theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Roger Rees | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Roger Rees

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Roger Rees

Remembering the star of Nicholas Nickleby and much else, who has died aged 71

Roger Rees, whose death at the age of 71 was announced yesterday, never intended to act. He trained at the Slade and made extra money painting theatrical scenery. One day a director asked if he’d like to act, and he laid down his brush. The second time he applied to join the RSC, he got in. He stayed with the company for a now unimaginable 22 years and in due course became one of the great stars of British theatre in the 1980s.

He was a mercurial Hamlet, but overwhelmingly his best remembered performance was in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. The eight-and-a-half hours’ traffic of Trevor Nunn’s 1982 production for the Royal Shakespeare Company, so teeming with life and mould-breaking theatrical flair, made a star of its lead actor. He won an Olivier in London, then a Tony in New York, and went on to originate the lead roles in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing and Hapgood. Then Rees was offered a part in the US sitcom Cheers and upped sticks to California. Latterly he became familiar to West Wing wonks as the British ambassador Lord John Marbury. Like Robin Colcord, the limey tycoon he played in Cheers for two and a half years, this was an American script-writing consortium’s notion of what an advantaged Englishman might be. “I had to say: ‘How are you, old sock?’”

I’ve learnt to say that I carry my nostalgia with me

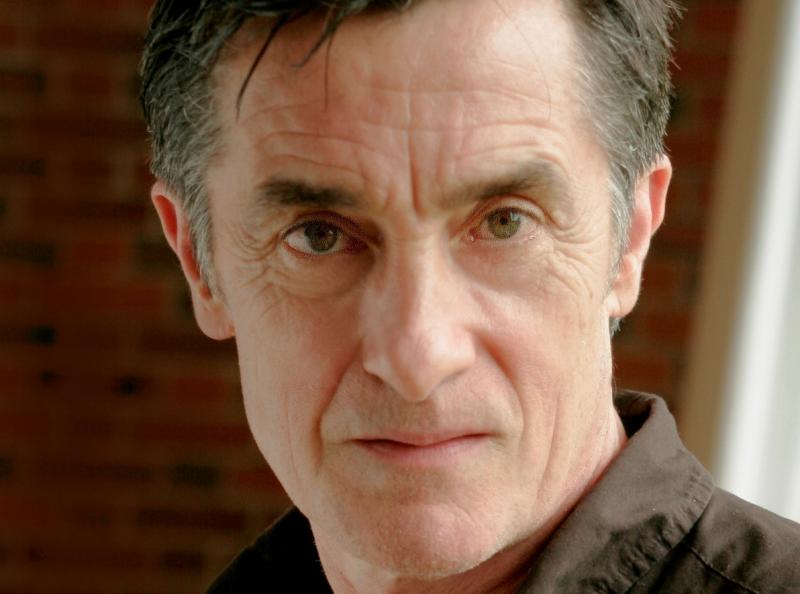

When I met Rees three years ago, time had left its wrinkled imprint on the sharp Celtic contours of his face. Whatever else he spent his dollars on, he had mercifully not bothered with Botox. But in spirit he had much more of the satchel than the bus pass about him. His sentences restlessly scurrying all over the shop, he exuded that Peter Pan quality which Nunn must have been seen when he cast a 36-year-old actor to play Dickens’ volatile teenager.

Rees seemed to have been entirely lost to the country of his birth, but in 2010 he made a prodigal return for the Theatre Royal Haymarket’s revival of Waiting for Godot opposite his old chum from the RSC, Ian McKellen. In 2012 he was back in the West End again, this time in What You Will, a show he created to allow him to share his anecdotal memories of the RSC while delivering the famous soliloquies. As well as giving London audiences a swift sense of a great actor’s skill as a Shakespearean performer, it let him indulge for 90 minutes every night in the fantasy that he never left Stratford.

Rees seemed to have been entirely lost to the country of his birth, but in 2010 he made a prodigal return for the Theatre Royal Haymarket’s revival of Waiting for Godot opposite his old chum from the RSC, Ian McKellen. In 2012 he was back in the West End again, this time in What You Will, a show he created to allow him to share his anecdotal memories of the RSC while delivering the famous soliloquies. As well as giving London audiences a swift sense of a great actor’s skill as a Shakespearean performer, it let him indulge for 90 minutes every night in the fantasy that he never left Stratford.

“I thought I could sit by the banks of the Avon," he told me, "and be in Shakespeare plays for the rest of my life, and I would be happy because one’s curiosity is never satisfied. I’ve learnt to say that I carry my nostalgia with me. I still suddenly get moments where I’m getting on a bus on a hot day in Burbank and I get a sense of a frosty morning in Warwickshire going down to the pub to have a gin and French.”

Never was there a career of two quite such distinct halves. To commemorate a fine actor, theartsdesk republishes this conversation about Shakespeare, Dickens and coming home.

JASPER REES: Where did the idea for a one-man show come from?

ROGER REES: I am an anthologist. It started when I was in the RSC working with Judi Dench and Ian McKellen. I did a show about the demise of the British called And Is There Honey Still For Tea? Then the American who runs the Folger Library theatre department said, “It should really be only about Shakespeare.” I started to think about it in my way, which is somewhat laterally. Then I remembered being told at the RSC these anecdotes about mishaps and fun things happening onstage which are nothing about anybody who is living. You add an actor from your period and say it’s about them. I know a lot of soliloquies and they’re quite interesting to do and talk about. If you had a goal it’s to endorse the humanity in the writing.

I’ve performed it for the last five and a half years. I’ve noticed that gradually more and more of my own story as a rather shy boy who was going to be a fine artist and became an old loquacious actor who discovered that you have to talk about things. I talk more and more of my journey as an actor through Shakespeare, being frightened of speeches and having the courage to do them. I talk about my father a lot who I didn't know very well and never saw me act. It’s seemingly haphazard but it resonates rather well.

How many years since you have performed Shakespeare in this country?

When I last played Hamlet and Berowne and I think that was 1984. When I did Godot it was 34 since Ian McKellen had acted together. You think, my God it’s incredible I’m still able to walk! The very first play I was ever in at the Royal Shakespeare Company where Ben Kingsley and I were spear carriers was The Taming of the Shrew. Ben and I did so well in those parts that we went on to be non-speaking huntsmen in almost every Shakespeare play.

You must have heard many times how much Nicholas Nickleby was life-changing for those who saw it.

You must have heard many times how much Nicholas Nickleby was life-changing for those who saw it.

I suddenly saw what theatre could do” or “I suddenly saw that theatre isn’t like a movie”. I have to say right back and I’ll say it to you now that it changed my life too. It’s thrilling and at first I got a little bit stupid about it. I found myself so involved in it psychologically, I found myself being a bit precious about my response. But then I realised it’s really interesting to talk about it, about how they felt and to know their names. It’s actually good because that’s the interchange you want with an audience. It’s there to be had and I think people actually celebrate and remember and mark their calendar when they saw that play. It’s a great great thing. It happened exactly the same in America as it was here. Rather like the Coronation, people go, “That was the day I saw Nicholas Nickleby.” I saw the coronation on the very first TV I’d ever seen. It was above a pub in Clapham Junction. My dad who was a policeman on the route got my mum and brother and me to sit right at the back of the room of a pub and it was a tiny nine-inch screen. We couldn’t see anything.

How long was Nicholas Nickleby in your life for?

Someone once wrote that my performance had a sheepish impetuosity which I thought was very clever. He’s a very repressed boy

It was about three and a half years altogether. The Arts Council has threatened to close the Aldwych which was the crise that encouraged Trevor to think that we needed to do something that had no royalties to pay and could use the present company. We had about 60 actors doing 13 small plays and seven big Shakespeare plays. I think he was thinking about doing a George Eliot novel or Nicholas Nickleby and Nicholas Nickleby offered more to the company. And so in that summer we started to dissect it. Each of us would take or be given [a section of the book]. It was terribly democratic to start with; eventually it became impossible to administrate and David Edgar came in to tidy up what we were doing – but those early months were spent making the play. We were doing all those other plays, so we worked on Sundays, all through the night. I remember John Woodvine composed a Victorian opera, Ben Kingsley investigated the sewage system. Because I was still a juvenile character actor I imagined that eventually I would play Mr Mantolini, a part that John McEnery played. There were lots of young kids in the company who looked just like those Phizz drawings. I didn’t feel I was like that. I’ve always been like a short three-foot high comedian in an eccentric leading man’s body. I wish I looked like I felt as an actor.

How early on did you realise he was going to cast you?

Not at all. There was a day where it was too much for Trevor, Trevor wasn’t there that day, and John Caird had to read out the list. And through this whole process people left, angrily, not only about that day. People joined us, people got married, people died. All human life was there.

Is Nicholas a blank page?

Not at all. The words that Dickens gives you are the crossword puzzle or the detective story. Someone once wrote that my performance had a sheepish impetuosity, which I thought was very clever. He’s a very repressed boy, deeply deeply formatted by his father and his responsibility, who has got a terribly violent side to him. And that’s completely interesting. He’s someone who does two things at once. That’s all you want. So he’s able to go completely out of control. He can’t control it. It’s such an early novel too, but that he’s flawed is fantastic. That counters all the things that George Orwell says about these characters. He says, “I hate all these fucking books where all the middle-class characters get the money in the end and all have children.” But then Trevor so cleverly had Nicholas pick up the next generation of people in need in that production. It had some sense of progress.

Can you describe the sensation of discovering that this play would be profoundly loved?

