An encounter with John Richardson, Picasso's biographer who has died at 95 | reviews, news & interviews

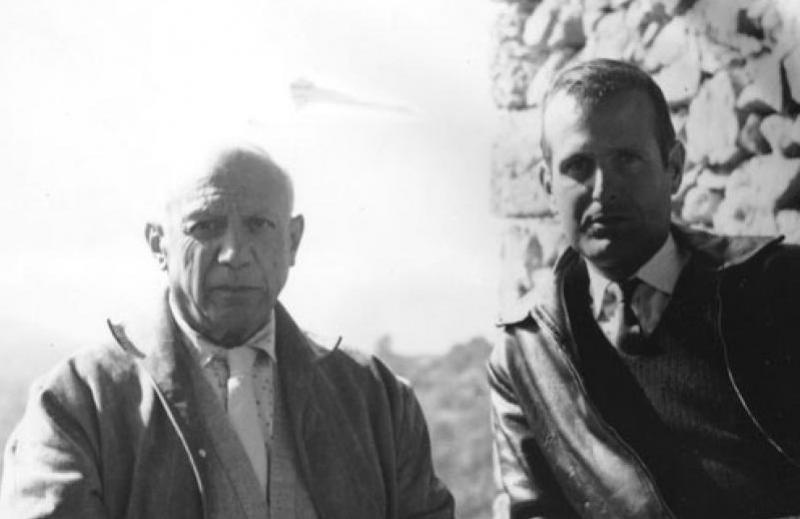

An encounter with John Richardson, Picasso's biographer who has died at 95

An encounter with John Richardson, Picasso's biographer who has died at 95

Picasso's definitive biographer recalls the artist he knew

When I interviewed John Richardson, who has died at the age of 95, he was edging through his definitive four-tome life of the minuscule giant of Cubism. Of the various breaks he took from the business of research and writing, one yielded The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a gossipy, elegant account of his own friendship with Picasso in the 1950s, when he lived in Provençal splendour with Douglas Cooper, then the owner of the finest collection of Cubist art in the world.

Richardson was taken up by Douglas Cooper in London after the war. The relationship was unofficially an open one, but Cooper was tyrannically jealous. But he was more jealous of Richardson’s connoisseurial talent. The end was nigh when Richardson identified some Légers as fakes, which Cooper had missed. Richardson escaped after a dozen years to Manhattan, where he became the head of Christies and the quintessentially wry Englishman in New York, where at 86 he remains.

A Life of Picasso began its long gestation in 1991 with the publication of The Prodigy, 1881-1906. Five years later came The Cubist Rebel, 1907-1916. The most recent volume to appear was The Triumphant Years, 1917-1932.

His total Picassian immersion is manifested not only in the biography but also in curatorial forays. His first was a nine-room retrospective in New York in 1962. In London he has curated shows at the Gagosian Gallery, including Picasso: The Mediterranean Years (1945-1962), which more or less covers his own period in the inner circle. Richardson reminisced about life in Provence with theartsdesk.

JASPER REES: When making Picasso’s acquaintance, did you feel at once privileged and aware that this would at some future date be useful to you?

JASPER REES: When making Picasso’s acquaintance, did you feel at once privileged and aware that this would at some future date be useful to you?

JOHN RICHARDSON: I don’t think I ever thought of my friendship with Picasso in terms of usefulness to me except in so far as I started by being a sort of groupie, and I had such a passion for his work and I think I had great understanding of his work from early on, and then little by little I realised that I was in a very good position to write about his work. I wanted originally to write a study of his portraits. Talking to Dora and to him, and realising how with the change in the mistress or the wife everything else changed with it and how that partner could be applied to his work. Now it’s a commonplace, people tend to think of his work in terms of his mistress, but in those days people didn’t think like that. But I came up with this view and this became a kind of vocation in my mind. It was something I felt well placed to do.

Did it necessitate befriending the mistresses?

No. Dora Maar was a neighbour and she spent half the year in Provence. Jacqueline was a whole different thing. I loved Dora but she was very difficult to get close to because she had this piety which she wore like armour and you had to watch your words with her. You said the wrong thing, she would get terribly angry, whereas Jacqueline was this girl from nowhere. I just felt she was the only person for him. She was consumed with love for him and would do anything for him. He told this story about his sister Conchita, when he swore that he would never ever paint again if her life was spared, and he did paint and she died, and this he only told to the women in his life, for some reason, I suppose as a sort of warning. And she clearly must have very early on felt that she was ready for it. Like all martyrs, she was blind to so much, blind to the damage he was doing to other members of the Picasso family.

He once sent you and Cooper off on an errand to inspect a notebook of his drawings in Dora Maar’s possession. They turn out to be intensely frank open-leg nude sketches. Was that just wanton cruelty?

Having been this surrealist moll, she turned into this very pious woman and to see these detailed drawings of her ass or whatever it was… it was so typical of Picasso as a control freak that she was put through this ordeal. My feelings were very mixed. I was very very fond of her. I loved her. She was so clever and so unlike anybody else. So I felt for her, but on the other hand I was fascinated to be part of this little drama. It made one understand so much about their relationship and about Picasso’s character. Human feelings were engaged very much on her side but other feelings – what an amazing situation.

It’s as if she is being crucified.

It’s as if she is being crucified.

I think Picasso was setting her up for a situation which would hurt her very deeply. We didn’t know what this was about until we saw the sketch book. Douglas, who was not the most sensitive person in the world, was probably more than anything else thrilled to see this unpublished sketchbook and I think dismissed Dora’s shame as a “silly woman”, after she posed for the drawings. Also Douglas wanted to do a facsimile edition and realised we’d been sent on a fool’s errand. There was no way these drawings could be published.

The first two volumes of your biography dealt with the period long before your own period. Did that change with volume three?

I knew quite a lot of the people that were around. I knew Cocteau well, Etienne de Beaumont, all these people who become very crucial in the early Twenties I knew reasonably well. Although I was born in 1924, I knew more and more of the people as time goes on. But I didn’t meet Picasso till 1949. However, having known him well in the latter part of his life has been an enormous help writing about him earlier on. I am amazed by the number of people who say, “He must have been the most awful cad". My experience was he was anything but. He was a man of incredible generosity, not only with his time but with himself. This view that has been put around by pseudo-feminists - Arianna Stassinopoulos knowing absolutely nothing about him at all decided to cast him as a villain - and this perception has prevailed. One of the problems is that whatever you say about him, the reverse is also true. He was a misogynist, but absolutely adored women. He was stingy to his family but also incredibly generous. It’s no good writing about Picasso if you don’t take in the paradox of his character.

Picasso had absolutely no time for art critics. He also didn’t like his private life being unveiled. I wouldn’t think he’d like my great project at all

Did you have to behave with Picasso?

With Picasso I felt completely at ease. He put you at ease, especially the men. Women had a different ride, especially if they were young and attractive. But somehow he had this very Spanish, almost Arab thing for his men friends - the group that meets in the café and doesn’t bother to go home. He was brought up in this Andalusian pattern of life and his men friends were very crucial to him. He could discuss everything, he was very relaxed, no arrogance or pretension, and he did have this extraordinary sweetness which he is not always given credit for and generosity, and very very very funny.

What was his company like?

Obviously there were certain subjects you didn’t touch on. I once published this piece in the Observer, which was taken over by the French version of Reader’s Digest. When Picasso moved to La Californie he asked Braque to come and share it with him and use it as a studio. Braque turned him down and always went to stay with his dealer. Picasso was upset that I had published this thing which put him, he felt, in an invidious position of being rejected by his oldest friend. I am glad I didn’t have it out with him, but Jacqueline told me.

What interest did he display in you and Cooper as a couple?

He was a cannibal. He needed people who understood his work, loved his work, respected him, desperately, because that’s where he’d get his energy from. After a day with Picasso, where there wouldn’t be any stress of any kind, you suffered from total nervous exhaustion. You felt that he had taken every last atom of feeling out of you, and then he would go off in his studio at midnight and work all night at the age of 80 on your energy and love. So whoever you were, if he had taken a shine to you or he sensed that you were susceptible to this treatment, then he was like Dracula. He drained your last drop. Which of course was very gratifying, you felt you’d contributed something.

Douglas reminded him a bit of Diaghilev. I think he liked having sort of buffoons around, people who would make him laugh and at the same time be the butt of his barbs. Douglas did after have the best private collection of his Cubist work anywhere. Picasso loved coming to the house and seeing it in the context of the Braques and the Juan Gris and the Légers.

Douglas reminded him a bit of Diaghilev. I think he liked having sort of buffoons around, people who would make him laugh and at the same time be the butt of his barbs. Douglas did after have the best private collection of his Cubist work anywhere. Picasso loved coming to the house and seeing it in the context of the Braques and the Juan Gris and the Légers.

Did he value scholarship?

He had absolutely no time for art critics. He liked cataloguers. He liked his work to be published. The only piece of art criticism I ever heard him praise was Jean Genet’s piece on Giacometti. He also didn’t like his private life being unveiled. That’s why he was horrified and furious with Françoise Gilot’s book. He did everything he could to try and stop it. I wouldn’t think he’d like my great project at all. That’s why Douglas got thrown out, for rather an untypical thing: he was speaking of the illegitimate children when he said, “Why don’t you recognise your sons by Françoise?” That’s always been a mystery. He never made a will. As he always said, if he ever made a will he felt he’d die the following day. After his death the illegitimate children had to sue to get recognised by the estate.

Cooper was expelled for daring to imply that Picasso would one day die?

By saying that, in Picasso’s mind that translated as, “You’re going to die, and if you don’t recognise your illegitimate kids, they’re not going to get anything. But this is all predicated on your death.”

Was the expulsion total?

Oh, total. That’s the one thing I don’t understand about Douglas. He must have known that one of Picasso’s oldest friends since the Twenties tried to do this and was thrown out. Either he felt that he was different and totally miscalculated or it was self-destructiveness, which was very typical of Douglas: the one person he adored in the world and revered he would [offend], as he had offended virtually everybody else in his life.

How did it affect him?

I would think enormously. Picasso died not long after. Then of course there was a show of his late work at Avignon and Douglas wrote this disgusting letter to Connaissance des Arts, saying he took issue with whoever had written this piece and thought he had as much right as anybody to grade Picasso’s work and he thought this was daubs done by a senile old man in the antechamber of death, which hurt Jacqueline enormously and hurt Douglas more than anyone else. He came out of it seeming to be treacherous and stupid and cruel.

Was Cooper a father figure for you?

It’s very difficult to be detached about one’s own circumstances but I suppose he was very much a father figure and a mother figure too. I think that he had strong paternal feelings. In some ways we were so well matched. My passion for Picasso fitted in to Douglas’s good side. He was a marvellous teacher. He loved having pupils and was very good and generous at imparting knowledge until the moment when he realised that whoever he was teaching was becoming a competitor or knew too much, which is really the plot of my book. I think it came to a head after eight years or so. In my case it was a cumulative process of learning. I started off and wouldn’t have dared open my mouth saying that this was fake or authentic, but by living with these paintings my eye became sharpened and educated but also in those days I had very little self-assurance and I think it took a lot of time to get the strength of mind, especially given Douglas’s enormously powerful personality, to come out and say something like that.

The seeds of the end of the relationship were planted right at the beginning.

I suppose, yes. I think I had been kept down so much for ten years. I tried to be very careful not to sound whiny. I was pretty badly treated and swindled. Really he did terrible things. I had dinner with somebody who was a very close friend of Douglas’s who said, “You got him absolutely bang on. I could hear him and see him.” I don’t think it’s an unfair portrait. Here is this man who was so brilliant and had so much to offer and it all came to nothing.

What would Cooper have said about your memoir?

[Pause] I think he would have been outraged and furious. He had a very short fuse. After he’d thought about it a bit maybe he’d have seen the truth of it. I think he had very little perception about himself. He was a mass of Achilles heels and I probably unintentionally put my finger on far more of them than I would have intended.

In your memoir you wrote with some frankness about sex. How difficult was that?

Quite a difficult decision. I’ve never made any secret of my orientation and I felt that if I was going to write about Douglas I had to say as much as was needed about his and my sexual orientation to make sense of the book. If I hadn’t come clean about our sex lives, the book wouldn’t have made any sense at all. I wanted to face up to it, to be honest about it, without going into gory details. I had written an account of an extremely comical row we had in Paris once, and I cut it out because I thought it was too embarrassing to me.

It’s clear that your relationship wasn’t based on sexual attraction from your point of view.

No. We’re talking right from the beginning there were the seeds of ultimate disaster in the relationship. And that was a problem.

New York was a liberation for you?

