William Burroughs: All Out Of Time and Into Space, October Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

William Burroughs: All Out Of Time and Into Space, October Gallery

William Burroughs: All Out Of Time and Into Space, October Gallery

Burroughs’ method for making art was to use chance to see what was happening on the other side, the far side

October Gallery first mounted a show of William Burroughs’ paintings in 1988, soon after the writer had published The Western Lands, the last novel in his final trilogy. More books would come – on lemurs, pirates, Madagascar, cats, dreams – but no further fiction.

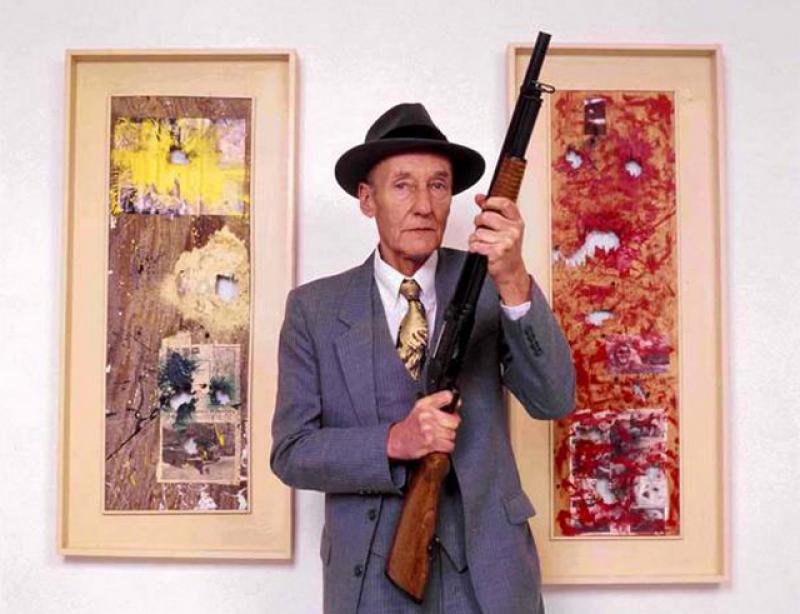

Some of them are here, and they dominate the show with visceral impact. His method was simple: blast away at plywood panelling and then step forward, not back, to examine the damage and exploded paintwork, often under a magnifying glass, for what he called his "allies" – the intimations and hypnagogic-like creatures emerging from the chance operations of gunshots engaging paint and wood at high velocity. Like his cut-up trilogy of novels from the 1960s - The Soft Machine, Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded - Burroughs’ method for making art was to use chance to see what was happening on the other side, the far side – the occult, self-creating, magickal realm of mind, as opposed to conscious intention.

What you get is that whole freight of 20th-century Beat, avant-garde and pop cultural exploration

There’s been several shows of Burroughs’ visual art in recent years – at Riflemakers in Soho; the Royal Academy’s Burroughs Alive in 2009; Maggs Books’ show of his photographs from London in the Sixties and Seventies. The October Gallery also hosted a major Gysin show a few years ago, featuring a working Dreamachine – Gysin’s flicker device employing a turntable, a light bulb, and an aluminium tube cut with geometric patterns. More recently, a new generation of dreamachines was launched at Modern Panic at Hackney’s Apiary Studios at the end of November, and here at the Burroughs show, you see his debt to and continuation of Gysin’s methods as soon as you walk in the door. (Pictured below right: Portrait of the Artist as a Psychotic Junkie, 1959)

Gysin’s works – canny investors take note – were quite cheap, just a few thousand pounds for a stunning calligraphic landscape, for instance. The cheapest of the Burroughs paintings here – a series of messy Rorschach tests on file dividers and not particularly interesting – begin at around £4,000, while the big shotgun pieces here weigh in at more than £20,000. But that is what you pay for a brand name, and an archetypal act, and in the case of Burroughs, what you get is that whole freight of 20th-century Beat, avant-garde and pop cultural exploration and invasion. Burroughs’ Cut-Up methods found their way into music, film and performance, and even the smartphone now cuts up one’s progress down the street – any street - with voices, images, music, maps, apps. Life is a cut-up more than ever, and Burroughs remains our chief predictive texter in a world gone Nova.

Gysin’s works – canny investors take note – were quite cheap, just a few thousand pounds for a stunning calligraphic landscape, for instance. The cheapest of the Burroughs paintings here – a series of messy Rorschach tests on file dividers and not particularly interesting – begin at around £4,000, while the big shotgun pieces here weigh in at more than £20,000. But that is what you pay for a brand name, and an archetypal act, and in the case of Burroughs, what you get is that whole freight of 20th-century Beat, avant-garde and pop cultural exploration and invasion. Burroughs’ Cut-Up methods found their way into music, film and performance, and even the smartphone now cuts up one’s progress down the street – any street - with voices, images, music, maps, apps. Life is a cut-up more than ever, and Burroughs remains our chief predictive texter in a world gone Nova.

As James Grauerholz, Burroughs' friend and facilitator for many years, writes in his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, “William was a foreseer. He foresaw our new century. He saw into the shadows of his times, and he discerned the roots, deep in those darknesses, of what and who – today – we all know are the real Nova Mob.”

And that Nova Mob, says Grauerholz, is the mega-rich, the banking rich, the gargantuan climate-changing energy-rich conglomerates, the 147 (he’s counted ‘em) shale-heavy transnational corporations that own the vast majority of all wealth on earth. “The processes set in inexorable motion by the Industrial Revolution, with its total commitment to quantity and quantitative criterion, are just beginning to reveal themselves as the death trap that they always were,” Burroughs wrote in his book of essays, The Adding Machine, and his writing was a warning and a search for ways out from the shadows of the Nova Mob.

And his art, here at the October Gallery, looks for the same ways into inner space and outer freedom. In a cabinet in one room you’ll find what the gallery calls his "talismanic art objects" - a grid-cut paint roller used by Brion Gysin; a paint-splattered toilet plunger, a stencil of an erect phallus, a cat, the alien heads that loom up in his shotgun art; a handgun; a tangle of plastic netting; gunshot-peppered target sheets. (Pictured left: Wood Spirits, 1987).

And his art, here at the October Gallery, looks for the same ways into inner space and outer freedom. In a cabinet in one room you’ll find what the gallery calls his "talismanic art objects" - a grid-cut paint roller used by Brion Gysin; a paint-splattered toilet plunger, a stencil of an erect phallus, a cat, the alien heads that loom up in his shotgun art; a handgun; a tangle of plastic netting; gunshot-peppered target sheets. (Pictured left: Wood Spirits, 1987).

On the walls, you will find crude, gunshot-peppered line drawings of Gysin, of Jack the Ripper (a recurring theme), and of self-portraits that look like automatic drawings drawn from the midst of sleep paralysis. The technique is crude, and on a technical level, much of his artwork is inferior to Gysin’s, while owing much to its pioneering example. But there is enough that stands on its own terms, and draws you in – and draws you in close – to a uniquely Burroughsian universe.

Folk Heroes is a collage of finger-painted ink against a photo of legendary Mexico City drug pusher Lola la Chata ("snub-nosed Lola"). The Exterminator Between Walls is a dark, fractured grid scored with an ectoplasm of milky whites, and a collage photo of Samuel Beckett with great hair. Orpheus, Don’t Look Back is a splurge of red marks, blots, lines and loose grids that shimmers with abstract detail and perpetual suggestion and intimation. After making these works, Burroughs would spend time behind a magnifying glass looking for his familiars. Visitors to All Out of Time and Into Space are advised to do the same.

Or, for a change of pace, go out the back door, walk across the courtyard, and climb the three flights of stairs to a projection room festooned with Moroccan carpet and cushions, where you can watch classic 1960s films Towers Open Fire, The Cut-Ups, Bill and Tony ("Where are you, Bill?" "I’m in a 1920 movie, Tony") and William Buys a Parrot – on a permanent loop. When The Cut-Ups was first shown in the mid-Sixties at a cinema on Oxford Street, the manager reported an unusually large number of items left behind by a disoriented audience – hats, coats, bags, even underwear. Visitors should take care they do not also leave vital parts of themselves behind when they go.

- William Burroughs: All Out of Time and Into Space at October Gallery until 16 February

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment