Nightclubbing: The Birth of Punk Rock in NYC review - cheap thrills | reviews, news & interviews

Nightclubbing: The Birth of Punk Rock in NYC review - cheap thrills

Nightclubbing: The Birth of Punk Rock in NYC review - cheap thrills

Chasteningly mundane history of punk venue Max's, plus Sid Vicious' last stand

Bankruptcy, rubble, rape and murder: Manhattan in the Seventies could be grim, as multiple New York punk memoirs make clear. The trade-off was the art, steaming and burning in the stinking, crucially cheap degradation. Punk was just one symptomatic part of a crumbling Lower East Side where old Beats, folkies, jazzers, poets, theatre, film and visual artists also lived.

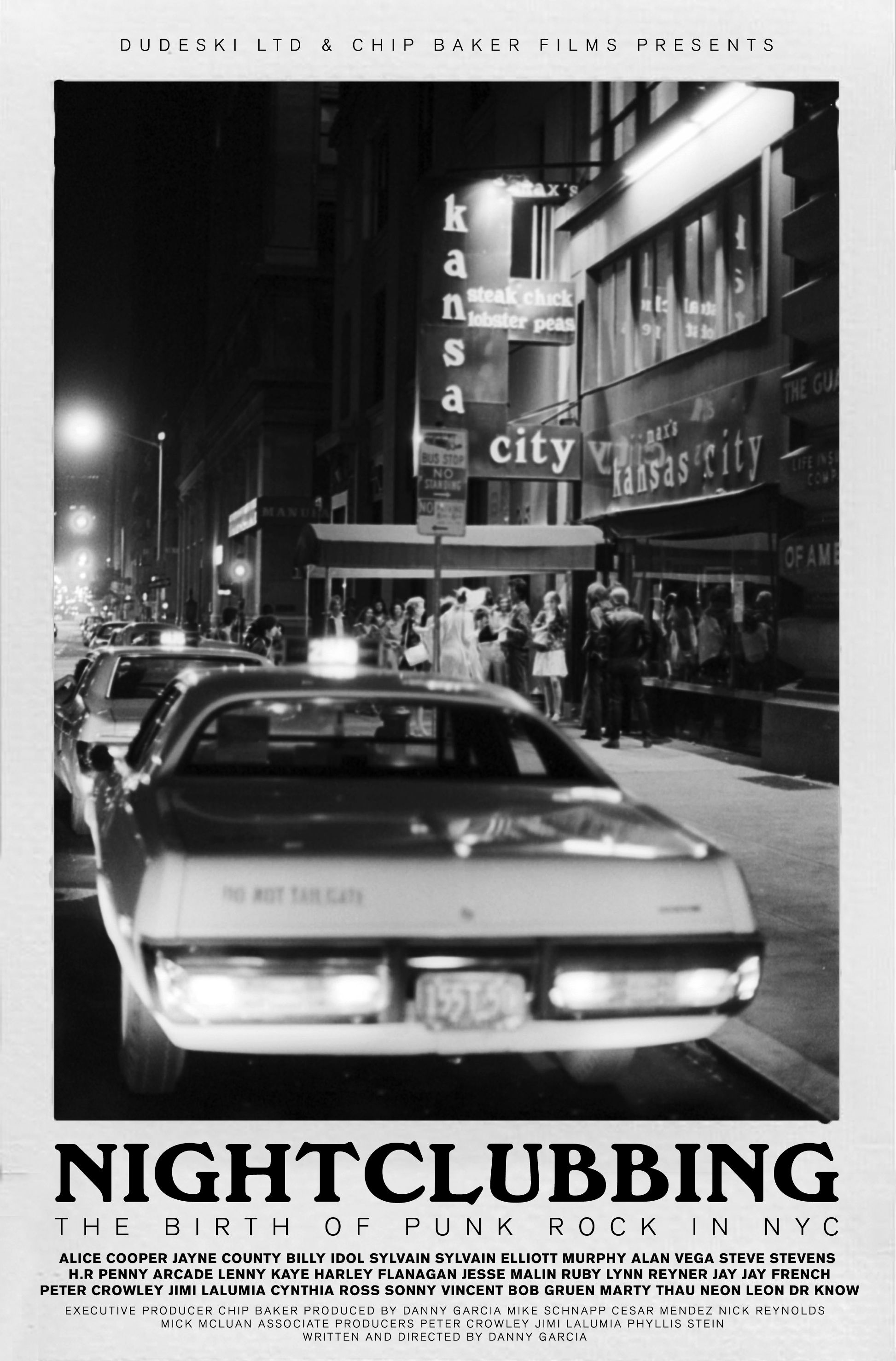

The point of Danny Garcia’s Nightclubbing doc is to stake Max’s, Kansas City’s claim as a punk epicentre, and challenge CBGB’s fabled status. Despite a few key interviewees, his low-budget, artless film does no one any favours.

Max’s was always part of New York punk’s foundation myth, the place where the New York Dolls played and pre-stardom Bowie and post-Velvets Lou Reed met. But its greatest notoriety was pre-punk, when Warhol personally held court in its back room, whose psychic temperature is caught in Mary Woronov’s Swimming Underground: My Years in the Warhol Factory. The sometime Factory and Chelsea girl recalls her first visit, “stuck in the doorway where all the nobodies hesitated”. “When I finally left Max’s,” she writes of a later occasion, when Andrea Whips typically danced on a table and startlingly inserted a champagne bottle, “it was four in the morning and there was no lower level to sink to.”