It was indeed. And thank God I did it, because my life took off then, not just sexually but in every other way. I became Christie’s representative in the US and started writing quite a bit and I felt fulfilled. Douglas was such a control freak. To some extent I learnt everything I knew from Douglas, or rather everything Douglas knew, and then it was up to me to learn things from my own perception, and I was well out of it.

How jealous was Cooper?

How jealous was Cooper?

Very. He was insanely jealous and possessive. It somehow was made very difficult for me to stray. Occasionally I did, thank God. The relationship at first was based on honesty. “Everything’s fine, just tell me, we should keep each other …” Originally I said to Douglas, “I am by nature promiscuous, don’t be surprised if I wander off.” “No, it doesn’t matter so long as you tell me.” Of course the first time I told him… this was the bit I cut out of the book when there were shrieks and screams and suitcases thrown out of hotel windows and chases down the streets. I realised that one couldn’t be frank with him.

Did he stray?

I hope he did. I think when he went off to America I’m sure he did. That was fine with me. The problem with Douglas is he was very uxorious.

Were you for several years aware that an endgame would have to come about, and were you surprised by the bitterness?

It never occurred to me that somebody I had lived with and trusted and been very close to would do such monstrous things. It was a terrible shock, but then the subsequent manifestations of this weren’t so much of a shock. I was always prepared for them. For some time I felt, I am going to have to get out of this thing. I’d bore friends - should I/shouldn’t I? I had clearly been extremely unhappy for a lot of the time, although in many ways it was marvellous – the house, the collection, the friends, the rapport with Picasso. But at the same time I felt caged. I didn’t feel so much kept because I ran the house, a lot of that was my doing, I had a little bit of money, I could buy my own clothes, and I was earning a living. It seemed to me only right that he was older and richer and I was younger and poorer. It seemed to me as so often in relationships when one gets older one pays for people or tries to help people out. But that wasn’t a problem. The problem was being stifled, being caged, being bossed around. I was a person in my own right, I had views, I had something to contribute, I started buying things, I went off and wrote a whole lot of things about Braque which had nothing to do with Douglas. And I think this is when some ill feeling started to build up on both sides. It became clear that to save myself I should get the hell out as soon as I could. Picasso and Jacqueline said, “For God’s sake stay on, because when you’re away the place is so boring, Douglas is in a bad temper.”

Was Picasso aware that you were in a spot?

Oh yes, Picasso was so perceptive, and also had seen it all before. He was always comparing Douglas and me to Diaghilev and Massin. Picasso tended to be always on the side of the victim of the jealousy. But he saw everything in terms of a high comedy. He saw it as a farcical situation. He liked homosexuals because they were susceptible to his magic, and he could get a lot out in the way of love and respect and understanding. He tended to regard homosexuality with considerable humour. He had a Balzacian view of life as a kind of comedy.

Did your friendship with him always assume the shape of a relationship between an artist and an acolyte on bended knee?

He made life so easy. He was so unlike what you expect a great genius to be like. He was a friend and a lot of the time we were on the bed together or having lunch in a bistro. You couldn’t forget who he was because the imagination and the brilliance shone through all the time. It wasn’t a constant firework display but every so often the fireworks would go off and he’d say something or make some observation which was so Picassian and mind-opening. I knew Matisse a little bit but it was so unlike being with Matisse. You were very conscious that you were in the presence of a very great man, a very wise man who talked almost in periods. There you really were in the presence of greatness. Whereas Picasso was much more easy-going and warm and physical. He gave you huge hugs, regardless of whether you were male or female, young or old; he would always stroke you.

What would he have thought of the magnum opus?

I think he would have hated it because the only biography which he thoroughly approved was by a woman called Antonina Vallentin, who was a scrupulous, formal old lady who wrote an impeccable, boring book that didn’t delve into anything. Roland Penrose was such a devotee of Picasso that he managed to write a book with no shadows in it. I’ve put the shadows in.

But the fact that he would have hated it is not on your conscience?

Not in the least.

Is he safest with you, given that there would always be a big book?

I think he is much safer with me because I loved the man, I love the work, I have no illusions about his character, I see him as a total paradox. It’s always important to try and keep the reverse in mind.

'Picasso is painting' filmed by Henri-Georges Clouzot

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Comments

...

Richardson's portrayal of

Wilde had Richard Ellmann,