Derek Owusu: Losing the Plot review - the finest perfume | reviews, news & interviews

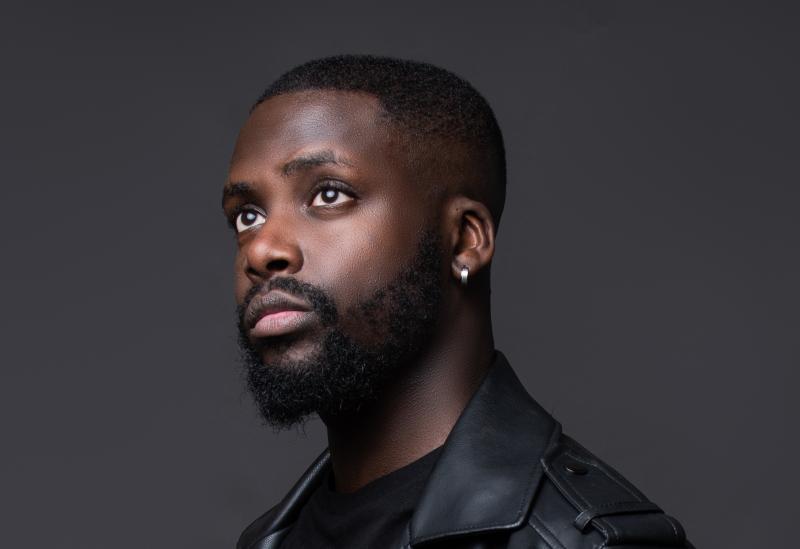

Derek Owusu: Losing the Plot review - the finest perfume

Derek Owusu: Losing the Plot review - the finest perfume

Smells and scent bind this poetic study of identity and diaspora

Derek Owusu’s debut That Reminds Me won the Desmond Elliot Prize in 2020. When asked what it was that she loved most about Owusu’s semi-autobiographical 117-page book, Preti Taneja, chair of the judges (and winner of the prize herself in 2018) answered, without hesitation, “the form” and Owusu’s “compression of poetic language”.

That Reminds Me was described as a novel despite its fragmented structure and its prose slip-sliding into poetry. Losing the Plot is similarly slender and hybrid in form. It is divided into three parts: Landing, Disembarking, Customs and Immigration. The book’s presentation, with its narrow margins of text – which give space to each memory (varying from just a few lines to a couple of pages in length) – and its language (which often begs to be read aloud), suggest that it might reside on poetry shelves. Yet it will confound those wishing to attach a definitive genre. The text is annotated with sidenotes, as if the narrator is leaving WhatsApp voice notes for the reader, and his tone is personal: fam. These interjections are poignant and not without humour. They breathe directness on the steamed-up windows of poetry, sometimes with understatement: “Being an immigrant is stress”.

The contrast in tone between the poetry and the colloquial sidenotes demonstrates Owusu’s complex exploration of linguistic identity. In many respects, Losing the Plot is the child of his essay “Mother tongue: the lost inheritance of diaspora”, published in 2017, in which he echoes James Baldwin’s words that “Language is the most vivid and crucial key to identity”, mourning his mother’s decision not to teach him Twi, her first language (and the spoken language of around 8 million people in Ghana). He believes she “probably perceived” that he was without identity as a newborn and must not recognise himself as Ghanaian; emphasising this in Losing the Plot, Owusu includes a telling sidenote: the narrator’s mother “has no problem telling me I’m not Ghanaian. She became a citizen before I was even born”.

The contrast in tone between the poetry and the colloquial sidenotes demonstrates Owusu’s complex exploration of linguistic identity. In many respects, Losing the Plot is the child of his essay “Mother tongue: the lost inheritance of diaspora”, published in 2017, in which he echoes James Baldwin’s words that “Language is the most vivid and crucial key to identity”, mourning his mother’s decision not to teach him Twi, her first language (and the spoken language of around 8 million people in Ghana). He believes she “probably perceived” that he was without identity as a newborn and must not recognise himself as Ghanaian; emphasising this in Losing the Plot, Owusu includes a telling sidenote: the narrator’s mother “has no problem telling me I’m not Ghanaian. She became a citizen before I was even born”.

The text is scattered with Twi and references to his narrator yearning to speak the language, and his mother’s frustration at this. In juxtaposition, he imagines her learning English right from her arrival in the UK with obronis (foreigners) “twisting and polishing her tongue”; how “her beat-up words will have to do”; and how:

She tries to translate idioms and sayings

– words placed by how they’re spoken as

Opposed to their expression

This theme of Mother Tongue is silhouetted in a vignette of attachment when the mother is out with her daughter:

She stops the buggy and faces her baby,

pushing out her tongue

playfully, acting, hoping, clicking,

She struggles to cross her eyes,

but hears a forgiving giggle as the reply.

The narrator responds with corresponding forgiveness (at not being taught Twi) to the cadence of his mother’s English:

He prefers son to any other calling, loves

the drop of tone through those three letters

sounding stretched but comfortable in their

balance, a name he’s proud of …

For those of us fortunate to be secure in our home, Owusu leaves us in no doubt of the 24/7 harsh reality of stress endured by immigrant communities. The mother is continually playing catch-up with her new identity. In one of the most moving images, she’s pictured in the bathroom after a shower, her head wrapped in a “towel for tresses”, watching the condensation on the mirror, the drops likened to her tears as:

She brushes her teeth out of time with

her reflection (…)

She lives in a perpetual struggle to pay the rent, as well as to find somewhere permanent she can call home, “constantly handing over key being the motive of her life”. Yet: “My mum’s never really complained … Always going somewhere, holding herself back… This woman would never rest”. She works endless shifts as a cleaner:

Her bleached palm circles clockwise, swift,

trying to wipe clean who or what came

before …

It’s impossible not to draw inference from her bleached hands, an image repeated several times throughout the text. Or from a similar emphasis on the word “stretch” (“she’s thin from stretching herself”; “she looks up into a bulb that slowly bloats / the eye so that skin can stretch”; “she holds and stretches her skin”) and other repetitions (of “settle”; “survey”; “impression”; “scalding” and “scour”) that suggest the relentlessness of fitting in in an often racist society. She is unable to live freely: Owusu frames her in a “tall enclosed building” and “compressed” in a lift. She develops a fear of looking up, for “unbearable is the weight of the sky". The all-consuming pressure of just being has become “unbearable”.

The toll on her mental health is vividly depicted. She has become “the prey of the world waiting to be taken”; her “smiling cheeks” round as “cherries” are replaced by a “fading body” and “frail identity”. As a teenager, the narrator learnt to recognise the signs of his mother’s depression :

He saw it all, could tell she failed to feel

from months before, no shock, no reaction

as he watched plantain oil pop onto her

skin (…)

Devotees of the psychologist Jean Piaget would no doubt fall upon the narrator’s hyper vigilance as an example of “assimilation”: witnessing his mother’s behaviours from infancy will foreshadow his beliefs and perceptions as an adult. And as an adult, after a night out of heavy drinking, he falls flat onto the street and “pushes himself to his feet … and questions the distance between here / and home. Whose home?”

The narrator’s mother may not have kept Ghanian culture alive with Twi but the Broadwater Farm’s Ghana radio station plays often in the background. She cooks her children Ghanaian dishes and her cooking permeates the text as it clings to their walls; you want to scratch the text to smell her pepper soup, Fufu and ties. Owusu puts olfactory imagery to powerful use. Less appetising is the stench of bigotry. When the narrator is a child, he’s invited to a party. They arrive at the birthday boy’s flat and knock at the door. Someone checks who it is, and when his mother replies the voices behind the door are “shushed, giggles suppressed”. Undaunted, our narrator peers through the letter box and calls his friend. His gaze is met by a woman’s, who “figures her lips” and spits at him. He wipes his face, “still able to smell the odour / around his nose as it continued to fall to his / lips”. That the boy smells the woman’s glob of saliva intensifies the vileness of the image.

We are told that his mother’s fingers smell of “stewed bleach” before we learn that her hands have been bleached from cleaning. And the reader is brought to the mother’s bedside with the scent of “Plum, peach and orange blossom” in the air while she:

lies in bed unable to move anything but

her hanging wrist, fragrant and exposed,

though moments ago she rose ready for

work, shimmying through the Red Door

Owusu enables us to feel her depression more acutely by allowing us to smell her perfume, Elizabeth Arden’s Red Door (and note his pun on its middle note: “rose”). The Arden blurb promises that their “signature scent will unlock your world … instantly get you noticed …create an impression of style”: perfect, you would imagine for someone creating their new identity.

In the epilogue, the narrator is replaced by Owusu as he interviews his mother in the spring of 2019 “to ask a few questions about life” when she arrived in the UK. She is hilariously unforthcoming, and it proves a “fact-less” interview, punctuated by much laughter (and gentle frustration on Owusu’s part). The only tangible fact to be gleaned is their evident love for one another. Meanwhile, in later life, and in a cruel twist of irony, the narrator’s mother is left atrophied with just a “few drops” of memory while “a Union Jack / sways outside the home she’ll die in”. During one visit, he gives her a bottle of Red Door, presumably in the hope of unlocking a trove of memories:

She lifts the top and sprays, both move

their heads around the room to catch the

unravelling aroma.

Never has Elizabeth Arden received such sublime product placement: they owe Owusu a fortune.

Owusu’s intricate layering of form and language (in all its meanings), and the blur of the author and his mother’s life with that of their fictional counterparts, reflects the complexity of identity and memory in the most unique of ways. He cuts exquisite shape from the most harrowing of fabrics: diaspora, history and self are stitched seamlessly yet worn so lightly. Losing the Plot will forever linger in your mind for Owusu is also the finest perfumer. Remember: “Man can’t be arrogant and self-aware at the same time; feel sorry for people like that.”

- Losing the Plot by Derek Owusu (Canongate, £12.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment