Sonica, Glasgow | reviews, news & interviews

Sonica, Glasgow

Sonica, Glasgow

You want to know what the future of music looks like? Read on

At first it looked like a joke. But, as each muscle spasm, set off by an electric shock, did appear to produce a pained expression in the performer and a subsequent note, one slowly had to accept that these four string quartet players were indeed being electrocuted into performance. The Wigmore Hall, it wasn’t. Sonica, it certainly was.

This was the second year of the four-day festival that, each November, takes over Glasgow's galleries, theatres, warehouses and shop windows and runs amok, stretching the meaning of music to its artistic, intellectual and technological limits. Cross-pollination is everything. This year we had a musical lunch, a sonically composed walk and an aural experience that was mainly being transmitted through our feet. Some of the experiments fell flat, several triumphed.

The festival opened with a set from Norwegian vocalist Maja S K Ratkje, who delivered a blistering VJ-accompanied improvisation at last year’s Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (HCMF). There was an attractive synergy between HC Gilje’s LED video that flowed across 18 screens and Ratkje’s sophisticated electronically-underpinned improvisation, order emerging out of chaos (see picture below). A splash of the crotales, or a sliver of a whistle, would become a pulse; a screen of lines might become a cross-hatch. The epiphanic heights of HCMF weren't quite achieved this time. This was a more subtle show, a music box rising up from the sonic detritus that Ratkje had gathered together.

Even a composition based on electrocuting your players requires interesting musical ideas

It wasn’t the only transfer from HCMF to appear at Sonica. They share an artistic director in Graham Mackenzie. Cathie Boyd and Patrick Dickie complete the top team. Yannis Kyriakides’s The Buffer Zone, which premiered in Huddersfield in 2005, is an opera woven from the sonic scraps of daily life accrued by a bored Cypriot border guard. Whistling, humming, the mantra of the walk-talkie ("over-and-out"): Kyriakides knitted these fragments of tedium to some composed music for piano and cello, who played either side of a screen, watched over by the sentry, Tido Visser. The work, unfortunately, never transcended its source material and we never transcended the tedium.

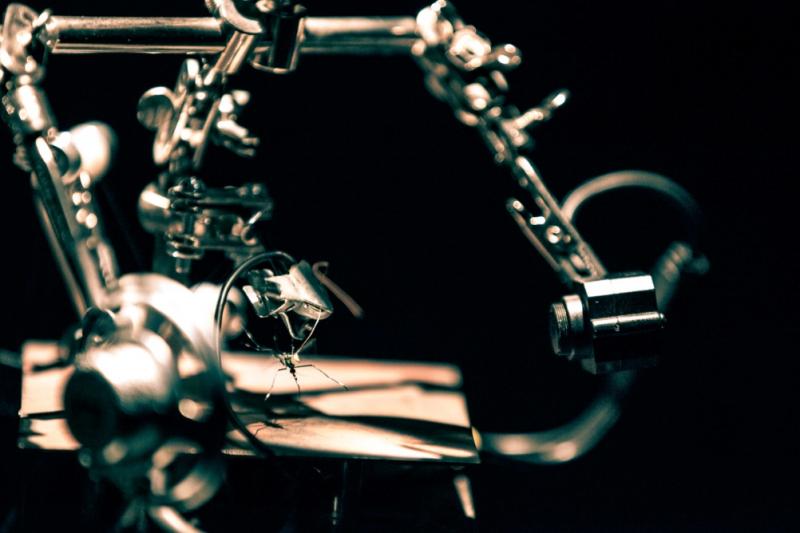

Risk-taking of a special kind greeted us at the CCA gallery. At one end of a room we could see and hear the hum of three mosquitoes, who'd been stuck to the spot with hot wax and on whom were being encouraged to breath. Carbon dioxide, apparently, excites mosquitoes. Their consequent movements were being filmed and projected onto the walls. At the other end of the room, artists Robin Meier and Ali Momeni were tending to the substitute mosquitoes, feeding them sugar water, keeping them alive, for their turn to come.

Believing the computer-generated Indian drone piped out over speakers to be a possible mate, the three male mosquitoes were buzzing back in sympathy and attempted synchronisation. What filled the room, then, was an extraordinary love song and, more abstractly, a sensational piece of Niblock-ian drone art.

Believing the computer-generated Indian drone piped out over speakers to be a possible mate, the three male mosquitoes were buzzing back in sympathy and attempted synchronisation. What filled the room, then, was an extraordinary love song and, more abstractly, a sensational piece of Niblock-ian drone art.

Not all hybridisation ended up in such sophisticated territory. The other show at the CCA Raydale Dower’s The Eye of the Duck, built on promising foundations, recreating the memorable Red Room from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, under-delivered. As, sadly, did Michael Davies’s Compositions for Involuntary Strings, the night the string quartet was tortured at the Tramway.

The underlying principles were interesting. Davies had composed her works so that they would produce a series of electric shocks, which would force certain muscles of each wired-up musician to expand or contract and induce them to make an involuntary sound from their instrument. Even a composition based on electrocuting your players, however, requires interesting musical ideas. And Davies didn’t provide us with enough in this respect. The best parts were the least serious, especially in the third movement of FM2030, when the spasming resulted in crazed, non-musical salutes and sweeps of the arm.

The off-piste explorations are as important as the theatre-bound ones at Sonica. Braving the rain and cold always brought rewards. Exploring Sven Werner’s world was as ever intriguing. We were invited this year to his studio above a fishmongers where each hour a performance would be struck up on one of his dilapidated instruments.

I caught one: an extraordinary duet, in which the bare strings of two naked pianos were being sounded using loose bow hairs and hammers, a Charlemagne Palestine-like cloud of chordal sound emanating into the room. There is a certain tweeness to Werner’s Victoriana-obsessed aesthetic (which will see him hiding a projector in a battered old suitcase) but you can’t gainsay his imagination.

A certain Alice in Wonderland tweeness carried over into the Lunchbox “adventure” from Josh Armstrong, with its packages of food and drink and instructions labelled “eat me”, “drink me”, “pick me”, “read me” etc. The words were encouragingly poetic, as was the weather, but the idea that I was going to create a theatrical performance out of my food rather than just eat it (and wonder if it was any good - which it wasn't) was always going to be a bit optimistic.

Of the ambulatory commissions, the best was Rob van Rijswijk and Jeroen Strijbos’s Walk With Me piece that, using an iphone map to morph the music as we walked, scored the entire city in various luminous and cloudy washes of electronic and acousmatic sound. Highlights included the jungle of noise that appeared as we crossed one of Glasgow’s major arteries and the Susan Stenger-like consonant revelation at the Kelvingrove Park fountain.

The Picture Window series, co-curated by Annie Crabtree and Eileen Daily, one of the outstanding moments of last year’s Sonica, proved fascinating again. Not all of it was ready for the start of the festival but the best installation was. All Eyes Wide saw artists Edward Crawley and video artist Jamie Wardrop take over a shop in the centre of Glasgow and transform it into a vast, imaginary sonic playground. Blindfolded and headphoned, we wandered around the space barefoot, the floor and music changing in texture and warmth. A man took our hand, offered us objects and delivered a world-weary narrative of 20-something life. Beautifully executed and powerfully imagined, this was one of the stand-out works of the festival.

Sonica is a generous place. Risks are taken but fun is had, too. Which other new-music festival would ferry us out-of-town to a warehouse and offer us, alongside some intensely memorable and seriously playful free improv from Giles Perring, a light show centred around an Elvis tribute act and a flying, blow-up fish?

Don't be fooled. Sonica is no circus. This is the future of contemporary music. Those who have even the slightest interest in what happens next should make sure they catch it.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment