The Mauritanian review – moving 9/11 drama | reviews, news & interviews

The Mauritanian review – moving 9/11 drama

The Mauritanian review – moving 9/11 drama

Lawyers for Guantanamo detainee find that justice and the War on Terror don't mix

Whether he’s making documentaries or dramas, director Kevin Macdonald has an eye for the bleak moments in our history, and a dynamic way of recreating them, from the Oscar-winning doc Four Days in September, about the Munich massacre, to the fictionalised account of the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, The Last King of Scotland, which at times played like a horror film.

Compared to those, The Mauritanian feels pretty conventional, a tale of righteous lawyers and their ill-treated client, amid the well-trod US malfeasance in its War on Terror. Yet there’s no denying the almost preternatural humanity of the film’s real-life protagonist and, playing him, a mesmerising, deeply moving performance by French-Algerian Tahar Rahim. Having Jodie Foster along for the ride certainly doesn’t hurt.

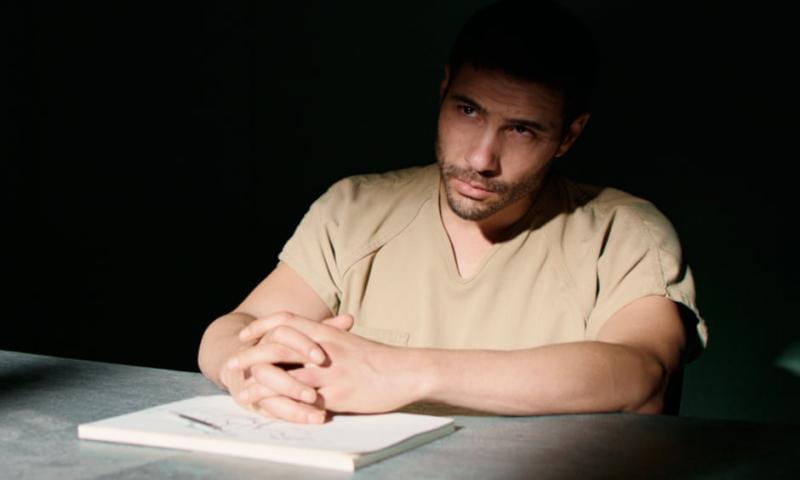

It’s based on Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s best-selling memoir Guantánamo Diary, concerning his rendition from his Mauritanian home two months after 9/11 and years-long imprisonment in America’s notorious detention centre for supposed terrorist suspects, hundreds of people who were never charged.  This focusses on events in 2005, when Slahi’s fate hangs in the balance. On the one hand, he has impressive defence lawyer Nancy Hollander (Foster, pictured above with Shailene Woodley) putting together a case of habeas corpus that, if successful, could lead to his release; on the other, military prosecutor Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch, pictured below), charged with finally trying him as an al-Qaeda recruiter, with the death penalty as the goal.

This focusses on events in 2005, when Slahi’s fate hangs in the balance. On the one hand, he has impressive defence lawyer Nancy Hollander (Foster, pictured above with Shailene Woodley) putting together a case of habeas corpus that, if successful, could lead to his release; on the other, military prosecutor Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch, pictured below), charged with finally trying him as an al-Qaeda recruiter, with the death penalty as the goal.

The script segues between the present, as the lawyers on both sides find it difficult to put together a case when the shady powers that be redact all the evidence, and flashbacks to the “enhanced interrogation”, nay torture of Slahi (waterboarding, sleep deprivation, sexual humiliation) that has given Guantanamo such an appalling reputation.

Macdonald handles the back and forth well, changing his screen ratio and filters to both delineate the transitions and lend the torture sequences an appropriately visceral and nightmarish quality.

Where the film stutters is in the back and forth between the defence and prosecuting teams, which feels rather rote, not least because Slahi’s innocence is never really in doubt, and Couch turns out to be a decent guy whose sense of ‘the rule of law’ prohibits him from accepting the shabby hearsay passed off as evidence by his superiors.  The resulting lack of tension is accompanied by a surprising absence of questioning – the who, why and how on earth did they get away with it that one always wants to throw at this subject, and which was tackled much more forensically in 2019’s Adam Driver starrer The Report. It’s indicative of the degree to which The Mauritanian skirts such nuts and bolts that a shocking twist that draws in the usually unimpeachable Barack Obama has no elaboration whatsoever.

The resulting lack of tension is accompanied by a surprising absence of questioning – the who, why and how on earth did they get away with it that one always wants to throw at this subject, and which was tackled much more forensically in 2019’s Adam Driver starrer The Report. It’s indicative of the degree to which The Mauritanian skirts such nuts and bolts that a shocking twist that draws in the usually unimpeachable Barack Obama has no elaboration whatsoever.

But the focus is clearly Slahi, whose desire and ability to forgive his tormentors (he points out that ‘forgiveness’ and ‘freedom’ are the same word in Arabic) is extremely powerful. Rahim has been consistently impressive ever since he burst onto the scene in Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet in 2009. The past six months have showcased his range, from the chilling, real-life serial killer Charles Sobhraj in the BBC’s The Serpent, even managing to give tight ‘70s trousers an air of menace, to the nuanced turn here that captures Slahi’s goodness, goofball wit and courage without ever forcing pathos. The way he sniffs at a McDonald’s meal his lawyers have brought him, before tossing it away, conveys more indignation and dismay at his confinement than would pages of script.

Foster’s portrayal of Hollander has some of the no-nonsense, hardball confidence of her more morally dubious lawyer in Spike Lee’s brilliant Inside Man (2006), while adding a brittleness that suggests a life of personal sacrifice beneath the tenacity of a woman who’s “been fighting the government since Vietnam.”

The too few scenes between Slahi, Hollander and her more emotional assistant Teri Duncan (Shailene Woodley) are the film’s highpoints, alongside some nicely restrained heavyweight sparring between Foster and Cumberbatch, who’s also a producer on the film.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Blu-Ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-Ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Add comment