Berlinale 2014: Cathedrals of Culture | reviews, news & interviews

Berlinale 2014: Cathedrals of Culture

Berlinale 2014: Cathedrals of Culture

'Genius loci': the souls of six buildings caught by six directors, in 3D

Back at the Venice Biennale in 2010, the German film director Wim Wenders showed a 3D video installation titled “If Buildings Could Talk”.

Exploring the theme of how architecture interacts with human beings, and attempting to capture the soul of the buildings themselves, he wrote a poem on the subject with the lines: “Some would just whisper,/ some would loudly sing their own praises,/ while others would modestly mumble a few words/ and really have nothing to say.”

It was an idea that obviously came to fascinate Wenders, and he has been integral in the process of expanding it into Cathedrals of Culture, a series of six documentary films shot in 3D by different directors that premiered as part of this year’s Berlinale. (Wenders’s own absence from the presentation – he was away filming in Canada, where shooting schedules apparently depended heavily on snow coverage, and thus precluded even a brief return to Berlin – felt strange, as if a parent was missing at a christening). Wenders himself chose a building from his native city, the Berlin Philharmonic (pictured, below left: "an unsinkable Titanic of concert halls"), built by Hans Scharoun in 1961, that for many years stood almost alone on the periphery of the Western sector, right next to the Berlin Wall which appeared in the same year.

Other participants covered locations less directly related to our "traditional" concept of culture and eminence in architecture. Austria’s Michael Glawogger took the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg, a cavernous and humanly empty building of echoing book stacks – not a computer in sight – and presented it with over-voice lines drawn from the writings of a range of Russian writers, from Gogol to Joseph Brodsky, as if the building spoke the literature in which it is seeped. Danish director Michael Madsen selected Norway’s Halden top security but renowned "humane" prison, accompanied by a narrative voice spoken by the prison's psychologist ("I think my job is needed"; "I don't know life outside"). Those two, different kinds of "cathedrals", stressed environment and atmosphere over feats of building.

Other participants covered locations less directly related to our "traditional" concept of culture and eminence in architecture. Austria’s Michael Glawogger took the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg, a cavernous and humanly empty building of echoing book stacks – not a computer in sight – and presented it with over-voice lines drawn from the writings of a range of Russian writers, from Gogol to Joseph Brodsky, as if the building spoke the literature in which it is seeped. Danish director Michael Madsen selected Norway’s Halden top security but renowned "humane" prison, accompanied by a narrative voice spoken by the prison's psychologist ("I think my job is needed"; "I don't know life outside"). Those two, different kinds of "cathedrals", stressed environment and atmosphere over feats of building.

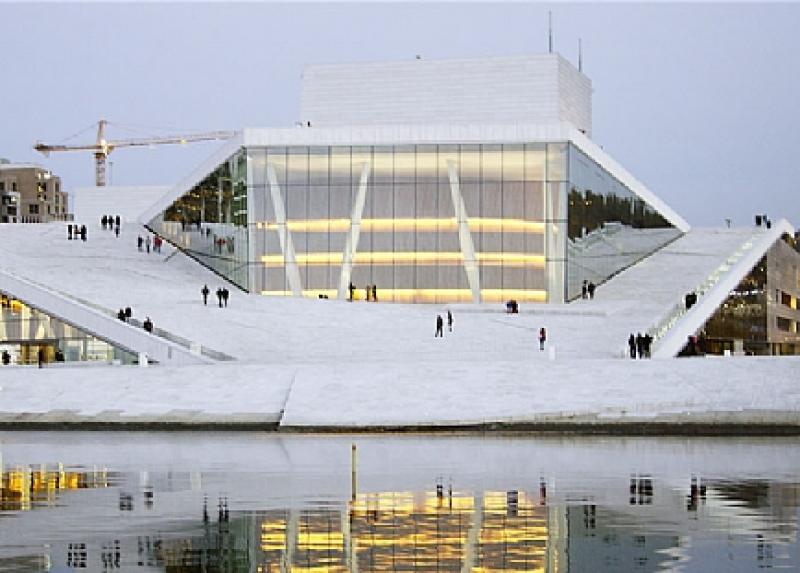

Robert Redford went back to the issue of just what an inspired architect can create, accompanying his vision of the Salk Institute, a centre of scientific excellence in La Jolla, California built by Louis I Kahn, with the voices of some of the scientists for whom it has become a creative home (as well as a compelling musical score by Moby). The final two segments returned closer to what we might traditionally expect as tributes to cultural spaces: the segment from Norway's Margreth Olin dedicated to Oslo’s opera house was something like a love poem to the building, the work of the local architecture firm Snøhetta. Brazilian director Karim Ainouz went inside the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the in-its-time shocker (pictured, below right: "oil refinery, or giant climbing frame") from Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano that has mellowed into the Paris skyline since its 1977 opening.

it's a very democratic endeavour, one that encourages us all to look around again at our surroundings

Cathedrals of Culture became a rather wonderful mélange, where the smallest details – the characters of those who work behind the scenes, or the architects, like the Berlin Phil's Scharoun, who's brought back to life to wander the space he created – spoke richly. Sometimes the 3D effects were spectacular, and seemed completely integral to the result (most impressively perhaps when Wenders caught Simon Rattle rehearsing with the Berlin Phil: no surprise given the director's remarkable achievements with 3D on his ballet film Pina), and they'll repay being watched in any future cinema screening. At other times they don’t seem so essential, and thus will work fine with any subsequent section-by-section broadcast on television.

Every viewer will find his or her own favourites. Mine included the stark, icy beauty of the Oslo Opera House, dominating the city’s waterfront; the old ladies who slowly wander the corridors and stacks in the Russian National Library, which seems to exist out of time; and the Salk Institute, a miraculous space set on the edge of the ocean in rough countryside that was consciously created as a fulcrum for scientific ideas.

Every viewer will find his or her own favourites. Mine included the stark, icy beauty of the Oslo Opera House, dominating the city’s waterfront; the old ladies who slowly wander the corridors and stacks in the Russian National Library, which seems to exist out of time; and the Salk Institute, a miraculous space set on the edge of the ocean in rough countryside that was consciously created as a fulcrum for scientific ideas.

You might think this was a high culture concept destined for an elite (and it will certainly be appreciated as such). In fact, in the process of its development it's become something else as well, a rather more democratic endeavour: one that encourages us all to look again at our surroundings, and appreciate the depths of human history and culture (in the broadest sense) that are so deeply contained in the spaces in which we live, and through which we move.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment