First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

In September 2022 I had an email from my American friend Richard Nelson: "Would you like me to write you a play?" Such an offer probably comes the way of very few actors and I was bowled over by it. My astonished and grateful response was tempered with a little uncertainty.

I didn't want it to be too much about my illness, and Richard assured me it would also be about many other things. He said, "I'll send you something." Two days later an attachment arrived which I thought would be a couple of pages of ideas or an outline. It was a 42-page script.

Richard and I first met in 1990 at the RSC in Stratford when the late Roger Michell cast me in Richard's play Two Shakespearean Actors. Roger's assistant director on the production was one Clarissa Brown. It was a season of enduring friendships, actually quite rare in the theatre, and in subsequent years Richard and I stayed in touch.

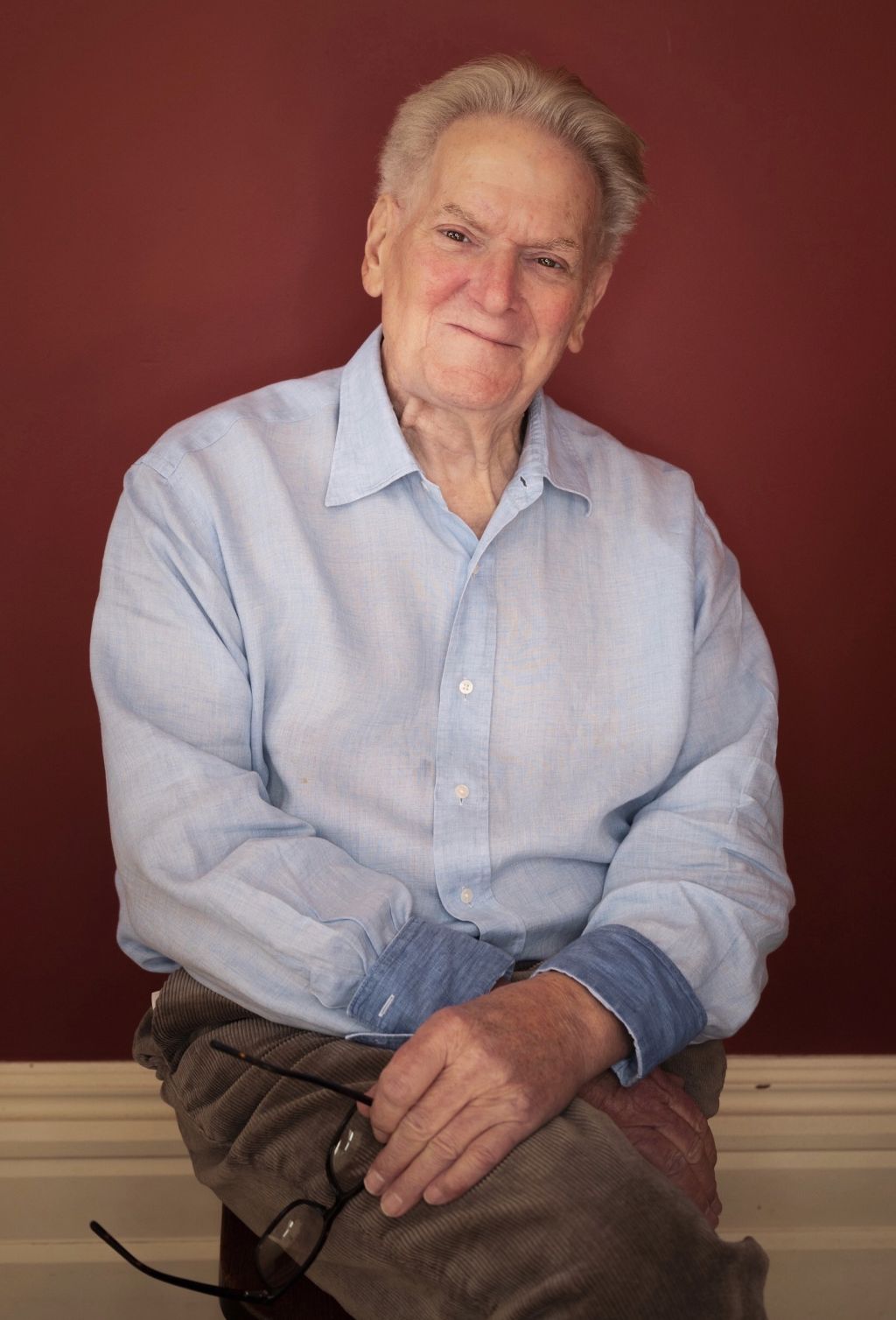

In February 2021, during the second Covid lockdown, I was diagnosed with oral cancer and had surgery at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital for the removal of my upper-right jaw and part of my palate: pretty devastating for anyone, let alone an actor, but the prognosis was good. (pictured below, Paul Jesson, photo c. Lise Leino)

