George Catlin: American Indian Portraits, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

George Catlin: American Indian Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

George Catlin: American Indian Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

A series of mesmerising images from the 19th century of the native peoples of North America

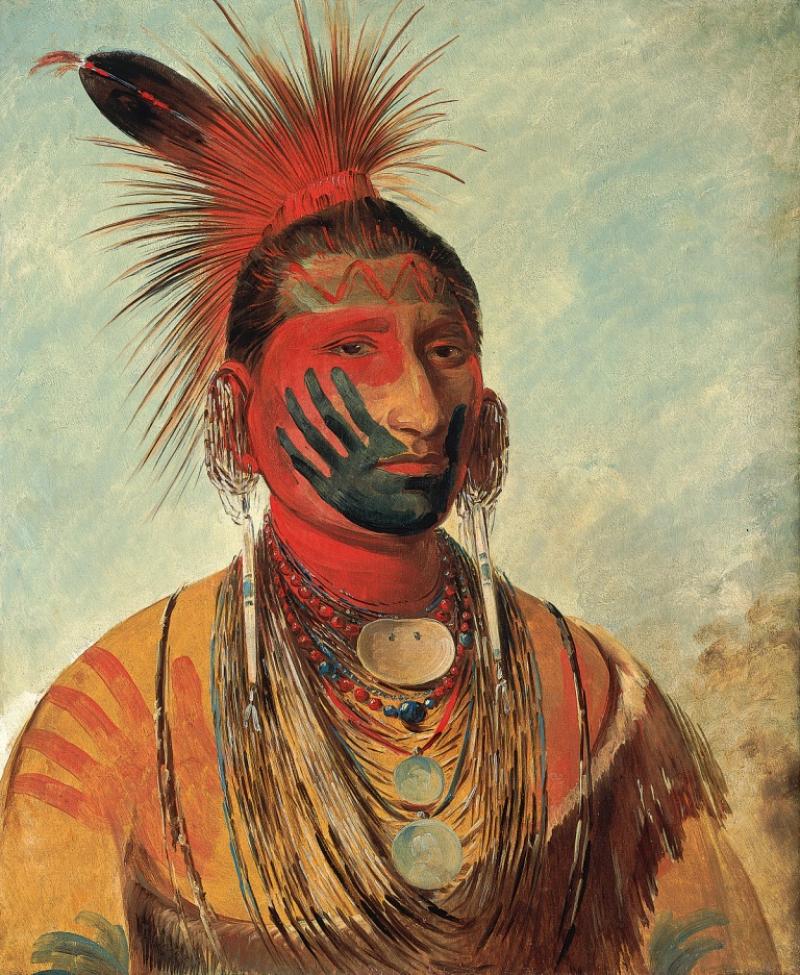

Scores of reddish-bronze skinned men, and a few women and children, in full regalia, festooned in face paint, feathers, jewellery and decorations of all kind. They stare out at us, impassive and imperturbable, immortalised by George Catlin (1796-1872), the most famous American artist you have never heard of.

His work is embedded in the American consciousness, if not its conscience. This succinct and representative selection visits London 170 years after the sensational exhibition of his Indian Gallery in the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly in 1843, when 500 of his portraits of American Indians were stacked from floor to ceiling. Catlin, an entrepreneurial showman with, alas, no business sense, provided an experience of total immersion, complementing his paintings with a selection of his seminal collection of artefacts, from weapons to costumes. Groups from the Iowa and Ojibwa tribes demonstrated their rituals and dances; he later showed Indian costume, if not actual Indians, at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

It was in Philadelphia while studying painting after a brief career as a lawyer that Catlin saw a delegation of American Indians and was inspired to his life's work: to record in paint as many tribes as he could visit, mostly west of the Mississippi, where all too many had been sent when President Andrew Jackson cleared the eastern states.(Pictured right, Eeh-nís-kim, Crystal Stone, Wife of the Chief Blackfoot/Kainai, 1832).

It was in Philadelphia while studying painting after a brief career as a lawyer that Catlin saw a delegation of American Indians and was inspired to his life's work: to record in paint as many tribes as he could visit, mostly west of the Mississippi, where all too many had been sent when President Andrew Jackson cleared the eastern states.(Pictured right, Eeh-nís-kim, Crystal Stone, Wife of the Chief Blackfoot/Kainai, 1832).

It does not matter that his subject is greater than his talents, for he is more than adequate in his meticulous attention to the detail of costume - leggings, moccasins, face paint and make-up - as well as the accessories, from jewellery of all kinds to bows and arrows, feathered headdresses, necklaces of bear claws and lacrosse sticks. These dignified renderings of remarkable peoples from the Indian nations – Lakota, Sioux, Pawnee, Osage, Blackfoot, Sac, Fox, Arikara, Choctaw, Seminole to name but few – are intensely memorable. Catlin’s lack of sophisticated visual polish has worked to our advantage: he was absolutely determined to paint his chosen individuals in his own words as “true and facsimile traces of individual and historical facts”. To this end he also painted ball games, buffalo hunts – a memorable portrait depicts a single wounded buffalo dripping blood and swaying slowly to the rhythm of his approaching death - and medicine men, and recorded one of the last coming of age ceremonies of the Mandans in North Dakota.

The extraordinary visual imagination of his subjects is exemplified in every one of the individual portraits: here is the Iowa tribe member, Wash-Ka-Mon-Ya, Fast Dancer, A Warrior (see main image) in earrings, necklaces, feathers, with a green forehead, red ornament and a green painted hand covering his mouth as facial embellishment.

Catlin painted the warrior chief Black Hawk when he was a prisoner of war in Missouri, holding a dead eagle, the artist’s sympathies evident. Black Hawk is a striking presence, in his fringed animal skin shirt, wearing a looped necklace and intricate double earrings and with red and green paint on his forehead. In Black Hawk’s autobiography, his question can still not be answered: “Why did the Great Spirit ever send the whites to this island to drive us from our homes and introduce among us poisonous liquors; liquors, disease and death? They should have remained in the land the Great Spirit allotted them.” Smallpox as well as guns killed them, and alcohol intolerance remains a plague to this day. (Pictured above left, La-dóo-ke-a, Buffalo Bull, a Grand Pawnee Warrior Pawnee, 1832).

Catlin painted the warrior chief Black Hawk when he was a prisoner of war in Missouri, holding a dead eagle, the artist’s sympathies evident. Black Hawk is a striking presence, in his fringed animal skin shirt, wearing a looped necklace and intricate double earrings and with red and green paint on his forehead. In Black Hawk’s autobiography, his question can still not be answered: “Why did the Great Spirit ever send the whites to this island to drive us from our homes and introduce among us poisonous liquors; liquors, disease and death? They should have remained in the land the Great Spirit allotted them.” Smallpox as well as guns killed them, and alcohol intolerance remains a plague to this day. (Pictured above left, La-dóo-ke-a, Buffalo Bull, a Grand Pawnee Warrior Pawnee, 1832).

The ramifications and consequences are still shocking, and Catlin’s determination to paint these people remains a prescient, far-sighted, imaginative and unusual achievement even now: he has left by far the most extensive record of an enormous cultural range of living practices and beliefs. He travelled Europe for eight years with his Indian Gallery, and remains the most exhibited American artist in the history of the Louvre, but was unable to sell his collection to the American government. Most of it was sold privately to Philadelphia industrialist Joseph Harrison, whose widow gave it to the Smithsonian in 1879. Thus through a series of serendipitous accidents this extraordinary collection publicly bears crucial witness to a continent-wide chain of indigenous cultures. Although Catlin’s work determines many an image of the native peoples of North America, these are portraits, not stereotypes. It is a mesmerising array of individuals - much to look at and even more to think about.

- George Catlin: American Indian Portraits at National Portrait Gallery until 23 June, and at Birmingham City Art Gallery from 12 July–13 October

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name