Dave Eggers: The Monk of Mokha review - how to become a grand master of coffee | reviews, news & interviews

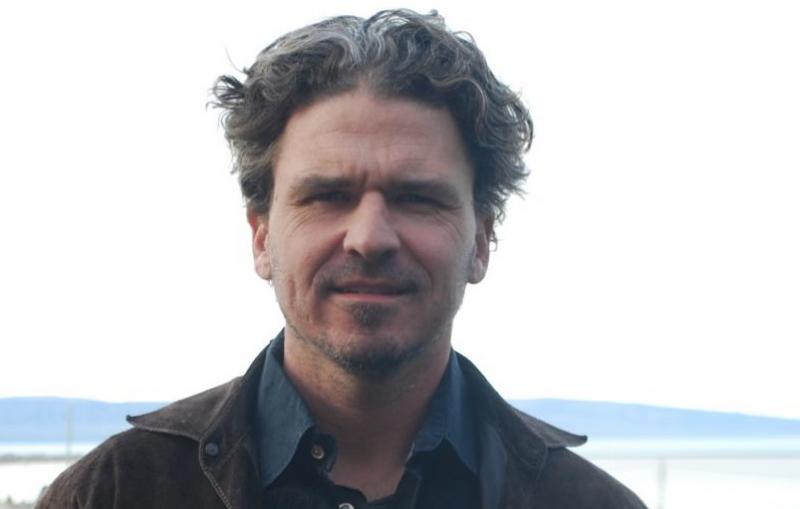

Dave Eggers: The Monk of Mokha review - how to become a grand master of coffee

Dave Eggers: The Monk of Mokha review - how to become a grand master of coffee

The true story of a young Yemeni-American and his American dream

A macchiato may never taste the same again. If you’ve ever wondered about the politics and history behind your cup of designer coffee, The Monk of Mokha will answer all your questions, and more.

This is the prolific Dave Eggers’s third semi-biographical work: What is the What tells the story of one of Sudan’s “lost boys” and his journey to America; Zeitoun is the dramatic story of a Syrian American survivor of hurricane Katrina. In both of these works of reportage, Eggers gets close to his subjects and exposes trauma, injustice and prejudice. And both are page-turners, just as many of his novels are – The Circle, A Hologram for the King, even the rather disappointing Heroes of the Frontier.

The Monk of Mokha is another true story, though somehow less absorbing: that of Mokhtar Alkhanshali, a young Yemeni-American, born in Brooklyn and raised in San Francisco in a one-bedroom apartment shared with his parents and seven siblings in the seedy Tenderloin district, who takes on, with no experience, the task of resuscitating the Yemeni coffee industry. And this has special significance in the light of Trump’s Muslim ban, which includes Yemen. “I hope they have wifi in the camps,” Mokhtar jokes grimly to Eggers after the election.

Eggers, who had no interest in speciality coffee before this, spent the requisite hundreds of hours with him over the course of three years and travelled to Yemen, Ethiopia and other places with him to visit coffee farms, but there is a somewhat removed feel to parts of the narrative, as if too much is being left out. The cast of minor characters is too big and sometimes the details of coffee picking, milling, grading and roasting start to pall (though who knew that Rimbaud was a coffee trader in Harat, Ethopia for a while, or that civet coffee is made from beans taken from the faeces of a civet after they’ve been processed by its digestive system?).

Mokhtar, a charmer but prone to bad luck – the book starts with him losing a satchel containing a brand-new laptop and $3,000 in cash – has never managed to stick at anything for long, though he’s good at absorbing vast amounts of information. After leaving school he works at a series of jobs: as a salesman at Banana Republic, where he learns to dress like a preppy Rupert Bear; at the shoe department of Macy’s, where he dates rich women and soon sounds knowledgeable about expensive vacations he could never afford; as a sizzling hot Honda salesman and, after the briefcase set-back, as lobby ambassador, i.e. doorman, at a swanky apartment building called the Infinity.

Then coffee enters his life in the shape of a statue of a Yemeni man drinking a cup of coffee opposite the Infinity. Mokhtar, who spent time in Yemen with his grandparents, sent by his parents to straighten him out when he was a truanting teen, immerses himself in the history of the bean and discovers that it was first brewed by a Sufi holy man (the monk in question) in Mokha, a port city in Yemen, a country now better known for terrorism and drone strikes. The Yemeni coffee industry is more or less decimated, with Ethiopia having taken over in the region. Qat is now the number one crop in Yemen. So Mokhtar (a friend who advises him on his unimpressive business plan rightly says of its title, “Who was the monk? Was Mokhtar the monk? Why?”) sets out on a quixotic attempt to restore Yemeni coffee to world prominence. This entails a massive learning curve for him and for the reader, sometimes too much of one.

Then coffee enters his life in the shape of a statue of a Yemeni man drinking a cup of coffee opposite the Infinity. Mokhtar, who spent time in Yemen with his grandparents, sent by his parents to straighten him out when he was a truanting teen, immerses himself in the history of the bean and discovers that it was first brewed by a Sufi holy man (the monk in question) in Mokha, a port city in Yemen, a country now better known for terrorism and drone strikes. The Yemeni coffee industry is more or less decimated, with Ethiopia having taken over in the region. Qat is now the number one crop in Yemen. So Mokhtar (a friend who advises him on his unimpressive business plan rightly says of its title, “Who was the monk? Was Mokhtar the monk? Why?”) sets out on a quixotic attempt to restore Yemeni coffee to world prominence. This entails a massive learning curve for him and for the reader, sometimes too much of one.

We learn how coffee seedlings from the Yemen were stolen by the Dutch in 1616, then given to France, then smuggled by the Portuguese to Brazil; how beans must only be picked when cherry-red, the colour of Mokhtar’s ring; what makes a defective bean; the evils of commodity pricing; and that the Q grading test, which he fails twice, is an extremely difficult but necessary part of being an expert on arabica coffee. Mokhtar has to shell out thousands of dollars, mostly borrowed from an extraordinarily long-suffering businessman called Omar, in order to take lessons at the Blue Bottle coffee headquarters in Oakland, then to go to Ibb in Yemen to doss down on his relatives’ floor, meet farmers all over the country, con them into thinking he’s an important exporter, explain to them how he can empower them and get them better prices, teach them how to pick their beans, collect samples and get them back to the US. Phew.

Over three years, in spite of many setbacks including a thrillingly tense episode when he’s kidnapped and almost killed as the civil war rages, Isis takes hold and Saudi bombs rain down, Mokhtar remains extraordinarily focused, gets his business into gear and his beans back home. The rest is coffee history: the beans are of the highest quality and Port of Mokha coffee (the monk moniker is gone) is a sell-out even at $16 a cup, the most expensive coffee Blue Bottle ever sold (the price is falling as supplies increase). It’s an American dream, as Eggers says, all about entrepreneurial zeal and creating indispensable bridges between the developed and developing worlds, between nations that produce and those that consume. And that’s a hell of a success story. Yet it’s a little too cumbersome and top-heavy. We learn a lot about coffee but in the end Mokhtar himself remains elusive.

- The Monk of Mokha by Dave Eggers (Hamish Hamilton, £18.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment