The Elixir of Love, English National Opera | reviews, news & interviews

The Elixir of Love, English National Opera

The Elixir of Love, English National Opera

Triumphant return for Jonathan Miller

It takes roughly, ooh, about five minutes for Jonathan Miller's new production of Donizetti's The Elixir of Love (whose 1950s set had the audience gawping smilingly within seconds) to start electrifying the nerve-endings into orgasmic spasm.

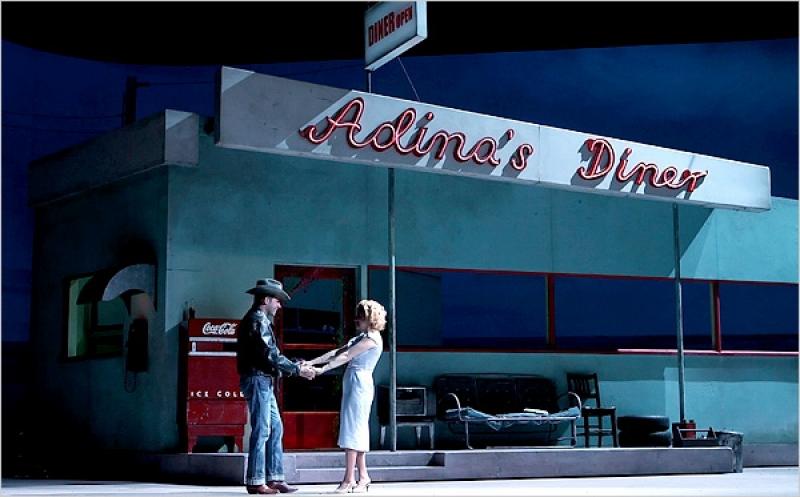

It takes roughly, ooh, about five minutes for Jonathan Miller's new production of Donizetti's The Elixir of Love (whose 1950s set had the audience gawping smilingly within seconds) to start electrifying the nerve-endings into orgasmic spasm. With one sexy shake of her hips, Sarah Tynan's immeasurably winning blonde-bobbed Adina, a Marilyn Monroe-like tease, the till-girl and owner of a Midwest diner and filling station, which rotates - almost as stunningly as Tynan - amid the nothingness of desert and sky, clutches a mop and swings this music and its troop of jiving dotted quavers into a boppy, rock 'n' rolling, Little Richard heaven. It was just a small hint of the joys to come.

Dr Miller has become a sort of court physician to the operatic art form. He will visit an ailing operatic patient, a doddery old staple classic, an Alzheimer's-riddled bit of bel canto. He'll check its pulse, inspect its ears, scan its flab and dive it into emergency operation: sometimes just intense psychological therapy, sometimes a full surgeon's op. The resulting transformations are as successful as the Hollywood snip, buying these former operatic glamour-pusses at least four more decades of public mileage.

Well, he's done it again. Another successful hospitalisation delivered. Donizetti's L'Elisir d'Amore becomes The Elixr (the swallowed 'i' indicating, yes - traditionalists, fetch your smelling salts - full American accents among the cast) of Love and sometimes Lurve. The pastoralism of librettist Felice Romani's Italian setting has been replaced by the capitalism of 1950s America.

Within minutes of Adina's teasing jive in front of the love-struck Nemorino, a Cadillac Convertible rolls into town and with it the sweet talk of the American travelling salesman, Andrew Shore's beige-suited and fraudster-footed Dr Dulcamara, clutching a box of wonder cures. Dulcamara's hoary old comic aria as he addresses the community is transformed into the stuff of MGM musical gold: a string of magnetically performed one-liners about the elixir's medicinal and non-medicinal claims (for "oversized posteriors" and "gas from your interiors") for which Shore and librettist Kelley Rourke deserve huge credit.

With one swig of the elixir Nemorino slowly feels himself becoming increasingly irresistible. In fact the 40 per cent alcohol that makes up the potion is doing that, loosening him up and transforming his lady-gathering fortunes. Few operas have such a instructive little moral in it like this. A moral that we could all learn from and live by. The essence of this one: chill out and you'll get the lady. Miller delights in Nemorino's flowering. From a solipsistic weediness, Nemorino fixed to the corner of the diner, his knees locked in a knackety embrace for his opening aria, "She will never notice me" - with Adina looking straight on of course - emerges a moody James Dean-like leather-clad cowboy in the second act.

Miller also delights in manipulating Tynan's exquisitely lithe and malleable form. I have never seen an opera singer do so much with so little. Her slip of a body was an endlessly expressive canvas: now twisting into a rage, her arms parked jaggedly on her hips as Nemorino appears to ignore her, now shrugging her little shoulders winningly for her gum-chewing army hunk, Sarge Belcore (David Kempster).

That Tynan could make so much of all these little twists and turns in personality and mood while maintaining the most natural, the most believably effortless and sexy exterior I have ever seen in an operatic actress is astonishing. Her singing was no less awesome. She dispatched all the coloratura high climbing without a second thought. And yet it was often the beauty of her descents - whose equally challenging difficulties (though coming after the money-shots) should never be overlooked or underestimated - the beauty of the finishing, that really showed off the extent of Tynan's talents. Truly, here, a star was born.

And as always with Miller's productions, the harder you looked the more delights were to be found. In Miller many of the really spine-tingling moments come in the tiny departures from operatic convention, in what the singers decide not to do, as much as what they do do. What a delight to see Tynan controlling her arms, keeping them by her side, or allowing them to fiddle with her hair, so that maximum meaning could be wrought from them when necessary. And what a joy to see the chorus not act as an undifferentiated mass of theatrical wannabes (as often happens in, ahem, the other place) but as individuals in a reality we recognise.

Then there are all the exquisitely realised details Miller does provide: the mimicry of Elvis from Andrew Shore's Doctor, and Betty Boop from Tynan during the wedding celebrations, the gossip and walking on hot coals in the queue for the ladies lavs where a Rizzo-like Giannetta, the superb Julia Sporsen, divulges Nemorino's new-found wealth, the dusty, rusty corners of the Hopper set designed by the brilliant Isabella Bywater. Oh, the Hopper set. I could wax lyrical about that Hopper-inspired set for a good few more hundred words. But I won't. Suffice to say, it's a perfect little green and red revolving box.

So was there anything at all that creaked? Possibly, yes. John Tessier's voice didn't flower as much as his character, remaining strained and unaffecting, particularly in "Una furtiva lagrima". And the orchestra was noticeably ragged, the result I suspect of treating the music - actually hugely challenging in terms of phrasing and texture - with less respect than it deserves. I don't think Spanish conductor Pablo Heras-Casdo was entirely to blame for this. He was obviously concentrated on providing an orchestral mirror to the 1950s feel of the production, buzz-cutting dotted rhythms and jazzing up chromatic lines, all of which suits the light-footed musical ways of bel canto to a T.

The one real oddity was the gulf between the brilliance of the ensemble acting between the lead five players, particularly the reactive fire from Andrew Shore, still the finest operatic comic singer on stage today, and the lack of balance in the ensemble singing of duets, trios and quartets. Something to work on, there. Overall, however, like his Mikado, Rigoletto, The Barber of Seville or Cosi, Miller has hit the jackpot with The Elixir. The ENO has another classic on its hands. And you won't see it surpassed I'd say for at least, ooh, the next 30 years.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Comments

...