Seasons of love: Rent 20 years on | reviews, news & interviews

Seasons of love: Rent 20 years on

Seasons of love: Rent 20 years on

Jonathan Larson died before his musical struck gold. Was there more to come?

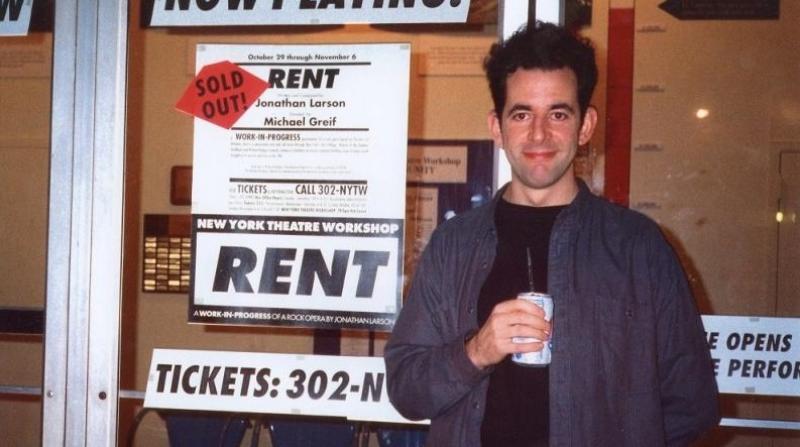

On January 25 1996, after Rent's final dress rehearsal at the off-off-Broadway New York Theater Workshop, its composer Jonathan Larson went home to his scuzzy loft round the corner, switched on the electric kettle and, before the water had boiled, keeled over with an aortic aneurism. Later that night his roommate found his body on the floor of the kitchen.

So Larson did not witness the remarkable impact of a show which reached out to the Generation X-ers whose grungy tastes musical theatre usually disdains to address. Rent is set in the East Village, and its cast of characters are the kind of crowd Larson hung out with in the seven years it took to create - drug addicts, transvestites, penniless bohemians of every sexual persuasion, miscellaneous arty wannabes infected with AIDS and/or ambition.

The first public performance of Rent was postponed in favour of a private recital for friends and family. When the show opened for business, New York's crack troop of make-or-break critics praised it to the heavens. Comparisons were invoked with other mouldbreaking shows - Hair, the hit musical for the flower people, and A Chorus Line, with which it shares one striking motif. For one of the key songs, the entire cast lines up downstage in a face-off with the audience. (Pictured below: the 20th anniversary touring cast of Rent)

Rent duly sold out its five-week run in 24 hours. Tickets for a month-long extension went the same way by the end of the week. Those early audiences found a dense concentration of stellar entertainers - from Whitney Houston to Al Pacino - being entertained by a cast of unknown actors on $305 a week. Or "$5 more than unemployment," as one cast member remarked. Some had no previous acting experience. One of the male leads had sung in a heavy metal band that failed to get a record deal. Within three months, the show was up and running on Broadway. Twenty-one television crews witnessed the opening night. Larson died at the age of 35, as fulfilled as he had ever been but ignorant of his own triumph - the bounty of posthumous Tonys, Obies, Critics Circle and Drama Desk awards that his show would soon harvest.

Rent duly sold out its five-week run in 24 hours. Tickets for a month-long extension went the same way by the end of the week. Those early audiences found a dense concentration of stellar entertainers - from Whitney Houston to Al Pacino - being entertained by a cast of unknown actors on $305 a week. Or "$5 more than unemployment," as one cast member remarked. Some had no previous acting experience. One of the male leads had sung in a heavy metal band that failed to get a record deal. Within three months, the show was up and running on Broadway. Twenty-one television crews witnessed the opening night. Larson died at the age of 35, as fulfilled as he had ever been but ignorant of his own triumph - the bounty of posthumous Tonys, Obies, Critics Circle and Drama Desk awards that his show would soon harvest.

Twelve years later, the Broadway production of Rent finally closed after 5,123 performances and the "Rentheads", as its diehard fans who saw the show countless times and sang along to its 31 songs, finally dispersed.

In the years Larson was still waiting tables in Greenwich Village, writing the odd tune for Sesame Street and a couple of small-scale musicals, some important people believed in him. One of his patrons was Stephen Sondheim, who admired Larson's bold attempt to remarry the two parties which had had a messy divorce some time in the 1940s: popular music and theatre. Sondheim says that "he was on his way to finding a real synthesis". It was Sondheim who was jury chairman of the award panel which secured Larson the grant to mount a seven-night workshop run of Rent in 1994. During the interval on the first night, a producer put up $250,000 to fund a full production. (Pictured below: Layton Williams as Angel)

Rent belongs to that oxymoronic genre, the rock opera. Indeed no musical has ever fitted the category more snugly. Yes, the orchestration comes from a fully electrified band, but this frotting paean to the bleach-haired denizens of downtown hip could not have a more elitist, high-art template. Rent is basically an update of La Bohème. In a freakish coincidence, it actually opened a century almost to the day after Puccini's opera had its premiere in Turin.

Rent belongs to that oxymoronic genre, the rock opera. Indeed no musical has ever fitted the category more snugly. Yes, the orchestration comes from a fully electrified band, but this frotting paean to the bleach-haired denizens of downtown hip could not have a more elitist, high-art template. Rent is basically an update of La Bohème. In a freakish coincidence, it actually opened a century almost to the day after Puccini's opera had its premiere in Turin.

Larson had encountered the opera in a puppet version during his affluent, middle-class childhood in suburban New York State. But he was not the first to spot the parallel between La Bohème's portrait of tubercular artists and courtesans on the Left Bank and the community of diseased dreamers he lived among in the East Village. When it was pointed out to him by a lyricist he was working with, he even dug beyond the opera to Henri Murger's autobiographical short stories of Parisian low life which form the basis of the libretto.

Rent's six main characters have an uninterrupted line to Puccini. The poet Rodolfo becomes rock composer Roger, an HIV-positive ex-junkie whose ambition is to write one great song before he dies. He lives with video artist Mark Cohen, updated from the painter Marcello. Roger's girlfriend, as in the opera, is called Mimi, only now she's a dancer in an S&M club. Puccini's Mimi has TB; Larson's is HIV-positive. As in the opera, they first meet when she needs a light for her candle. There's even a song called “La Vie Bohème”.

Beyond the odd death, and sundry lovers' tiffs, there's not much to the plot. If Larson had had his way it would have been much more gooey and self-congratulatory than it actually is. He once said to a roommate, "Did you know that this ZIP code has the second highest AIDS rate in the country?" Mimi and Roger break into romantic song when their bleepers go off at the same time, reminding them to take their AZT. (Pictured below: Philippa Stefani as Mimi and Ross Hunter as Roger)

As it celebrates its 20th anniversary, one great imponderable can never be answered. Was Larson the great white hope of Broadway? Or had he already given the musical his best shot? In the world of pop, death is seen as a smart career move, and it may well be that the axiom applied to Larson. Its original director Michael Greif claimed that "30 years of great theatre have been lost." In Broadway Babies Say Goodnight, Mark Steyn adjudged, "Not many musicals are the creation of a lone individual in book, lyrics and music, and, when they are, it's usually because that's the only subject the guy knows how to write. Rent feels as if Larson poured everything he had into it: it was his world, the only world he knew."

As it celebrates its 20th anniversary, one great imponderable can never be answered. Was Larson the great white hope of Broadway? Or had he already given the musical his best shot? In the world of pop, death is seen as a smart career move, and it may well be that the axiom applied to Larson. Its original director Michael Greif claimed that "30 years of great theatre have been lost." In Broadway Babies Say Goodnight, Mark Steyn adjudged, "Not many musicals are the creation of a lone individual in book, lyrics and music, and, when they are, it's usually because that's the only subject the guy knows how to write. Rent feels as if Larson poured everything he had into it: it was his world, the only world he knew."

Larson gave his last interview - to the New York Times - a couple of hours before his end. The dress rehearsal was just over, the theatre was full of noise, and so he and the journalist talked in the theatre's cramped but secluded box office. It was a weirdly suitable venue, given that the interviewee's death became a licence to print money. Rent, about achieving your artistic potential before the grim reaper comes a-reaping, still looks like a self-fulfilling prophecy. Like the Mozart of Amadeus, Larson couldn't know that what he was actually composing was his own requiem.

- Rent at St James Theatre until 28 January, 2017 then touring until 27 May

- theartsdesk recommends the best musicals in London

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment