Extract: Bred of Heaven - George Borrow's Wild Wales | reviews, news & interviews

Extract: Bred of Heaven - George Borrow's Wild Wales

Extract: Bred of Heaven - George Borrow's Wild Wales

From Jasper Rees's new book on Wales and Welshness

George Borrow, embarking on the journey which would become the classic Victorian travel book Wild Wales (1862), sped towards the country by train in, he reports, a melancholy frame of mind “till looking from a window I caught sight of a long line of hills, which I guessed to be the Welsh hills, as indeed they proved, which sight causing me to remember that I was bound for Wales, the land of the bard, made me cast all gloomy thoughts aside and glow with all the Welsh enthusiasm with w

Borrow is the only notable author of a travel book about Wales who took the trouble to learn the language. Wherever he went, predominantly in North Wales and always on foot, he performed a sort of informal census, measuring levels of Welsh and English among the people he encountered. The further north and west he went, the more Welsh he found. “Dim saesneg,” passers-by and tradesmen, maids and farmhands would say when he asked them a question. No English. The further south and east, the less Welsh he heard until just beyond Newport the language petered out altogether.

Borrow was a gifted amateur philologist who had learnt Welsh as a young man in Norfolk, to which he added a knowledge of Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, Gaelic, Romany and several more mainstream languages. When Wild Wales was published in 1862, eight years after the travels it describes, reviewers noted his eagerness to parade his linguistic skills. He faithfully recorded all conversations in which it was discovered with amazement that he could speak the language. “I never heard before of an Englishman speaking Welsh,” said a man in Wrexham. “Is the gentleman Welsh?” wondered one man near Llangollen; “he seems to speak Welsh very well.” “It will be a thing to talk of for the rest of my life,” said a carpenter on the road to Bangor. One hostile Welshman, Borrow noted on the road to Llanfair in Anglesey, was “confused at hearing an Englishman speak Welsh, a language which the Welsh in general imagine no Englishman can speak, the tongue of an Englishman as they say being not long enough to pronounce Welsh”. On the way to Llanrhaeadr another woman “had no idea it was possible for any Englishman to speak Welsh half so well”.

None knew quite what to make of him. In the north they mistook him for a South Walian. In the south they assumed he was North Walian. He sometimes pretended that he could barely speak Welsh, before gradually revealing the full extent of his fluency. “I have a little broken Cumraeg, at the service of this good company,” he said on sitting down to a beer in Anglesey. “Your Welsh is different from ours,” he was soon being told by an old man, “and of course better, being the Welsh of the grammar.” And no wonder. “How were you able to master its difficulties?” asked a doctor in Snowdonia. “Chiefly by going through Owen Pugh’s version of Paradise Lost twice,” Borrow replied, “with the original by my side.”

He seems to have been racked with insecurity. Time and again, as he sought out conversations with those he met in Wales, his instinct was always to best his interlocutor. He travelled with the humility of a pilgrim paying homage to his bardic heroes - Goronwy Owen, Twm o’r Nant, Dafydd ap Gwilym - but also the zeal of a preacher spreading his own certain knowledge. Nothing delighted him more than to engage lowly shepherds and innkeepers and indoctrinate them with his enthusiasm of their culture, often in absurdly long screeds. He wandered across Wales lecturing Welshmen about their own history, the derivation of their own place names, sometimes reciting his own poetic translations. His intentions can be read honourably as a project to re-inseminate Wales with its own oral history. But for all his evident love of language and landscape, how does one respond to a man who was so careful to record every compliment paid to him? After a pleasant encounter with a slate miner and a mountain ranger one Sunday on his way down to Beddgelert, he couldn’t resist reporting what he overheard.

He seems to have been racked with insecurity. Time and again, as he sought out conversations with those he met in Wales, his instinct was always to best his interlocutor. He travelled with the humility of a pilgrim paying homage to his bardic heroes - Goronwy Owen, Twm o’r Nant, Dafydd ap Gwilym - but also the zeal of a preacher spreading his own certain knowledge. Nothing delighted him more than to engage lowly shepherds and innkeepers and indoctrinate them with his enthusiasm of their culture, often in absurdly long screeds. He wandered across Wales lecturing Welshmen about their own history, the derivation of their own place names, sometimes reciting his own poetic translations. His intentions can be read honourably as a project to re-inseminate Wales with its own oral history. But for all his evident love of language and landscape, how does one respond to a man who was so careful to record every compliment paid to him? After a pleasant encounter with a slate miner and a mountain ranger one Sunday on his way down to Beddgelert, he couldn’t resist reporting what he overheard.

“What a nice gentleman!” said the young man, when I was a few yards distant.

“I never saw a nicer gentleman,” said the old ranger.

Wild Wales is at its best when Borrow is tearing through the mountains, neither pace nor zeal dimmed by an August sun or an autumn drenching, ingesting experiences of every stripe as they come at him. One of the finest passages finds him waking up one morning in Machynlleth, where memories linger of the freedom-fighting Owain Glyndŵr, and setting off against all advice across the naked hostile hills of mid-Wales. Pumlumon (pictured above) is a passing landmark, the spectacular waterfalls of the Devil’s Bridge his eventual destination. On an twenty-mile walk of epic drama, he meets a typical cross-section of Welsh society: a modest old man who believes the Church of England “is the best religion to get to heaven by”, then two women who refuse to speak to an Englishman, four shoeless red-haired children, a sullen man with a donkey who “had the appearance of a rather dangerous vagabond” and a half-naked deaf mute working at a lead mine.

When he arrived at the inn in Ponterwyd, having traversed the barren hills, Borrow was greeted by a pompous innkeeper who affected not only to know “the ancient British language perfectly” but also to be a poet. As usual Borrow took pleasure in triumphantly besting him. In due course, having butted into the kitchen because the parlour fire was belching smoke, he explained to the host the reason for his visit: the stunning waterfalls in the river Mynach at the Devil’s Bridge a couple of miles to the south. The host greeted the news indignantly. “We have a bridge here too quite as good as the Devil’s Bridge; and as for scenery, I’ll back the scenery about this house against anything of the kind in the neighbourhood of the Devil’s Bridge. Yet everybody goes to the Devil’s Bridge and nobody comes here.”

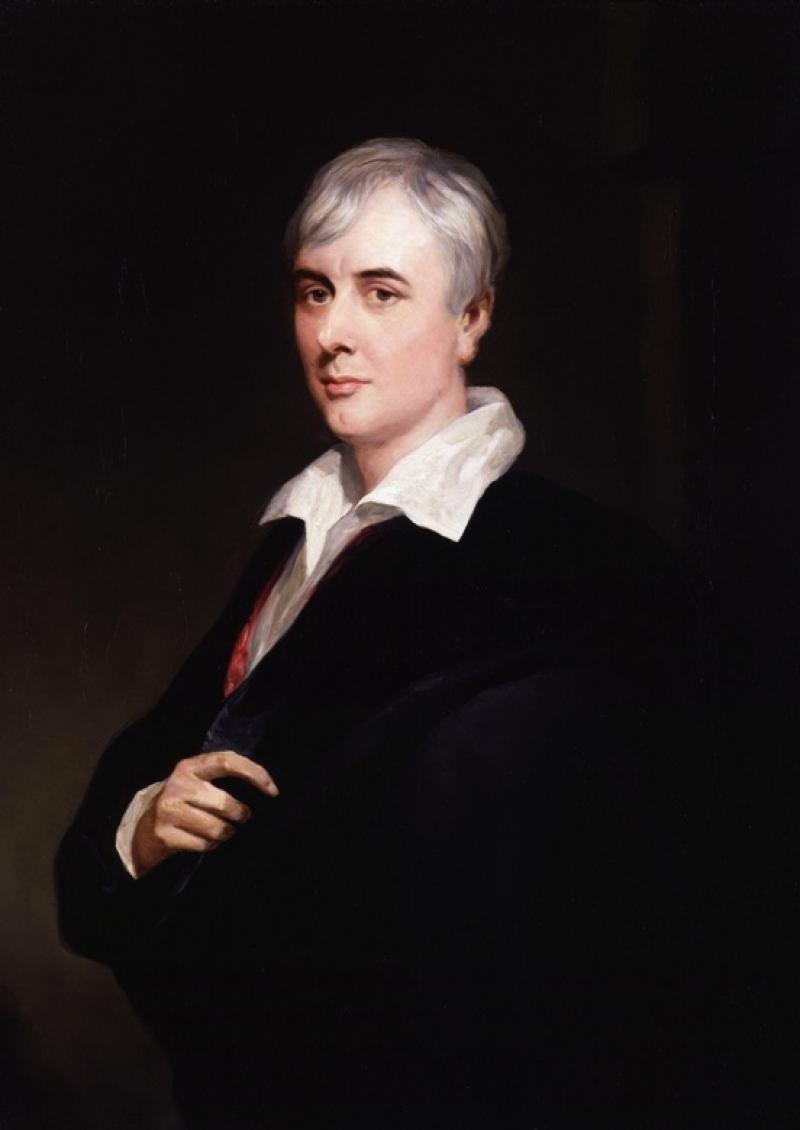

A century and a half later I sit in the same room of the same inn, now upgraded to a hotel, and read out this testy lament to the current owner. “It’s still a bit like that, to be honest.” She’s a short woman from East Sussex. They bought the place a few years earlier, her husband being a quarter Welsh. Propping up the bar is a thin retiree, all fag ash and burst capillaries, with a blotchy Black Country accent. There is a powerful sense that we are far from the beaten track. Outside, much as Borrow described it, the Rheidol still clatters noisily through a chasm at the end of the garden, as if in a roaring hurry to escape the region. The mountains of the Pumlumon range patrolling the horizon are quite as desolate and abandoned as they ever were. It feels like the ghostliest corner of Wales. Borrow was more than happy to move on to the Devil’s Bridge. But in a sense Borrow never has left. The inn has had its revenge on him: of the many places he stayed in Wales, this was a long way from his favourite but it’s nowadays known as the George Borrow Hotel (author pictured above). He would have been appalled.

A century and a half later I sit in the same room of the same inn, now upgraded to a hotel, and read out this testy lament to the current owner. “It’s still a bit like that, to be honest.” She’s a short woman from East Sussex. They bought the place a few years earlier, her husband being a quarter Welsh. Propping up the bar is a thin retiree, all fag ash and burst capillaries, with a blotchy Black Country accent. There is a powerful sense that we are far from the beaten track. Outside, much as Borrow described it, the Rheidol still clatters noisily through a chasm at the end of the garden, as if in a roaring hurry to escape the region. The mountains of the Pumlumon range patrolling the horizon are quite as desolate and abandoned as they ever were. It feels like the ghostliest corner of Wales. Borrow was more than happy to move on to the Devil’s Bridge. But in a sense Borrow never has left. The inn has had its revenge on him: of the many places he stayed in Wales, this was a long way from his favourite but it’s nowadays known as the George Borrow Hotel (author pictured above). He would have been appalled.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Album: The Hives - The Hives Forever, Forever The Hives

No power ballads, no acoustic interludes - just speedy rock’n’roll all the way

Album: The Hives - The Hives Forever, Forever The Hives

No power ballads, no acoustic interludes - just speedy rock’n’roll all the way

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Album: Benedicte Maurseth - Mirra

Haunting, intense evocation of Norway’s uplands and its wildlife

Album: Benedicte Maurseth - Mirra

Haunting, intense evocation of Norway’s uplands and its wildlife

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Comments

...

I read this book some years