate me. The people who live in a strange miasma of their own devising. The clip that I showed from The Thin Blue Line at the lecture, which is [the false witness] Emily Miller fantasising about how she was a detective or the wife of a detective is a perfect example. Basically she’s the woman who fingered Randall Adams as the murderer - not alone, but a principal witness. And this is the scary part. We take solace, I think, in lying and in conspiracies - we think, oh, that person is lying, that person is trying to trick me intentionally. But often, people are true believers in what they say. No matter how absurd or false or preposterous this belief may be, they believe it.”

Morris himself seems to have lived a remarkably self-created life - pitching up at a series of top universities such as Princeton and Berkeley almost straight off the street, taking a variety of degrees and PhDs till they disappointed him and he moved on. He was a private investigator before he was a film-maker. Did that fulfil similar fantasies in him, albeit more rationally, to those Miller pursued?

It was my attempt to relive Psycho, on a personal level... it’s the desire actually to become part of that story

“Absolutely yes. I’m someone who really loves detective fiction and crime drama. The most obvious example I can give you is that I started interviewing murderers even before I became a private detective. First mass murderers in Northern California, when I was a student at Berkeley. And then I went back out to Wisconsin, where I had been an undergraduate and one of the most famous cases was Ed Gein, who was the basis for Psycho. This was an infamous case, there was a huge spread in Life about the Gein house of horrors, the human taxidermist, grave robber, mass murderer. And so I got to interview Gein.

“I decided that I would go up to Plainfield, Wisconsin, where Gein had come from,” Morris continues, “and eventually ended up living with Ed Gein’s neighbours. It was in many ways my attempt to relive Psycho, on a personal level. And Robert Bloch had based the story partly on fact. They had moved the highway away from the centre of town, and there was, not the Bates Motel, but the Plainfield Motel. And as I’m driving up [Route] 54 to Plainfield, it starts to rain, and the windshield wipers are going” - relish in Morris’s voice now as he remembers- “and I turn off the main highway. There are the lights of the Plainfield Motel. And I spent the night there. And there was a painting on the wall, and I moved it to see if there was a peephole. But it was not there. But yeah, it’s the desire actually to become part of that story.”

One of Morris’s least-seen films is A Brief History of Time (1991), about Stephen Hawking and his iconic science book, which Morris sees as a secret autobiography. If I knew Morris well enough, would I be able to construct an autobiography of him from the stories he’s told?

“I think you could actually. I am trying to figure out about people, maybe about myself, what makes me tick. It goes back to this whole question of beliefs and ideas. One of the things that attracts me to [British documentarian Adam] Curtis’s work is it’s an extended essay on the power of ideas and belief. I know that I’m different. It’s that world of fantasy, what’s inside of people, that animates their lives, it’s one of the things that draws me to Joyce. Perhaps I’m a creature very much like Joyce, with some infernal script I’m re-enacting.”

Morris only made so many documentaries because decades-long writer’s block frustrated him from creating his own stories. His films have been laborious substitute ways of doing so, wasting time which he tells me he regrets.

“One of my earliest memories,” he says, thinking further of the autobiographical elements lodged in those films, “is that somehow I would always be trapped inside myself. I’m very grateful now, because I couldn’t write for years, that I’m suddenly able to write books. But the idea of being trapped inside of yourself and unable to escape is a recurring image that endlessly fascinates me.”

“What a bizarre world we live in,” cinema’s private investigator concludes, still puzzled and glad this is so.

- Tabloid is on UK release

Watch the trailer for Tabloid

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Add comment