theartsdesk in Oxford: Food, Sex and Amis | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Oxford: Food, Sex and Amis

theartsdesk in Oxford: Food, Sex and Amis

Where Shakespeare talks dirty, and very much more

“If I were a woman I would shag as many of you as had pubes and pricks that gave me sexual pleasure…” No less elderly than he is eminent, Professor Stanley Wells – editor of the Oxford Shakespeare and international authority on the Bard – smiles placidly around the room at his blue-rinsed audience. It’s less than 10 minutes into my first event at Oxford’s prestigious literary festival, and decidedly not what I had anticipated.

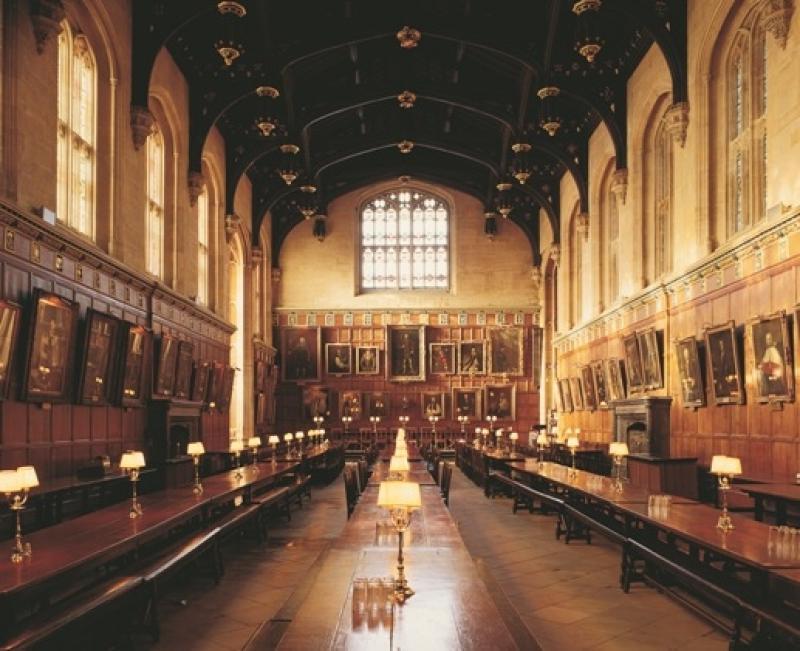

Less frenetic than Edinburgh and more cosmopolitan than Cheltenham, Oxford has a real claim to being England’s finest literary festival (Hay, of course, being just in Wales). It can certainly be described as its most beautiful, calling Christ Church, Corpus Christi and the surrounding Water Meadows home. Fielding the usual line-up of literary figures and public personalities – this year including Martin Amis, Richard Dawkins, Sir Ian Blair, and John le Carré – it is perhaps the city of Oxford itself that is the festival’s greatest selling point. To hear a debate on the Royal Society staged in the Sheldonian Theatre (the work of Royal Society founding member Sir Christopher Wren), or a lecture on Shakespeare’s authorship controversy in Christ Church hall (a venue in which both Elizabeth I and James I are known to have watched plays), adds an experiential element to proceedings that few can match. It was at Christ Church that Lewis Carroll’s Alice famously had her birth (and, more prosaically, where scenes from the Harry Potter films have been shot). Stepping through the college’s magnificent Tom Tower gateway at the start of the annual literary festival is not unlike falling down the fabled rabbit-hole; it’s a bygone world of cloisters and vaulted halls, where Nobel Prize-winning scientists rub shoulders with ex-call-girls, peers with policemen, poets with politicians. A talking caterpillar having a quiet smoke in Peckwater Quad would barely raise a second glance during festival week.

It was at Christ Church that Lewis Carroll’s Alice famously had her birth (and, more prosaically, where scenes from the Harry Potter films have been shot). Stepping through the college’s magnificent Tom Tower gateway at the start of the annual literary festival is not unlike falling down the fabled rabbit-hole; it’s a bygone world of cloisters and vaulted halls, where Nobel Prize-winning scientists rub shoulders with ex-call-girls, peers with policemen, poets with politicians. A talking caterpillar having a quiet smoke in Peckwater Quad would barely raise a second glance during festival week.

You can tell a lot about a year and a nation by the programme of its literary festivals – from the seams and strands of subject-matter that dominate their collective thinking. With more than a thousand events each year, Oxford’s Literary Festival is deliberately diverse, yet in a year whose debates focused on issues of the economy, the security services and police force, not to mention torture, it was curious to see such a discernible emphasis among the book-related events on food, travel, detective fiction, and sex – consolation writ comfortably large in the face of our topical threats and anxieties.  Speaking of sex, it seems only polite to relieve Professor Wells of the role of cheap pornographer. His quotation – a paraphrase, he quickly reassured us, of Rosalind’s epilogue speech from As You Like It, composed by fellow academic Pauline Kiernan – embodies a trend towards such narrowly scatological readings of Shakespeare that Wells himself hopes to challenge in his latest book: Shakespeare, Sex and Love. While acknowledging Shakespeare as the author of “some of the most sexually explicit poems in the English language” (quite a claim at a festival numbering Craig Raine among its guests) and seeking to replace coy editorial notes referring to “bawdy quibbles”, Wells is also keen to contextualise Shakespeare’s use of obscenity and his depictions of sexuality, extracting their nuances. His approach is characteristically humane, balancing a scholarly fascination for details (however gory) with a demeanour as jauntily cheerful as his bright purple jumper. Any octogenarian who can open a lecture with the pronouncement, “I had, of course, a longstanding interest in Shakespeare. I have an even longer-standing interest in sex,” surely deserves respect.

Speaking of sex, it seems only polite to relieve Professor Wells of the role of cheap pornographer. His quotation – a paraphrase, he quickly reassured us, of Rosalind’s epilogue speech from As You Like It, composed by fellow academic Pauline Kiernan – embodies a trend towards such narrowly scatological readings of Shakespeare that Wells himself hopes to challenge in his latest book: Shakespeare, Sex and Love. While acknowledging Shakespeare as the author of “some of the most sexually explicit poems in the English language” (quite a claim at a festival numbering Craig Raine among its guests) and seeking to replace coy editorial notes referring to “bawdy quibbles”, Wells is also keen to contextualise Shakespeare’s use of obscenity and his depictions of sexuality, extracting their nuances. His approach is characteristically humane, balancing a scholarly fascination for details (however gory) with a demeanour as jauntily cheerful as his bright purple jumper. Any octogenarian who can open a lecture with the pronouncement, “I had, of course, a longstanding interest in Shakespeare. I have an even longer-standing interest in sex,” surely deserves respect. Shakespeare was also the subject of Thursday night’s lecture by James Shapiro, author of the bestselling 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. The darkened hall at Christ Church seemed the perfect venue for Shapiro to undertake his engagement with that most shadowy of literary conspiracy theories – the Shakespeare authorship controversy. Shapiro's new book Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? is an attempt to investigate and account for the many claims of Anti-Stratfordians and Oxfordians who would propose alternative candidates for the authorship. Refreshingly reasoned in his approach to this flammable topic, Shapiro explained that the focus of his research was not primarily the question of what people think, but rather why they think it. Keeping this in mind, he proposed a sociological reading of the controversy as a specifically modern – post-1850 – issue. We live, he claimed, in “an autobiographical age”, which in turn shapes our reading practices and priorities. The quest for the true author of Shakespeare’s plays, he seemed to suggest, ultimately reveals far more about us, the readers, than it ever will about the enigmatic man himself.

Shakespeare was also the subject of Thursday night’s lecture by James Shapiro, author of the bestselling 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. The darkened hall at Christ Church seemed the perfect venue for Shapiro to undertake his engagement with that most shadowy of literary conspiracy theories – the Shakespeare authorship controversy. Shapiro's new book Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? is an attempt to investigate and account for the many claims of Anti-Stratfordians and Oxfordians who would propose alternative candidates for the authorship. Refreshingly reasoned in his approach to this flammable topic, Shapiro explained that the focus of his research was not primarily the question of what people think, but rather why they think it. Keeping this in mind, he proposed a sociological reading of the controversy as a specifically modern – post-1850 – issue. We live, he claimed, in “an autobiographical age”, which in turn shapes our reading practices and priorities. The quest for the true author of Shakespeare’s plays, he seemed to suggest, ultimately reveals far more about us, the readers, than it ever will about the enigmatic man himself.

The selection and sheer number of food-themed events (even leaving aside the gin and whisky tasting evenings) was one of the joys of the 2010 festival for those of a gluttonous persuasion. As Rachel Cooke and her panel of food writers discussed so deliciously in Friday’s “Food as Memoir” event, our eating habits and trends are inescapably cultural, records of an individual history or even of a nation or era. Hearing authors such as Anna Del Conte and Josceline Dimbleby discuss this issue in relation to their early memories of food and its formative role in their lives, placed other events such as Tim Hayward and Carolyn Steel’s discussion of London’s changing food scene, or Claudia Roden and Yasmin Alibhai-Brown’s accounts of food from the Diaspora, in context.

An event particularly indicative of our own current times was the “Ministry of Food” lecture by Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall. Tying in with the current Imperial War Museum exhibition, her lively first-hand account of wartime eating practices was liberally sprinkled with hints for contemporary updates and application of wartime principles. While I suspect that few of us will be rushing out to attempt Mock Marzipan or Woolton Pie, the talk’s emphasis on allotments and individual responsibility – along with the stern exhortations of some striking propaganda posters – may well see more of us attempting once again to “Dig for Victory”.  Travel-writing is a reliably popular festival topic in the UK (the wind and rain pummelling the festival marquee for much of the week giving a little clue as to why), and among this year’s many offerings were the delightfully contrasting Anthony Sattin and Jan Morris. Sattin (pictured left) – smoother, if possible, than his name suggests – is a traveller from another era. Deeply tanned in the manner of those 1930s men who could say authoritatively, “When I was in India…,” his floppy-haired English charms have won him quite a following among ladies of a certain age, causing one elderly academic sitting behind me to snort derisively about “groupies”.

Travel-writing is a reliably popular festival topic in the UK (the wind and rain pummelling the festival marquee for much of the week giving a little clue as to why), and among this year’s many offerings were the delightfully contrasting Anthony Sattin and Jan Morris. Sattin (pictured left) – smoother, if possible, than his name suggests – is a traveller from another era. Deeply tanned in the manner of those 1930s men who could say authoritatively, “When I was in India…,” his floppy-haired English charms have won him quite a following among ladies of a certain age, causing one elderly academic sitting behind me to snort derisively about “groupies”.

His latest book A Winter on the Nile takes as its unexpected and fascinating premise a boat trip from Alexandria to Cairo in 1849, on which both Florence Nightingale and Gustave Flaubert – each as yet unknown – were present. The book’s blend of history and travel-writing, and the split-frame focus on its two unacquainted characters, allows it simultaneously to be a travel book, and to interrogate the why of travel itself. With both Nightingale and Flaubert committed diarists and scribblers, the book’s real joy is its extraordinary source-material, especially when parallel accounts are placed alongside each other. Sattin drew our attention to the day on which the pyramids were first sighted. While his poet companion Du Camp delivers predictably purple prose, Flaubert’s own diary records blandly, "Pyramids. Three", while Nightingale omits any mention at all.  Also peddling her latest book, Contact! A Book of Glimpses, was Jan Morris. Blowsily eccentric, her undeniable charisma could not be more different to that of the polished Mr Sattin, and one suspects that their travelling styles are equally distinct. In a departure from previous works, Contact! is as much a tale of people as places. Moving from Australia to Dublin, Gibraltar to Texas, Morris’s glimpses are witty and warmly honest – except where aesthetic elegance demands that imagination play a part – and if they occasionally teeter on the brink of sentimentality, they always manage to right themselves with a throaty cackle of self-mockery.

Also peddling her latest book, Contact! A Book of Glimpses, was Jan Morris. Blowsily eccentric, her undeniable charisma could not be more different to that of the polished Mr Sattin, and one suspects that their travelling styles are equally distinct. In a departure from previous works, Contact! is as much a tale of people as places. Moving from Australia to Dublin, Gibraltar to Texas, Morris’s glimpses are witty and warmly honest – except where aesthetic elegance demands that imagination play a part – and if they occasionally teeter on the brink of sentimentality, they always manage to right themselves with a throaty cackle of self-mockery.

There was a tremendous variety of tone among the festival’s individual author events. Among the more relaxed and conversational was Dave Eggers on his new book Zeitoun. Characteristically open and terrifyingly fluent, he spoke of Katrina and of American national security with a wry humour that at no point belittled the seriousness of his subject-matter. In a week where discussions on biography and memoir were prevalent, Eggers was almost alone in his affiliation to absolute truth, stressing the seriousness of the act of bearing witness. I doubt anyone left the room without a renewed admiration for Eggers and the liberal humanist remit of his publishing company McSweeney’s.  At the other end of the spectrum was this year’s English-Speaking Union lecture delivered by Ben Okri (pictured left). Delicately inscrutable as a cat, fastidiously padding his way around difficult questions or simply staring down the innocent questioner, it was one of the more deeply uncomfortable experiences of the week. Eschewing a conventional speech in place of a cryptic “medley with a central structure”, the significance was somewhat elusive, especially as Okri refused to reveal his theme beforehand. Discussing (broadly) issues of European myth-making and the weight of tradition, Okri’s oblique and aggressive meditation did little to advance the sense of trans-national intellectual fellowship that the ESU is surely designed to promote.

At the other end of the spectrum was this year’s English-Speaking Union lecture delivered by Ben Okri (pictured left). Delicately inscrutable as a cat, fastidiously padding his way around difficult questions or simply staring down the innocent questioner, it was one of the more deeply uncomfortable experiences of the week. Eschewing a conventional speech in place of a cryptic “medley with a central structure”, the significance was somewhat elusive, especially as Okri refused to reveal his theme beforehand. Discussing (broadly) issues of European myth-making and the weight of tradition, Okri’s oblique and aggressive meditation did little to advance the sense of trans-national intellectual fellowship that the ESU is surely designed to promote.

As with their pop music cousins, literary festivals also have their headline acts. I was amused to note that Martin Amis – one of this year’s star performers – drew a respectable, but far smaller crowd than had filled the Sheldonian for JM Coetzee’s visit recently; following Amis’ rather petulant attack on Coetzee in Prospect magazine, it seemed that the Oxford audience were voting with their feet in this particular battle. The event itself – readings from The Pregnant Widow and Amis in conversation with long-time crony Craig Raine – was rather erratic, with Raine cheerfully announcing at the outset, “We’ve rehearsed this very little – if at all.” The result was rather like sitting in the ladies’ lounge of a private gentleman’s club – privy to, but never fully invited into the intellectual cabal. That The Pregnant Widow is both funny and sharply drawn I would not wish to deny, but Amis does himself few favours in his battle against the “misogynist” label that dogs him by pronouncing so grandly and confidently upon women. Laughter was had in plenty, but this was perhaps greater testimony to the tolerant generosity of the audience rather than that of the speaker.

One particularly fascinating strand at this year’s festival was the series of panel debates, many running in conjunction with the annual Orwell Prize for political writing. Dividing their attention between matters national and international, together they formed an image of a nation – and a world – in a state of acute anxiety, with even fundamentals like free speech finding themselves back on the table for discussion. A debate on "The Future of Policing" proved surprisingly heartening, however. Described by Sir Ian Blair as a “touchstone political issue”, it certainly drew an impassioned series of questions from the floor. Tackling issues of accountability and affordability from practical and academic standpoints, Blair – together with Roger Graef and Robert Reiner – gave both reasoned and reasonable responses, drawing on everything from Max Weber and John Stuart Mill to Raymond Chandler in the process.

The Oxford Literary Festival is an event of contradictions; set between the civilised splendour of the dreaming spires and the muddy Meadows with their herd of Longhorn cattle, it combines authentic high-thinking with a pleasingly English lack of pomp. If you can get past the slightly soggy middle-Englishness of the central marquee, with its hand-whittled sponge cakes and home-grown ceramics, there’s some big and generous thinking going on. And if, like Prufrock, few of us have the strength to push questions to their absolute crisis-point in such a setting, then so much the better. Cake and civilised conversation: could there be a better symbol of all that is good about Oxford?

- The Sunday Times Oxford Literary Festival ends today.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Gibby Haynes, O2 Academy 2, Birmingham review - ex-Butthole Surfer goes School of Rock

Butthole Surfers’ frontman is still flying his freak flag but in a slightly more restrained manner

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Cat Cohen / Lachlan Werner / KC Shornima

Defying a health scare; a surreal invention & a distinctive new voice

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Cat Cohen / Lachlan Werner / KC Shornima

Defying a health scare; a surreal invention & a distinctive new voice

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Album: Adrian Sherwood - The Collapse of Everything

The dub maestro stretches out and chills

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Music Reissues Weekly: The Residents - American Composer's Series

James Brown, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Hank Williams as seen through an eyeball-headed lens

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Album: Dinosaur Pile-Up - I've Felt Better

Heavy rock power pop trio return after an unwanted lengthy break

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Emmanuel Sonubi / Joz Norris

A second chance at life & a fantastical tale about artistic endeavour

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Emmanuel Sonubi / Joz Norris

A second chance at life & a fantastical tale about artistic endeavour

Comments

...

...

...