Rostropovich: The Genius of the Cello, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

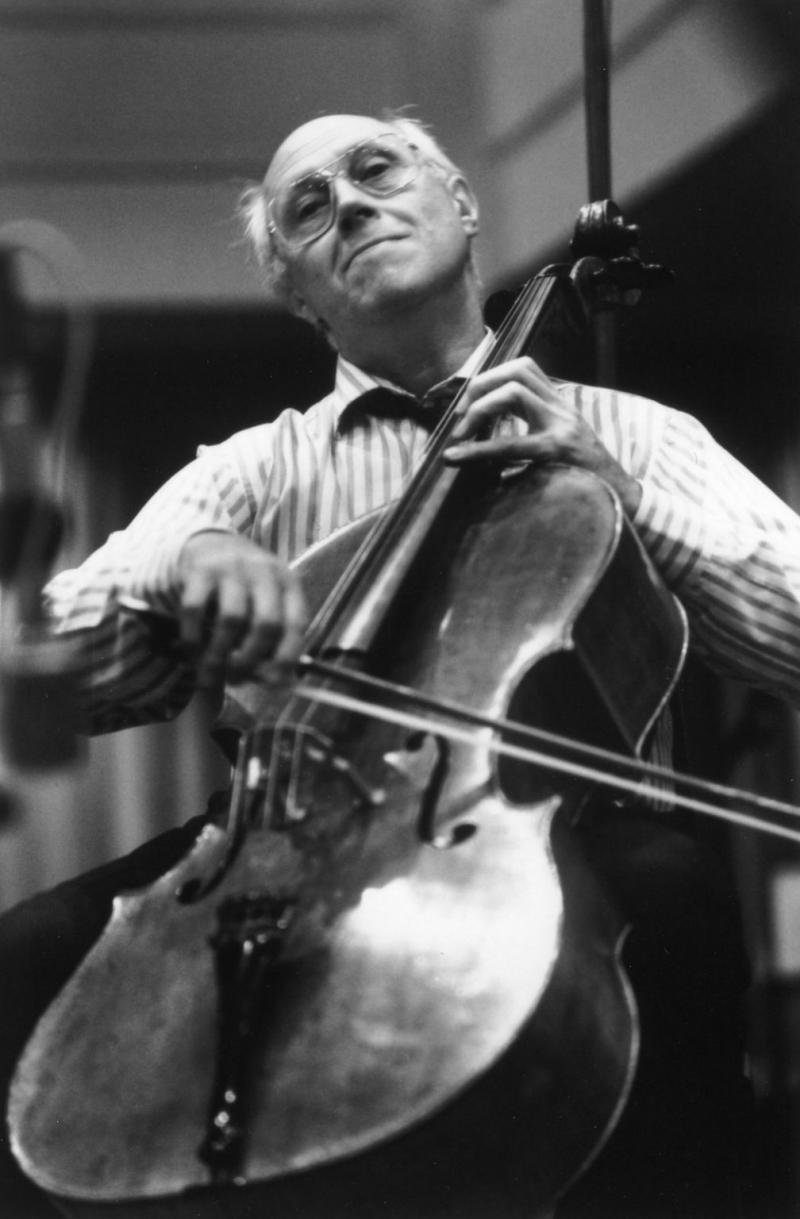

Rostropovich: The Genius of the Cello, BBC Four

Rostropovich: The Genius of the Cello, BBC Four

Life force incarnate: former cellist-pupils, friends and family react to his performances in John Bridcut's great documentary

How can even a generously proportioned documentary do justice to one of the musical world’s greatest life forces? John Bridcut knows what to do: make sure all your interviewees have a close personal association with your chosen giant in one of his many spheres of influence, then get cellist-disciples from Rostropovich’s Class 19 in the Moscow Conservatoire – here Moray Welsh, Natalia Gutman, Karine Georgian and Elizabeth Wilson - to watch and listen to their mentor talking and playing.

Even without that special dimension of on-the-spot reaction to recorded music-making – one which Bridcut cultivated so successfully in his film about Elgar – this would be a moving testament. How could you possibly make boring a life which included a whirlwind wooing of another great performer – the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, always good value in interviews - resulting in a 53-year marriage, the game-changing performance of Dvořák’s Cello Concerto on a Russian orchestra’s troubled visit to the Albert Hall in 1968, the long-term fallout from Rostropovich’s courageous defence of Solzhenitsyn and his crazy, tell-no-one arrival in Moscow without a visa to make a stand against the 1991 attempted putsch?

Well, I can think of documentary-makers, mentioning no names, who could make it hagiographical, over-sensational and more about them than their subject. Bridcut has always been motivated by what seems a selfless love for complicated greatness; Britten and Elgar have been fine candidates for his determination to set misconceptions straight. Rostropovich needed no such special pleading, even if it is of incidental interest to find out, say, about the surprisingly strict father who burned the lovingly decorated jeans brought back from the West for his daughters by their more indulgent mamma (Olga and Elena Rostropovich add character and flavour throughout).

Moray Welsh remembers arriving for a private lesson with wadges of cash... only to be told that the cost was one pence

As always with this director, though, the music’s the thing. Although Bridcut sidesteps the question of Rostropovich the conductor – this is purely about the most charismatic cellist of the 20th century – he is never afraid to use other musicians to let us see how genius actually operates. We get a masterclass from other cellists on how he made his instrument a voice, how he produced that continuous, breathing legato with fabulous bow changes. We feel we’re in the same room of the Moscow Conservatoire with him teaching, as the wonderful Liza Wilson – his superb biographer, and consultant on this programme – stands there bringing the archive footage back to life.

The great Natalia Gutman looks sheepish as she recalls how Rostropovich told her student self she played "like a policeman in a glass booth… you should weep, there’s nothing shameful about weeping to Rachmaninov’s music". Another student, we learn, a promising Armenian who played Locatelli with technical perfection, to the awe of the other students, gets presented with an invisible suitcase of crocodile skin, with gold buckles – "Take it, open it, what’s inside it? Nothing. That’s you. You haven’t got any ideas inside of you." Yet despite sometimes keeping his acolytes waiting for anything up to 10 hours, this man could be generosity itself. Moray Welsh remembers arriving for a private lesson with wadges of cash, having no idea what you pay the greatest cellist in the world, only to be told that the cost was one pence, which he was then obliged to produce.

Punctuating the documentary in true rondo style are Rostropovich’s relations with the three great composers who made him at peace with the idea of dying, "because then I meet these friends". It was news to me, from the testimony given by an orchestral musician, that Rostropovich actually changed swathes of Prokofiev’s towering Symphony-Concerto in rehearsal: “Sergey Sergeyevich, do you mind?” “Alright, good, I agree,” came the reply from the laconic composer. There’s moving elaboration of how Shostakovich would ask the junior cellist round and then ask him to sit in silence for up to an hour and a half – very hard for Slava, for whom “two minutes not opening my mouth feels like half a life”. And then Shostakovich would say, “Thank you, Mstislav Leopoldovich, life is much easier now.”

We see the cellist-interviewees respond in awe to a phenomenal film of Rostropovich’s playing at the world premiere of Shostakovich’s Second Cello Concerto. Even more remarkable is a coup which Bridcut saves for his grand finale: matching newly discovered archive film of Rostropovich alongside Britten conducting his Cello Symphony in Moscow with the already existing sound, and gathering those same cellists together in a viewing room to react. And what is virtually the final clip, of Rostropovich saying, “Friends, I love you,” is anything but baloney, as what's gone before has so richly proved.

Everyone who ever met him – and I was lucky enough to interview him on three occasions - knows how you’d get the three big kisses, the same stories that changed slightly each time. But his energy, the boundless devotion which led him to leap on a plane to Japan when he learned that a good friend, a sumo wrestler, had just lost a child, play Bach outside his house and fly back to England again, the phenomenal combination of cliff-edge intensity and perfect intonation in his playing: these amount to the real thing. I wept for days after his death every time I put on one of his recordings – the Schubert Arpeggione Sonata with Britten at the piano, as noted here, being perhaps the height of his perfection – and I wept quite a lot during this. Such a force of humanity demands no less.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Fabulous documentary! I would

I think the piece you mean

I think the piece you mean was Glazunov's Chant du Menestrel.

Stunning, heart stopping,

where can i find all of the