Gail Kubik: Symphony Concertante, Gerald McBoing Boing Boston Modern Orchestra Project/Gil Rose (BMOP Sound)

Gail Kubik (1914-1984) should really be remembered for writing the score to William Wyler’s 1955 noir The Desperate Hours, but Paramount decided that Kubik’s score was too modern and scrapped most of it. An intriguing, under-appreciated 20th century American composer and teacher, Kubik’s influences are brazenly displayed in the pieces collected here. His 1959 Divertimento No. 1 is heavily indebted to Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks, even down to the prominent use of a Bach quote. Copland’s Short Symphony is also lurking in the shadows. No matter: this five-movement work hangs together well and is brilliantly scored for a 13-piece ensemble, Kubik’s breezy energy instantly appealing. The Divertimento No. 2, this time featuring just eight players, offers more of the same, the Stravinskian parallels even stronger. These are unassumingly marvellous works, Gil Rose’s Boston Modern Orchestra Project making light of the metrical challenges. More ambitious is the Symphony Concertante for Trumpet, Viola, Piano and Orchestra, an imaginative recasting of a 1949 film score. It’s full of intriguing moments, my favourite being the extended muted trumpet solo which opens the slow movement. Soloists Vivian Choi (piano), Terry Everson (trumpet) and Jing Peng (viola) relish the technical challenges, and after the finale splutters to an abrupt halt you’ll feel compelled to listen again.

The one Kubik work you might have encountered is his score for an Oscar-winning 1950 animated adaptation of Dr Seuss’s Gerald McBoing Boing, a short that I dimly remember popping up occasionally in BBC schedules in the 1970s and 80s. In Kubik’s words, “the usual cartoon-making procedures were reversed: the score was composed first; the music served as a blueprint for animation…” Watch it on YouTube; it’s brilliant, and the music stands up well as a concert work. Here, Frank Kelley’s narration is almost as good as Marvin Miller’s in the original, Seuss’s tale of a child who can only communicate in sound effects accompanied by dazzlingly inventive music. You really need to hear this percussion-rich piece, and you’ll cheer when Gerald eventually finds success as a foley artist. An offbeat treat, superbly played and very well-annotated.

Shostakovich: Jazz & Variety Singapore Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Litton (BIS)

Shostakovich: Jazz & Variety Singapore Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Litton (BIS)

There’s variety aplenty here, but no actual jazz, the term loosely applied in Soviet Russia to describe light music of Western origin. One’s curious to know exactly what Shostakovich was able to listen to in the 1920s and early 1930s, and the delightful, pungent Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 1 from 1934 always reminds me of Kurt Weill’s Kleine Dreigroschenmusik. I always judge recorded performances by the quality of the Hawaiian guitar soloist in the deadpan foxtrot which closes the work. Gennady Rozhdestvensky’s stridently-balanced Melodiya disc is the one to have, but this new one from Andrew Litton and the Singapore Symphony Orchestra is a lot of fun, the guitarist suitably sleazy and partnered by a characterful trombonist. Litton directs from the piano, his tight, deadpan playing exactly what the work needs. What was previously (and incorrectly) labelled as Shostakovich’s Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2 (now the Suite for Variety Orchestra) is also included here, its eight numbers drawn mostly from film scores and assembled in the late 1950s. The playing here is superb, with exuberant clarinets in the “Dance No. 1” – listen out too for the delicious trumpet harmonies at 1’30”. None of it is top-drawer Shostakovich, but it’s effortlessly enjoyable.

The 1930 full-length ballet The Age of Gold is worth investigating, its plot following the adventures of a Soviet football team in the decadent West. Here we get the composer’s own suite. It’s not all froth; there’s plenty of bite in the ballet’s introduction and the impassioned ten-minute “Adagio” is one of Shostakovich’s great slow movements. It’s terrific here, the Singapore strings as impassioned as any, the crucial wind and brass solos flawless. A suite from 1935’s The Limpid Stream recycles the Jazz Suite’s opening waltz and ends with a throwaway pizzicato number. Litton adds as an encore Shostakovich’s Tahiti Trot, an arrangement of Youmans’ “Tea for Two” written for a bet and completed, apparently, in just 45 minutes. Litton’s rhythmic flexibility borders on indulgence but he gets away with it, just. A fun disc, beautifully performed and recorded. Good cover art too.

Gayle Young: As Trees Grow Xenia Pestova Bennett (piano), Ed Bennett (electronics) (Farpoint Recordings)

Gayle Young: As Trees Grow Xenia Pestova Bennett (piano), Ed Bennett (electronics) (Farpoint Recordings)

Start with Forest Ephemerals, one of Canadian composer Gayle Young’s "text pieces", here “based on descriptive prose to be pronounced silently as the music is played”. Listen carefully and the piano’s rhythms really do suggest speech, in this instance Young’s descriptions of spring wildflowers. There are allusions to Charles Ives’s Concord Sonata, and repeated phrases suggest Young emphasising a point or descriptive phrase, the final “Perennial Ephemerals” section halting abruptly as if she’s wandered off to look at something else. The spaces around the notes convey so much; this recording has so much body and immediacy. As Trees Grow’s subject is a sextet of Umbrian fruit trees, Xenia Pestova Bennett’s performance enhanced by Ed Bennett’s electronics, the resonance and timbre of her Steinway subtly changing across the six movements.

The three-part Ice Creek was commissioned by Pestova Bennett, the piano’s sound combined with Young’s field recordings of an ice-covered waterfall as heard through a set of tuned resonators. The effect is striking, the watery torrents intermittently transformed into rumbling musical notes. Listen through headphones and it’s as if you’re walking outdoors with Young and Bennett, the former’s speech patterns heard through the keyboard. It’s compelling, a potentially gimmicky concept brought to vibrant, colourful life by Pestova Bennett’s zeal. Recommended.

Three Notch’d Road: The Virginia Baroque Ensemble: Shining Shore – Music of Early America (Three Notch’d Road)

Three Notch’d Road: The Virginia Baroque Ensemble: Shining Shore – Music of Early America (Three Notch’d Road)

There’s early and there’s early, the word’s use in this case meaning “unique musical sounds as they would have been heard from the late-17th to the mid-19th centuries.” Shining Shore paints a joyous picture of informal music-making in rural Virginia, the individual items including hymns, popular songs and numbers by Purcell and Handel, some drawn from the contemporary dance music collections compiled by John Walsh and John Playford. Three Notch’d Road suggest that the tunes would have been performed using any instruments to hand, the five members heard on this disc playing, variously, baroque cello, cittern, dulcimer, harp, violin and clarinet, adding vocals when required. The stylistic and emotional range is striking; perky instrumentals like Shaw’s “Jefferson’s March” set against introspective ballads and sacred songs.

Michelle Pincombe and Peter Walker are superb in Jeremiah Ingalls’s “Farewell Hymn”, following it with a light, lilting version of a Philadelphian “Garden Hymn”. The “Dead March” from Handel’s Saul loses little in this arrangement for three players, and a miniature hornpipe by Purcell is exquisitely done, solo violin introducing the group’s other members. An enchanting anthology, very well-recorded. Texts aren’t included, but the vocalists’ diction is so clear that you won’t need them.

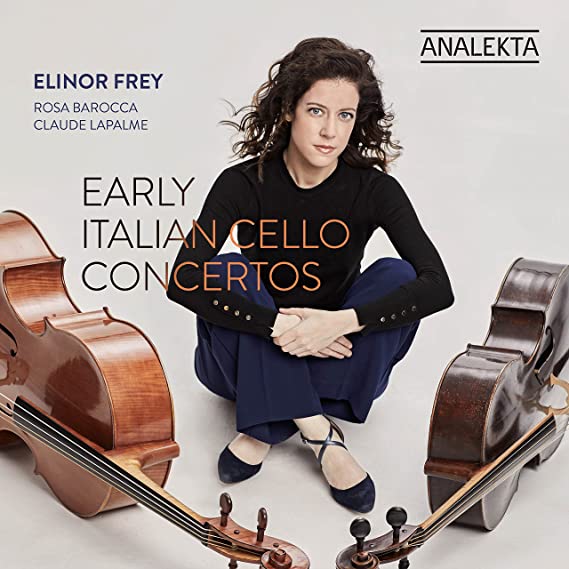

Early Italian Cello Concertos Elinor Frey, Rosa Barocca (Analekta)

Early Italian Cello Concertos Elinor Frey, Rosa Barocca (Analekta)

The cover image tells the story here, and does so rather neatly. These days the cello is an instrument with no doubts about what it is and how it sounds. So what Canadian-American cellist, gambist, and researcher Elinor Frey has done here is really interesting. She has taken us back to the period before 1720, when a “compromise instrument” was emerging from the family of instruments called "violoncello" (literally "small violone"). In other words, the instrument was still in the process of finding out who or what it might be. She plays concertos by Sammartini and Tartini on a smaller four-stringed instrument sometimes referred to as a "tenor cello" or "tenor violin", or, anachronistically as "violoncello piccolo". And because Vandini, the player for whom the Sammartini was writing, played with an underarm bow-grip, so does Frey. She is an elegant, virtuosic and characterful player, and the faster movements are joyous without exception.

I wondered if another player might have more "soul" for the slower movements, but realised that, when I did a direct comparison of the larghetto of the Leo concerto with the recording by Anner Bylsma, it showed how good her judgment is. Frey picks a far more sensible speed here than the Dutchman’s sad plod. And as for the two slow movements by Tartini, Frey takes us somewhere totally different and unexpected. For those who like their false relations to really lurch and scrunch, listen to the last minute of the Tartini A minor Sonata adagio movement, and also the astonishing portamenti in the slow movement of the A major concerto. Frey takes us to a place where baroque music meets steampunk attitude. I loved it. Others might need more cosseting, comforting or sweetness. I doubt if it is possible to remain on the fence. I know it is absolutely appalling form to nitpick reviews that have appeared elsewhere, but I can’t help loving this one: a reviewer describes Rosa Barocca as “a Montreal ensemble of which I was not previously aware”. Hm. Director Claude Lapalme clearly has a French-sounding name, but this rather good baroque band (“newly minted and comprised of musicians from across Canada”, I read) is in fact based some 2200 miles to the west of the shadow of Notre-Dame de Bon Secours... in Calgary, Alberta. Considering this is their debut recording, it bodes very well indeed for them.

Sebastian Scotney

Add comment