Nikolai Astrup: Painting Norway, Dulwich Picture Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Nikolai Astrup: Painting Norway, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Nikolai Astrup: Painting Norway, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Primal and domestic mingle in passionate homage to the Norwegian landscape

Dulwich Picture Gallery, the oldest public painting gallery anywhere with one of the world’s finest collections of Old Masters, has in recent years built up a deserved reputation for bringing to the British audience unfamiliar aspects of well known painters, along with reappraisals and new discoveries. Their latest show is the first-ever exhibition outside of Norway for that country's landscape painter Nikolai Astrup (1880-1928).

The son of an ascetic Lutheran pastor, Astrup was sickly even as a child, living in a damp and cold wooden parsonage in a rigorous climate. Often bedridden, the young boy took solace in looking out of his windows at the magnificent landscape of mountains, farmland and water that surrounded his village, Ålesund, on the west coast of Norway (pictured below right: Marsh Marigold Night, c.1915). He was determined to be an artist and his tenacity triumphed over severe paternal opposition. He was to spend almost all his life in straitened financial circumstances in spite of some success as an artist, with exhibitions in Oslo and Bergen, but his health was always uncertain and he died of pneumonia when 47.

Even so, he had rather shockingly married Engel, who turned out to be a wonderful craftswoman, when she was only 15 and they had eight children in 14 years. The work of major Norwegian writers and composers has of course travelled: think Ibsen, adored and performed everywhere, and Grieg. Yet in painting only Munch has an overwhelming international reputation, although visits to the National Gallery in Oslo and to the many small museums in Norway reveal several visual artists well worth looking at beyond their geographical framework. Astrup is a vivid example, an experimental and dazzling printmaker, and a painter of memorable landscapes, as well as a photographer (he used photographs as an aide memoire). His photographs on view show us the scenes he saw, but also indicate their transformations in print and paint.

Even so, he had rather shockingly married Engel, who turned out to be a wonderful craftswoman, when she was only 15 and they had eight children in 14 years. The work of major Norwegian writers and composers has of course travelled: think Ibsen, adored and performed everywhere, and Grieg. Yet in painting only Munch has an overwhelming international reputation, although visits to the National Gallery in Oslo and to the many small museums in Norway reveal several visual artists well worth looking at beyond their geographical framework. Astrup is a vivid example, an experimental and dazzling printmaker, and a painter of memorable landscapes, as well as a photographer (he used photographs as an aide memoire). His photographs on view show us the scenes he saw, but also indicate their transformations in print and paint.

Astrup concentrated exclusively on the environment in which he was born, brought up and lived almost all his life. There was a brief interlude when, painfully poor, he went to art school in Kristiania (as Oslo was called from 1877 to 1925), studying with the remarkable Harriet Becker, and later Christian Krohg in Paris, both of whom should also be better known. Admired by his peers and teachers, Astrup won awards and scholarships and travelled to Paris, Berlin and London; he was very impressed by the enthusiastic autodidact, Henri Rousseau. He named his first born son Arnold Böcklin after the Swiss painter much given to mythological scenes (most famously Isle of the Dead, 1880-86) and Japanese prints which influenced his own. He was certainly in the zeitgeist, but his tenacious personality resulted in an unusual attachment to home and family.

Travelling brought home into sharp focus. He remained wholly absorbed in the surroundings in which he was brought up, and in which he was to live his life – the world seen not in a grain of sand but in a vast and barely tamed wilderness.

There is awe, wonder, delight and plain unpretentious enjoyment

The landscape in the Jølster region, with its lakes, mountains and fjords, is brooding and magnificent, awesome in its vistas and extremes of weather and light. It is also refined by smallholdings, beautifully organised gardens, wooden houses with grassy roofs, and Astrup was particularly entranced by the golden cascades of marsh marigolds (although as they flourish in poor conditions, they were already doomed by increasingly effective farming methods). It was a small society, dominated and punctuated by the weather, the seasons and its ceremonies; there were moments to socialise in the domestic gardens, the local funeral processions when need be, and what Astrup called his still-life interiors.

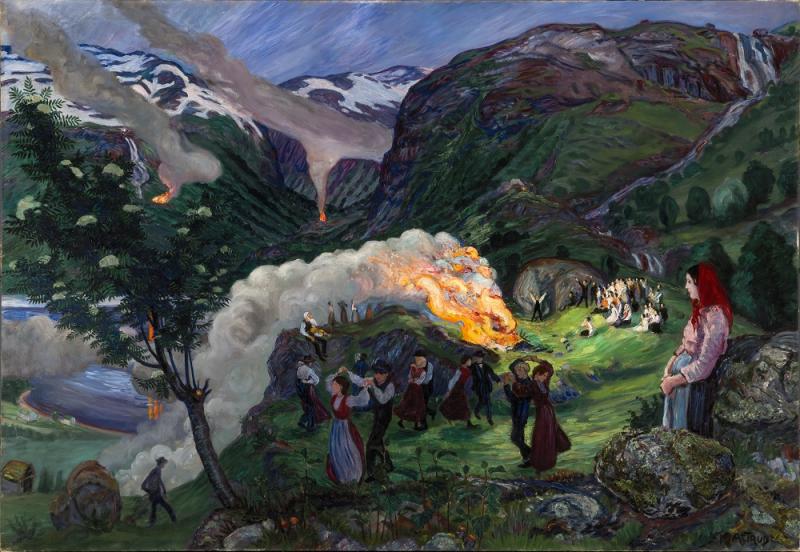

Here are lives narrated in objects, with affecting arrangements of dining-table and fruit bowls, Christmas decorations, home-designed and -made hangings and tablecloths, simple rustic furniture and windows with views. His family home, a farm and various buildings on a steep hillside, Sandalstrand, now known as Astruptunet, is preserved in his honour. And subversively thrilling in a remnant from pagan times, much disapproved of by Astrup’s father, Astrup described in his own inimitable and vivid way with paint the midsummer firelit revels in the strange light of the midnight sun (main picture: Midsummer Eve Bonfire, before 1915). This is perhaps the extreme example of what irradiates all of Astrup’s subject matter – the everyday illuminated by the mystic and the mythic, the particular made universal.

It is also clear how tough it was; in this period Norway was hardly rich, and almost exclusively agrarian, and the Jølster region with its precipitous, even vertiginous rocky hills, and thin soil, was hardly the best farming country. The subject matter itself contributes perhaps to Astrup’s almost heroic stature in his own country, his work beloved and on view in all the major national collections yet almost totally unknown – except to specialists – outside Norway.

Responsive to the past and to narrative tales, Astrup could, consciously or not, anthropomorphise the landscape. In prints and paintings such as Spring Night and Willow (1917/after 1920), or A Morning in March, c.1920 (pictured left), the tree has become a female creature with huge hands stretching upwards into the sky, perhaps in worship or homage. His photographs show us that this unusual tree by the water existed.

Responsive to the past and to narrative tales, Astrup could, consciously or not, anthropomorphise the landscape. In prints and paintings such as Spring Night and Willow (1917/after 1920), or A Morning in March, c.1920 (pictured left), the tree has become a female creature with huge hands stretching upwards into the sky, perhaps in worship or homage. His photographs show us that this unusual tree by the water existed.

Astrup responded acutely to the emotions evoked by the scenes he depicted: there is awe, wonder, delight and plain unpretentious enjoyment, and for all his care he communicates too a primitive directness. The woodblocks over which he laboured might be used several times, but each resulting image even if of the same view, was individually worked over again, making each print a one-off, a monotype, richly coloured and textured.

In both the titivated, manipulated woodcuts and the richly worked-over paintings, colours are resonant although not melodramatic, and everything, far and near, is precisely shown. There is no fading away into the distance, but a passion for clarity. Rainbows, trolls, the trunks of birch trees in all their variegated, peeling-layered bark; foxgloves, muddy paths in the woods, rainbows, the farmyard birds, haystacks, the kitchen garden: all seem perhaps mundane subjects. But the lavish care, close scrutiny and attention that the artist pays his surroundings is a kind of passionate homage to the mingling of natural and man-made beauty.

It is riveting to see his paintings close up, with their extraordinarily varied brushstrokes, and tender explorations of the most subtle colours: in some mysterious way he shows us, scene by scene, the play of light through time. Whether major minor master, or minor major master, it hardly matters: special, unmissable, and – yes – although of his time, unique.

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Comments

I was seduced by Astrup's

I was seduced by Astrup's pictures in a wing of one of the KODE museums in Bergen, and wondered why we didn't (then) know about him over here. The newish Astrup room there makes a fine permanent exhibition space, and the various art galleries would make a trip to Bergen worthwhile in itself - though of course there's much more to it, not least one of the most romantic harbours anywhere.

I love your line about 'the play of light through time', and understand what you mean.