We all had a sense that it was wonderful and that David Edgar eventually diluting and tidying up from our assembled improvisations or writing. When Smike says to Nicholas, “You are my home,” it’s exactly what Dickens was writing though he never wrote that. So we had a sense that what we were doing was worthy but it wasn’t until the end of that first week and the audience wasn’t very populated and Bernard Levin came and just opened the door. He said, “You should really come and see this.” We hadn’t put on part two. We were rehearsing to put it on in 10 days’ time. And we were exhausted. Within that depletion we weren’t able to have clarity. So we just needed someone else to say, “Oh this is quite good actually.”

When did people start saying it had opened their eyes?

As we got part two on and as the story completed itself. You have to remember that once this play was 15 hours long. The person who thought it was too long was the carpark attendant at Stratford-upon-Avon. I remember giving Trevor a lift once and we said, “Goodnight, George.” He said, “’ow’s it going?” Trevor said, “It’s all right. It’s 15 hours long.” He said, “What about the rules?” “There’s no rules in the theatre,” Trevor said. And this guy said, “Yeah but there’s rules at the Warwickshire Transport Association. The buses stop at 12.”

Watch a clip from Nicholas Nickleby

How did it change your life?

I feel I got the part because I’ve got a lot of stamina. I’d played a lot of Shakespeare parts by then. I’d also spent 18 years carrying shields and bodies around the stage. Twenty-two years I was there. So I’d built up a lot of strength. Everyone commiserated with David Threlfall because he played this crippled person, bent over, had to have therapy every day, hand trailing on the floor, drool coming from his lips. But no one was sympathetic to me because I was 36 and I had to pretend to be a skinny young 19-year-old. And that’s much much much much harder to do.

I’m not convinced you’ve answered that. What changed? You became a star.

I’m not convinced you’ve answered that. What changed? You became a star.

No I came back and did a musical called Masquerade at the Young Vic. If I’d been looked after then of course I would have stayed in America and done movies straight away. I did six months after that do Star 80 with Bob Fosse which was an incredible experience. I should have stayed there and become a big something. But what I like to do is work a lot and so I came back and did this musical directed by Frank Dunlop at the Young Vic, the musical where Andrew Lloyd Webber met Sarah Brightman. She played a daffodil and I played a hare. I was too obedient. I’ve never really been that selfish about that sort of thing.

I was in a suit and they were all wearing like Speedos

Have you ever really grown up? I can still see the 19-year-old.

Oh good. I don’t feel I’ve ever had a proper job yet. I sort of feel I haven’t left school. I think there’s a lot to do. So a young energy seems appropriate to that. But I play lots of old farts. I’m trying not to play headmasters or lawyers too often.

What were the circumstances in which you decided to go and live in America?

I went over with Hapgood which I’d played in the West End. The Cheers people saw me one night and they asked me to come and see them. Cheers is this TV programme. You get it over here, right?

Trust me, it was big over here.

Not to me at that time. I went to this interview with them and I was in a suit and they were all wearing like Speedos and things because it was Los Angeles – I felt such a prat – and they said, “And did you enjoy Cheers?” I knew there was this dark brown programme late at night but I’d never seen but I said, “I is without doubt the thing I loved more than anything on American TV.” I don’t know if that got me the part. But that happened and I started to do that and then my mum was staying with me in Los Angeles and my brother died and she lasted for three months. It was unacceptable that he would die out of order. She spent three months yelling, “Why not me? Why not me? Why not me?”I had to take her back. The people in Cheers were fantastic. They kept giving me first-class tickets so I could get back and tidy things up. While she was ill my mum said an incredible thing. She never swore ever, although she liked a dirty story but it was always skirting around any violent language. I said, “You know I really can just come back.” I had a house next door to her. I said, “I can just come and live there and work in England. I can work anywhere.” She was very ill and had people from the council looking after her every day but she had a little dog and she could take the dog for walks. She said, “Why don't you fuck off? You make me feel ill.” Which is the best thing she ever said to me. Which meant, “I’ve had my life and I want you to have yours and I know you like America.” I came back to spend Christmas with her and she died on Christmas Eve. So the dog was the end of my dynasty. So I brought the dog back to Los Angeles and bought a house and carried on doing Cheers. But with a house and a garden for the dog. And he lasted for six years.

You've travelled a long way from Aberystwyth. How Welsh are you nowadays?

My grandmother spoke Welsh. My dad didn't. I grew up in Aberystwyth, then we moved to London when I was nine. My mum’s from Ramsgate and she’s French. They were one of the five families that came over with William the Conqueror.

How often do you go to Wales?

There is an orchard that my grandmother left me and I like to go and sit in that. Salop. It’s in England now. I think that orchard was where I was conceived.

Very Shakespearean.

My mum said she had a good time in that orchard. She told me.

Roger Rees, born in Aberystwyth on 5 May 1944, died in New York on 10 July 2015

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment