In this best-selling Korean novella, recently translated into English by Jamie Chang, Kim Hye-jin offers us the perspective of a Korean mother. It’s narrated entirely from the perspective of a woman of around 60 who has a daughter in her thirties and focuses on her inability to understand what her daughter, Green, wants from life and why she’s decided to live openly as a lesbian with her partner Lane:

“Gay? The word rushes into my head and shoots through without permission. Words come to me so violently, without warning, before Lane can say another word, I quickly manage to correct her. My daughter is not that kind of person.”

Although the novel has the potential to lean into clichés, the viewpoint makes room for complication. Hye-jin’s close first-person narration mines the empathy of the mother’s position: her troubled state, her inner conflict, her traditional views that do not fit within the changing world around her. The widowed mother is terrified by what she witnesses in her job as a carer for the elderly. She fears that without a traditional life – a husband and children – her beloved daughter will not only end up alone, but unhappy and penniless. This complicates Hye-jin’s portrait of a deeply homophobic mother, whose opinions are shaped by a distorted kind of love and far-reaching fear: “It breaks my heart. Why won’t she try to live a normal life?”

Hye-jin explores the precarious and conflicted reality of a low-paid worker in Korea, who continues to cling to a system that has not only failed to support her, but continually exploited her, too. This exploitation has manifested itself in a psychological sense: the narrator lives in a constant state of fear, so much so that it often borders on terror. Throughout her life, she has done everything that tradition required of her. She married respectably, had a child, and worked tirelessly for the capitalist system. All that remains, however, is a dead husband and a low-paid job. Hye-jin lets the reader in on a world where even those who follow the rigid rules of a conservative social system and police their own family members are still not able to reap the benefits of this narrow existence. Through the narrator's inability to unlatch from her hardened beliefs in the supremacy of the heterosexual nuclear family, Hye-jin lets us into a society that is falling apart at the seams.

Hye-jin builds narrative tension by juxtaposing the narrator’s daughter, Green, with the narrator’s primary patient, Jen, drawing multiple parallels between them. Jen took an unconventional path in life as a highly successful yet single woman, yet her health is now rapidly declining at the hands of the underfunded care home where the narrator works. Filled with compassion for Jen, the narrator passionately advocates for her rights to better healthcare and for her to be given the chance to make decisions autonomously. There is a clear contrast with the narrator’s attitude to Green: she cannot comprehend her daughter’s fight for LGBTQ rights after her university colleagues are fired for discussing sexuality in their lectures. This juxtaposition is critical in illustrating the mother’s capacity for compassion: “Who in society is deserving of our compassion and empathy?”. The self-questioning nature of Hye-jin’s narrator allows her to explore the tensions between mother and daughter with great deftness. The mother’s socially conservative values clash against her unwavering love for her daughter: how best to protect Green in a dangerous, changing world?

Hye-jin builds narrative tension by juxtaposing the narrator’s daughter, Green, with the narrator’s primary patient, Jen, drawing multiple parallels between them. Jen took an unconventional path in life as a highly successful yet single woman, yet her health is now rapidly declining at the hands of the underfunded care home where the narrator works. Filled with compassion for Jen, the narrator passionately advocates for her rights to better healthcare and for her to be given the chance to make decisions autonomously. There is a clear contrast with the narrator’s attitude to Green: she cannot comprehend her daughter’s fight for LGBTQ rights after her university colleagues are fired for discussing sexuality in their lectures. This juxtaposition is critical in illustrating the mother’s capacity for compassion: “Who in society is deserving of our compassion and empathy?”. The self-questioning nature of Hye-jin’s narrator allows her to explore the tensions between mother and daughter with great deftness. The mother’s socially conservative values clash against her unwavering love for her daughter: how best to protect Green in a dangerous, changing world?

Kim Hye-jin’s writing style, precisely translated by Chang, can be demanding: the narrative doesn’t follow a set chronology; instead, it shifts according to the logic of the narrator’s thoughts and feelings, leading to abrupt changes in time and setting. These sudden switches seem to mirror the difficulty the narrator has in adapting to the changing world around her: she is uncomfortable, out of sync. Such shifts enable the reader to experience a similar discomfort, creating empathy for the narrator, while also putting her reliability in question – a reminder that we shouldn’t get too close.

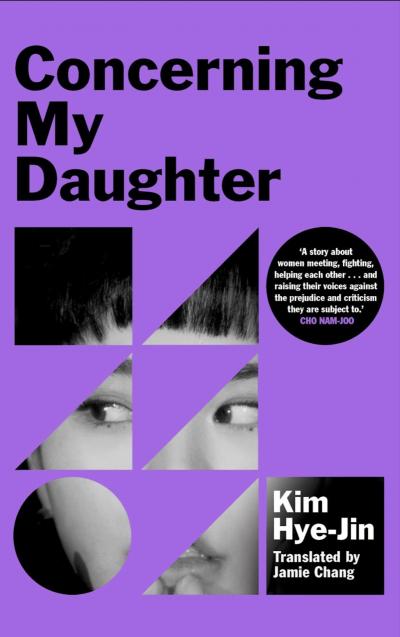

- Concerning my Daughter by Kim Hye-jin, translated by Jamie Chang (Picador, £14.99)

- More book reviews and features on theartsdesk

Add comment