LSO, Rattle, Barbican review - a glimpse into Bruckner’s workshop | reviews, news & interviews

LSO, Rattle, Barbican review - a glimpse into Bruckner’s workshop

LSO, Rattle, Barbican review - a glimpse into Bruckner’s workshop

A compelling case made for each version of the 'Romantic' Symphony

For most Bruckner fans, the multiple editions and revisions of his symphonies are a problem. But Simon Rattle sees it differently; for him every edition offers more music to explore.

The nominal reason for this concert was to premiere a new edition of the symphony, by the German conductor and scholar Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs (Anton Bruckner Urtext Gestamtausgabe, Vienna 2021). The Fourth Symphony exists in three different versions, of which the second is the most often performed. But the second version itself evolved through several variants between 1876 and 1881, most significantly by the replacement of the scherzo with an entirely new movement and the finale by a movement based on the same themes but radically different. Cohrs has created an edition that allows each of these different variants to be performed, through the judicious observation of various cuts and ossias, all marked into the score. Rattle’s programme was designed to perform as much of the edition as was possible in one go, hence the “discarded” movements in the first half.  The complete performance in the second half even included a transition passage that has never before been published, and possibly never performed. If all this sounds nerdy, it is, but Bruckner enthusiasts tend to be obsessive enough to follow along. Rumour has it that a recording of the programme is planned. No microphones were out this evening however: let’s hope they do it at the acoustically superior Cologne Philharmonie, where they are giving the same programme next week.

The complete performance in the second half even included a transition passage that has never before been published, and possibly never performed. If all this sounds nerdy, it is, but Bruckner enthusiasts tend to be obsessive enough to follow along. Rumour has it that a recording of the programme is planned. No microphones were out this evening however: let’s hope they do it at the acoustically superior Cologne Philharmonie, where they are giving the same programme next week.

The LSO was arranged on the Barbican stage to give full sonic impact. The basses were lined up along the top tier, projecting so well we could hear the buzz of their strings. The horns sat behind the second violins stage left, without risers, which was frustrating as they were the stars of the show and were all but invisible. The trumpeters played narrow-bore German trumpets, unusual for this orchestra, but certainly appropriate for Bruckner.