I did, however, undergo six weeks of radiotherapy and this, while hopefully ensuring no recurrence of the disease, did damage my tongue, making speech and eating (rather important to me) even trickier than it might otherwise have been. Words like "grief" and "grave" were especially difficult. Although my home is in London, I was at the time living in Devon. In 2017 Clarissa Brown and I re-met and, much water having flowed under the bridge, we began a relationship that resulted in our happily spending lockdown together at her home on the river Exe. During that time Richard and I emailed only occasionally – there didn't seem much to report – but I eventually told him about the surgery and later the three of us met on Zoom. He says it was seeing my altered appearance and hearing my altered voice that made him think of offering to write me a play. He also wanted to write it with Clarissa in mind as its director.

I did, however, undergo six weeks of radiotherapy and this, while hopefully ensuring no recurrence of the disease, did damage my tongue, making speech and eating (rather important to me) even trickier than it might otherwise have been. Words like "grief" and "grave" were especially difficult. Although my home is in London, I was at the time living in Devon. In 2017 Clarissa Brown and I re-met and, much water having flowed under the bridge, we began a relationship that resulted in our happily spending lockdown together at her home on the river Exe. During that time Richard and I emailed only occasionally – there didn't seem much to report – but I eventually told him about the surgery and later the three of us met on Zoom. He says it was seeing my altered appearance and hearing my altered voice that made him think of offering to write me a play. He also wanted to write it with Clarissa in mind as its director.

The script was a tapestry of stories and quotations – some funny, some bizarre – as well as incidents recalled, people remembered. Across seven scenes, it encompassed loss, friendship, poetry, questioning – a conversation on a journey. Richard had mined his notebooks of many years and the elements of an abandoned play. At first it seemed an elusive farrago of disparate themes, some of them very moving, all with the oblique, unresolved quality typical of Richard's writing. Little in this first draft related to me other than the fact that the sole character is an actor who had been under the surgeon's knife for oral cancer. He calls himself a Shakespearean actor.

I've been in about 30 productions of Shakespeare plays but have never thought of myself in that way. If asked for a label other than "jobbing", I might say I'm a Royal Court or Joint Stock actor, one who relishes being in a company working on new plays and being part of a creative collaboration. [Jesson won a 1987 Olivier Award for the Royal Court premiere of The Normal Heart.] That is exactly what An Actor Convalescing in Devon was about to become.

Two months after the first draft arrived, Richard was in Paris working with Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky on translations of Russian plays. Clarissa and I went to meet him there. He wanted to know our response to his play and whether it brought to mind any stories and experiences of ours. He is kind enough to say he stole them, but they were, of course, freely and gladly offered. Some of mine were autobiographical, some were memories of friends and others were theatrical anecdotes. Clarissa, a Devonian born and bred, had thoughts about her home county but also of Sicily and, crucially, about my post-operative state, details of which I'd either forgotten or was never aware of. Wherever he thought them appropriate, Richard wove our offerings into the fabric of the play.

In June last year Richard was again in Paris and there was an opportunity to read the play for him and a small audience at Ariane Mnouchkine's Théâtre du Soleil where he was directing his play Notre Vie dans l'Art. The reading proved more successful than we could have hoped. The farrago had revealed itself to be a beautiful, subtle testament to survival and the healing power of art. It was clearly ready for the stage.

There were two main obstacles: finding a theatre and my having to learn it. We sent the script to several producers but received little encouragement other than being told how much they loved Richard's work. Out of the blue in early November Richard forwarded an email from Greg Ripley-Duggan. He'd been enchanted by the play and was offering us a production at Hampstead Downstairs. We were over the moon. Hampstead had always been my theatre of choice. It was to be a companion piece to April De Angelis' The Divine Mrs S in the main house, two plays about actors, and Clarissa, continuing the collaboration, has brought together a dream design team of Rob Howell (set), Rick Fisher (lighting) and Mike Walker (sound).

Now all I have to do is learn it.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Add comment