After Life, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

After Life, Barbican

After Life, Barbican

Bravely, beautifully banal new opera about one's last memory

Sunday, 16 May 2010

'After Life': Michel van der Aa's multimedia opera asks the big questions about life and death

"We need to inform you officially. Mr Walter, you died yesterday. I’m sorry for your loss." It comes as no great surprise to learn that Michel van der Aa’s opera After Life is based on a Japanese film. The Borgesian hyper-real scenario, the no-place location and meditative pacing all point, or rather - rejecting anything so crass - bow respectfully to their original source.

Adopting the premise of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s film of the same name, Van der Aa has created a multimedia opera that both asks and answers the question: if you could take only one memory with you after death, what would it be?

While this may sound like the unpromising beginning to a couple of hours of existential meanderings, the result is bravely – and beautifully – banal. A mop is sprawled languidly across an ethnic-print sofa, cosying up to an aged radio; faux-Chippendale chairs jostle for a place with filing cabinets and what looks like a rabbit hutch, and a stuffed dog sits companionably with a standard lamp: welcome to the afterlife, Van der Aa-style.

Rejecting a minimalist approach either to staging or philosophy, the composer fills his opera (and its stage) with the physical stuff of life, the furniture and debris of existence. It is from these unprepossessing objects that the inhabitants of his otherworldly holding room must recreate their memory of choice, preserving it on celluloid to take onwards with them into eternity, assisted by three uniformed officials.

As a student of Louis Andriessen, and trained not only in composition but film-directing and sound-recording, Van der Aa’s trademark is his integration of multimedia elements into his work. Filmed images interact with live action, recorded sound with live music; a better symbol of After Life’s subject matter of the relationship between memory and the lived moment could not be found. This synergy of theme and process is key to the opera’s elegant success – allowing it to enact its own philosophy without the need for either polemic or parable.

Two large screens fill the back of the stage, supplementing the onstage action with a fragmented series of recorded monologues. Four real-life spoken stories are added to the fictional sung ones, adding yet another turn to the narrative screw. In the event it is these true stories whose directness really captures the heart; a middle-aged man recalls his grandfather, an Afrikaner woman expresses her guilt at abandoning her country, and a Second World War refugee from Holland recounts her first conscious sight of her homeland. Most inspired however is the choice of a hilariously self-possessed small boy whose significant memories all involve family pets. Or death. Or, in one gloriously matter-of-fact case, both.

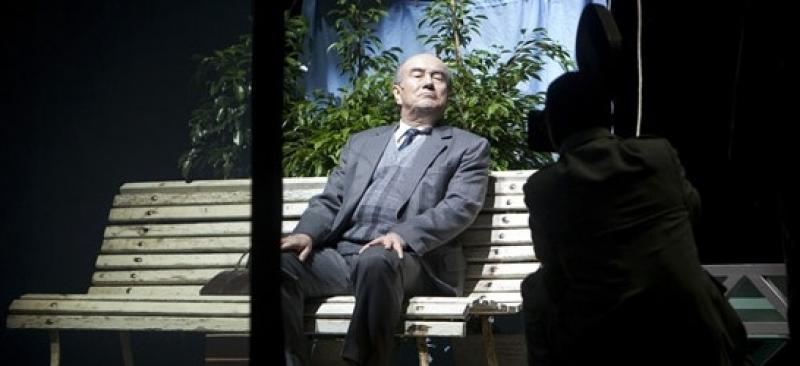

The cast of the much-lauded 2006 world premiere production were all back for this revised UK premiere. Roderick Williams can be relied upon to make expressive sense of even the most bizarre material (as his efforts in Kaija Saariaho’s L’Amour de loin last season at ENO testify), and here, given the platform of a genuinely intelligent text, his English lyricism was at its best. The combination of gravity and youthful energy that he possesses worked well for the figure of conflicted official Aiden, and his vocal control rendered implausibly smooth even the most aggressively disjunct of Van der Aa’s lines. He is strongly supported by Yvette Bonner as his enamoured co-worker Sarah, but I was less convinced by Claron McFadden as the Chief. Her famously flexible soprano voice – she performs in styles encompassing jazz and baroque – here sounded a little woolly and unfocused in the lower registers, though redeemed itself in the undeniable precision of the many vertiginous moments. Among the visitors it was Richard Suart’s Mr Walter who really compelled one's attention, delivering a beautifully understated performance as the man contemplating, and ultimately managing to celebrate, his unextraordinary "so-so life".

It seems odd to set aside discussion of the music itself for so long, yet in many ways this element is subordinate within Van der Aa’s work, the flitting black-clad theatrical minion ensuring that the collective elements of the drama fall unobstrusively into place. This is not music that demands attention, but is rather lovely for all that. Glancing at conventional tonality out of the corner of one eye, it is as though a classical symphonic score has strayed into a hall of mirrors; the arpeggios and key structures are all present but unexpectedly warped and distorted in form, living moment to moment rather than gaining any real horizontal momentum. Although used for the most part as a single textural unit, the orchestra (the regimentally precise ASKO|Schonberg Ensemble under the direction of Otto Tausk) occasionally gives way to a dominant instrumental texture: a harpsichord - astonishingly fragile in this contemporary context - a clamouring horn. And always in the background the pluck and hiss of electronic noises, the gentle reminder of the music to be found in such sound.

At its 2006 premiere in Holland After Life was performed to a capacity crowd, which included (among others) Queen Beatrix. The notion of our own Queen attending at the British equivalent is laughable for its sheer absurdity – a reminder of the rather different national context that has shaped and nurtured Van der Aa and his Dutch contemporaries. The Barbican’s biennial Present Voices series is always a timely look beyond our own backyard (and that of America) and, with a new work by Hans Werner Henze also on offer this season, Euroscepticism may be the order of the day in our politics but not – thank goodness – in our music-making.

- Check out the rest of the Barbican 2010 season

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment