Lives in Music #2: How Music Works by David Byrne | reviews, news & interviews

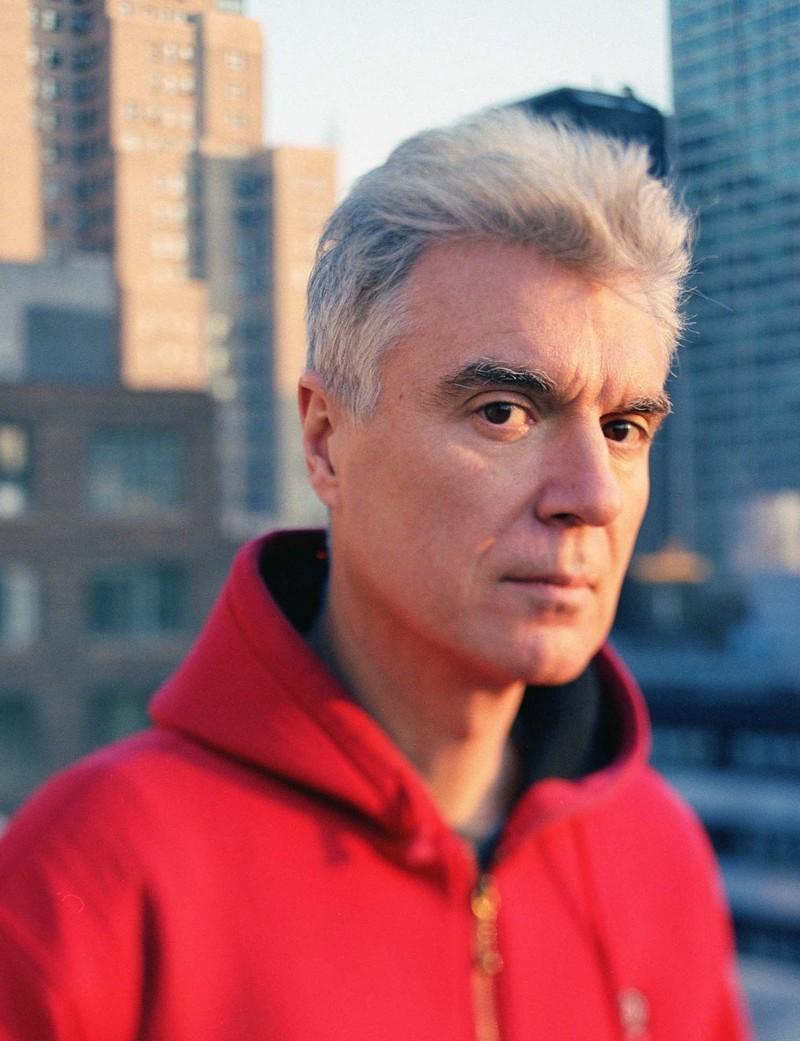

Lives in Music #2: How Music Works by David Byrne

Lives in Music #2: How Music Works by David Byrne

A pleasant jog through the history and mechanics of music but you don't feel the Byrne

Reading How Music Works feels a bit like breaking into David Byrne’s house and randomly nosing around the Word files on his computer. First there’s some stuff about whether specific types of music were subconsciously written with certain acoustic spaces in mind, then there’s a biographical bit about Byrne’s experiences as a performer.

These non-biographical sections are perfectly readable if sometimes unnecessarily pedantic; does the kind of person likely to pick up this book really need to be told that an organ is “a large wind instrument”? I suspect not. So one scans ahead, looking for the next passage in which the one-time Talking Head front man is idiosyncratically subjective, because that’s what he does best. Here’s one such example: “Making music is like constructing a machine whose function is to dredge up emotions in performer and listener alike.” Echoes of Eno there, certainly, but those two were like peas in a space-pod for a brief but exciting period in the late 1970s (see photo below). So one yearns for a more detailed account of what went on when they were the Braque and Picasso of art rock, tearing apart and then reassembling the very fabric of pop music, learning as they went along, creating the groundwork for decades of sample-based music to come.

Rather than play his cards close to his chest, Byrne doesn’t even take then out of their polythene wrapping

When Byrne does discuss My Life in the Bush of Ghosts – the pair’s most radical yet still timelessly listenable experiment in found vocals and pseudo tribal beats - his excitement is touchingly conveyed. Their discovery that any spoken-word sample (although the term “sample” didn’t then exist) seemed to adapt to its new sonic environment by appearing in tune and dramatically appropriate to its new context was ground-breaking. Plus of course it’s interesting to be reminded that this album was edited by razorblades rather software, as computers were still a long way off being a viable tool for the composer.

So why didn’t Brian Eno and Byrne work together again for three decades? A clash of egos or simply the fact they were both too busy? And why is it unlikely there’ll ever be a Talking Heads reunion? Such topics aren’t even touched upon in this book. Rather than play his cards close to his chest, Byrne doesn’t even take then out of their polythene wrapping. Instead, he moves swiftly on to yet more QI-like facts on the evolution of musical instruments and the mind-boggling metaphysical strangeness of music’s relationship to the mathematics that underlies everything in the universe. In one chapter he even channels his accountant to suggest ways a musician in the 21st century can still earn a living, complete with numerous pie charts.

So why didn’t Brian Eno and Byrne work together again for three decades? A clash of egos or simply the fact they were both too busy? And why is it unlikely there’ll ever be a Talking Heads reunion? Such topics aren’t even touched upon in this book. Rather than play his cards close to his chest, Byrne doesn’t even take then out of their polythene wrapping. Instead, he moves swiftly on to yet more QI-like facts on the evolution of musical instruments and the mind-boggling metaphysical strangeness of music’s relationship to the mathematics that underlies everything in the universe. In one chapter he even channels his accountant to suggest ways a musician in the 21st century can still earn a living, complete with numerous pie charts.

The issue is that there are other sources for much of this stuff written by people who aren’t David Byrne and therefore couldn't give us what Byrne alone could have given us. In the last couple of years alone there’s been Greg Milner’s Perfect Sound Forever which is an excellent and thorough look at the history of recorded sound, and Oliver Sacks's Musicophilia if you're looking for some kind of insight into how pleasing vibrations in the air can make us feel happy, sad, sexy or aggressive. But can Byrne be criticised for not writing the book he didn’t set out to write in the first place? In the Acknowledgements he declares that How Music Works was meant to be part biography and part “a series of think pieces.” Which would have been fine, of course, if the reader had been informed of this at the outset and therefore could have lowered their expectations a little.

However, Talking Heads heads will be delighted to learn that those strange animal noises in the background of the song "Drugs" were made by koala bears (recorded by Byrne when on holiday in Australia), not some ostensibly fiercer creature. And it’s fascinating to find out that vibrato was originally used by out-of-tune singers and instrumentalists to disguise pitch issues by effectively blurring the end of the note; because today if a violinist doesn’t create an emotive wobble at the end of a melodic phrase we’d think them amateurish. So in conclusion, this is a pleasant enough jog through the history and mechanics of music, but I just didn't feel the Byrne as much as I’d like to have done.

Brian Eno & David Byrne’s "Mea Culpa"

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

theartsdesk on Vinyl 93: Led Zeppelin, Blawan, Sylvester, Zaho de Sagazan, Sabres of Paradise, Hot Chip and more

The most extensive, wide-ranging record reviews in the galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 93: Led Zeppelin, Blawan, Sylvester, Zaho de Sagazan, Sabres of Paradise, Hot Chip and more

The most extensive, wide-ranging record reviews in the galaxy

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Add comment