Max’s was always part of New York punk’s foundation myth, the place where the New York Dolls played and pre-stardom Bowie and post-Velvets Lou Reed met. But its greatest notoriety was pre-punk, when Warhol personally held court in its back room, whose psychic temperature is caught in Mary Woronov’s Swimming Underground: My Years in the Warhol Factory. The sometime Factory and Chelsea girl recalls her first visit, “stuck in the doorway where all the nobodies hesitated”. “When I finally left Max’s,” she writes of a later occasion, when Andrea Whips typically danced on a table and startlingly inserted a champagne bottle, “it was four in the morning and there was no lower level to sink to.”

Patti Smith first dared the back room in 1969, after the Warhol heyday, when the now “absent silver king” had made it “the social hub of the subterranean universe”. Smith’s Just Kids further records going upstairs later that year and being among the few dancers when the Velvet Underground played Max’s to perhaps 100 people, and began its rock’n’roll transition. Both writers make you miss having the chance, talent or toughness to experience a place they steep in poignantly recalled experience.

Garcia calls plainer witnesses, who give a messier, perhaps more realistic picture. Generic rock mostly soundtracks a movie which clearly lacks the cash for much apposite music or, apparently, chronologically relevant stills of chameleon artists such as Bowie. Nightclubbing does have footage of the likes of Ruby & The Rednecks, the Testors and Sid Vicious at Max’s. If you were hankering to time-travel back to those golden punk nights, this gives a good idea of how ordinary, even plain awful, they could be. There’s something dispiriting, and chastening, about a film too cheap to feed our fantasies.

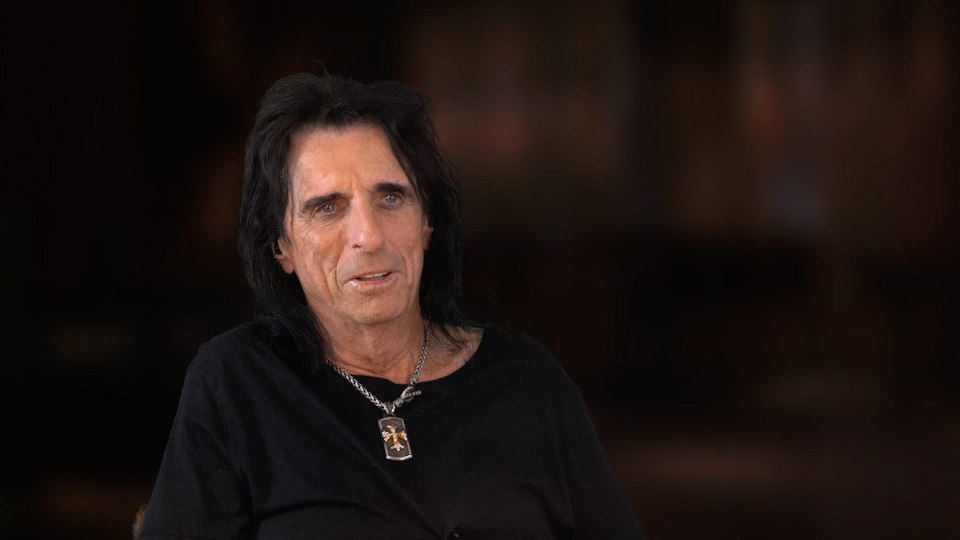

The tension between these two kinds of history is caught when Warhol’s right-hand man Ondine tells Woronov late in life: “If I can’t tell them the simplified version and they can’t imagine the real one – what am I supposed to say?” Alice Cooper anyway does sterling service recalling Max’s first incarnation, where future stars such as Springsteen and Bob Marley were showcased to the industry. The New York Dolls’ “train wreck” Max’s residency is unsentimentally described, as is their slinking back there, having quit a tour due to the lack of good dope in Florida. Dolls manager Marty Thau, one of several interviewees to die during Nightclubbing’s gestation, bitchily derides “this shopkeeper” Malcolm McLaren, who nicked New York’s style for the Pistols.

Alice Cooper anyway does sterling service recalling Max’s first incarnation, where future stars such as Springsteen and Bob Marley were showcased to the industry. The New York Dolls’ “train wreck” Max’s residency is unsentimentally described, as is their slinking back there, having quit a tour due to the lack of good dope in Florida. Dolls manager Marty Thau, one of several interviewees to die during Nightclubbing’s gestation, bitchily derides “this shopkeeper” Malcolm McLaren, who nicked New York’s style for the Pistols.

Max’s closed in December 1974, when first owner Mickey Ruskin’s money ran out. It soon reopened under Tommy Dean, and was hipped to the brewing punk scene by new booker Peter Crowley, an important voice here about the club and music’s pragmatic reality. Johnny Thunders’ smack-wrecked Dolls spin-off the Heartbreakers were, we’re told, a Max’s band. Hilly Cristal’s dogshit-smeared CBGB’s was sanitarily disgusting, and paid bands less. But the Ramones, Television, Blondie and Talking Heads were its bands. Nightclubbing does usefully assert Max’s continuing punk significance alongside CBGB’s, also booking the Ramones and the rest, right up to its closing night in 1981, when the Beastie Boys supported Bad Brains. The owners’ prosecution for allegedly photocopying $100 bills in the basement had colourfully killed the club.

Nightclubbing does usefully assert Max’s continuing punk significance alongside CBGB’s, also booking the Ramones and the rest, right up to its closing night in 1981, when the Beastie Boys supported Bad Brains. The owners’ prosecution for allegedly photocopying $100 bills in the basement had colourfully killed the club.

A supporting cinema short, Sid: The Final Curtain, is more rounded and revealing. Footage of Sid Vicious’ 1978 Max’s residency shows a scratch band including two ex-Dolls playing a post-VU grind while he lankily shouts. “He did his best,” the Stimulators’ Nick Marden allows. “He didn’t kill himself…he hit some notes.” The same band’s Harley Flanagan adds an epitaph for this talentless, 21-year-old star, variously pictured in a Nazi or Texas Chainsaw Massacre shirt, and the scene in which he and Nancy Spungen were somehow sacrificed. “He was a kid…and he wasn’t even a musician. His whole purpose was he was a fuck-up. It was punk rock.”

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

Add comment