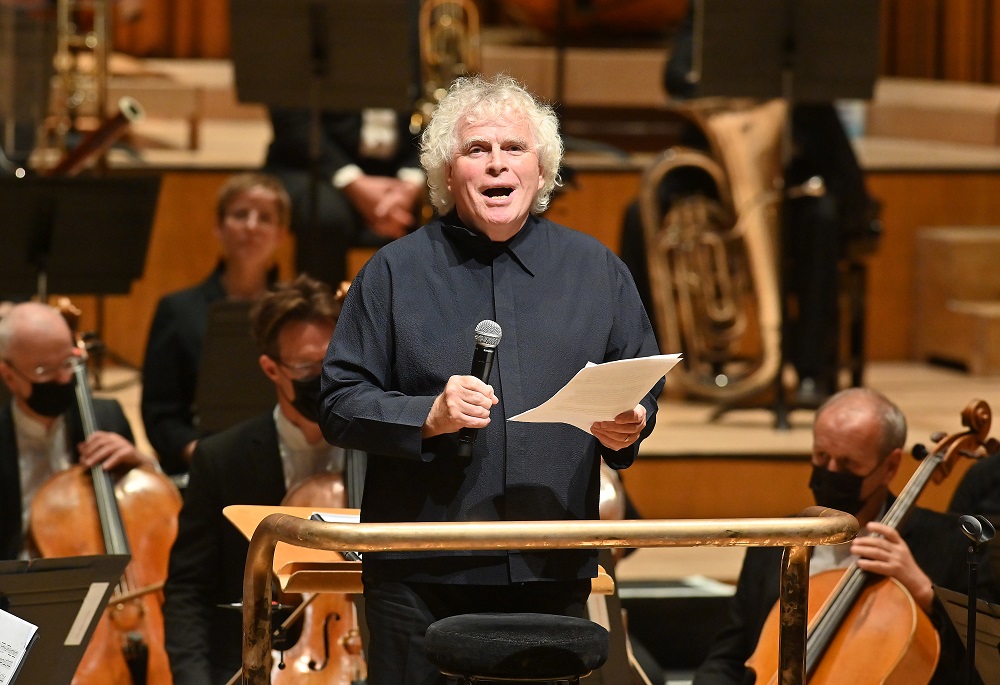

The discarded Scherzo itself exists in two different versions, of which this was the latter (1876). It is a pleasant, if conceptually limited movement, based on the alternation between solo horn figures (the submerged, but thankfully audible, Timothy Jones) and scurrying string flourishes. Rattle seemed to treat this music with delicacy, as if it were a fragile, ancient object. And, in fact, the simpler textures here probably warrant such an approach. The contrast was stark between this and the later Scherzo in the second half, but the greater sophistication and drama of the latter was exaggerated by Rattle’s cautious treatment here.  The earlier Finale, known as the “Volksfest” finale, for a folksy dance episode mid-way though, is a radical departure for Bruckner. It opens with a chromatically descending sequence it the strings, a device you wouldn’t associate with him. But Rattle’s programme was cunning here: having heard the Volksfest in the first half, the number of chromatically descending lines in the first movement became clear after the interval. In a brief address at the start, Rattle pointed out that the original finale was written in a single tempo, another radical departure. Rattle maintained that tempo, or stayed close to it, throughout, and showed how it could work. He was rigorous, but without being rigid, still shaping the phrases, while always with an ear for the relations between them.

The earlier Finale, known as the “Volksfest” finale, for a folksy dance episode mid-way though, is a radical departure for Bruckner. It opens with a chromatically descending sequence it the strings, a device you wouldn’t associate with him. But Rattle’s programme was cunning here: having heard the Volksfest in the first half, the number of chromatically descending lines in the first movement became clear after the interval. In a brief address at the start, Rattle pointed out that the original finale was written in a single tempo, another radical departure. Rattle maintained that tempo, or stayed close to it, throughout, and showed how it could work. He was rigorous, but without being rigid, still shaping the phrases, while always with an ear for the relations between them.

The lesson of the single-tempo finale informed much of Rattle’s reading of the full symphony in the second half (now conducting without a score, an impressive feat for the premiere of a new edition). Throughout this performance, of what was billed as the 1881 revision, tempos were carefully calibrated and chosen with clear intent. In the first movement, climaxes were often fast and driven, and where always thrilling. Build-ups achieved their effect through a growing sense of relentlessness and inevitability. In the quieter passages, Rattle was able to rely on tonal stability and lustre of the orchestra, especially of the woodwinds, but without ever lingering.  Particularly impressive was the interplay between the solo horn and the woodwind counterpoints, the flute in the first movement recapitulation, the clarinet in the scherzo, always carefully balanced. In the second movement, Rattle took Bruckner at his word, and kept everything Andante. Here, the climaxes were held back to the main tempo, limiting their breadth and scope. The Scherzo blazed with a fiery intensity. The punchy accents from the brass propelled the music and, again, the sheer discipline of the brisk tempos added to the music’s elemental power. One quirk here, and it is a Rattle trait: at the start of the Trio, he took the tempo right down, playing the woodwind entry absurdly slowly before gradually returning to speed with the strings’ response. An annoying affectation.

Particularly impressive was the interplay between the solo horn and the woodwind counterpoints, the flute in the first movement recapitulation, the clarinet in the scherzo, always carefully balanced. In the second movement, Rattle took Bruckner at his word, and kept everything Andante. Here, the climaxes were held back to the main tempo, limiting their breadth and scope. The Scherzo blazed with a fiery intensity. The punchy accents from the brass propelled the music and, again, the sheer discipline of the brisk tempos added to the music’s elemental power. One quirk here, and it is a Rattle trait: at the start of the Trio, he took the tempo right down, playing the woodwind entry absurdly slowly before gradually returning to speed with the strings’ response. An annoying affectation.

No such concerns in the Finale. Again, Rattle was keen to show how much more sophisticated this movement was than its predecessor, but also that the simpler tempo relations of the earlier version gave pointers to the structure. The tempos and textures felt unusually contrasted. The dark tone of the lower brass was ideal for the main theme, but the strings were always able to balance them in the climaxes. In the quietest passages, Rattle took the string tone down to a whisper, the players showing exceptional evenness and control. That new transition felt clumsy and abrupt—not even Rattle could work his magic on it. Never mind. Otherwise, this final movement was a triumph, driven inexorably to its glorious conclusion by an ever-engaged and ever-enthusiastic Rattle. This concert might have been structured like a history lesson, but everything here was compelling, thanks to the committed playing of the LSO and to Rattle’s passionate intensity.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Add comment