theartsdesk Q&A: Playwright Martin Crimp | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Playwright Martin Crimp

theartsdesk Q&A: Playwright Martin Crimp

The innovative playwright talks about his career-long influences, his greatest hits and why he’s directing his own work

Playwright Martin Crimp is one of British theatre’s best-kept secrets. Although his neon-lit name appears in the theatre capitals of Europe, with his work a big hit at festivals all over the continent, here he is better known to students - who love his 1997 masterpiece Attempts on Her Life - than to ordinary theatregoers.

The main reason for Crimp’s comparative neglect in Britain is that his work is challenging in both form and content. (This, of course, is what attracts continental artists such as director Luc Bondy to his work.) For example, instead of being a straight play with ordinary characters and a simple plot, Attempts on Her Life comprises 17 fragmentary scenarios in which a variety of people talk about an absent character called Anne, who has several mutually exclusive identities: artist, porn star, refugee, survivalist. This absence and ambiguity deliberately removes one of mainstream theatre’s major attractions: a loveable central character. Crimp's best plays are studies in cruelty. His most recent offerings, Fewer Emergencies (2005) and The City (2008), tend to be elliptical, indirect and demand concentration. They don’t offer easy laughs or happy songs. His work is as austere as the age of austerity.

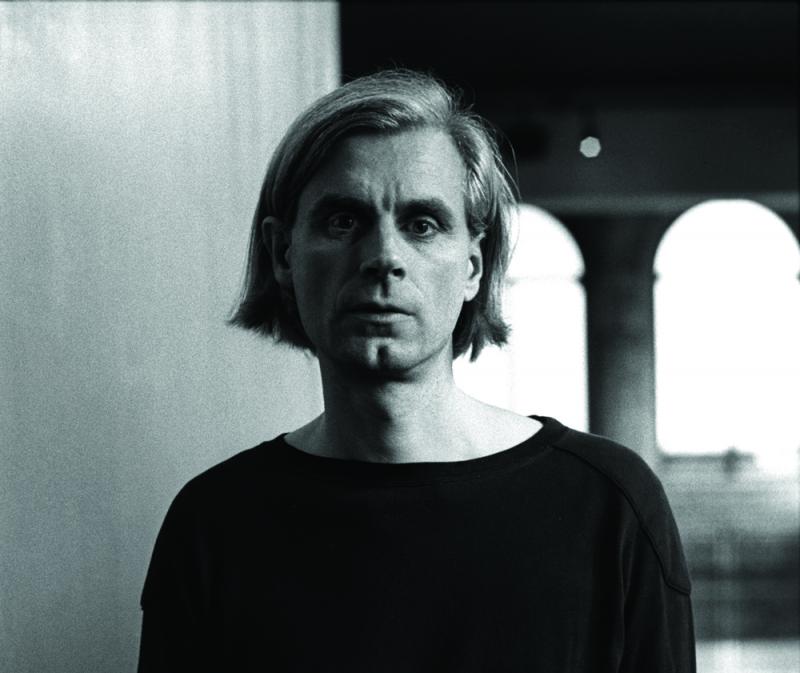

An intense, bony-faced man with a sweep of long grey hair, the 56-year-old Crimp chooses his words with the care of a perfectionist. Despite his reputation as the outstanding playwright of his generation - he was the late Sarah Kane’s favourite writer - he’s still uncomfortable in interviews. His characteristic gesture is a hand brought despairing up to the forehead. Now, as Play House, his first new play in four years, opens at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond, he talks to theartsdesk about this show, and about his career.

ALEKS SIERZ: We’re here at the Orange Tree Theatre, where your career started. Does it feel like a homecoming?

MARTIN CRIMP: While it’s true that [artistic director] Sam Walters put on six of my plays during the 1980s, you have to remember that this theatre has radically changed since that time. When my first play, Living Remains, was staged here in 1982, the theatre was in an upstairs room in the pub opposite to where it is now. You can see some posters on the walls of the theatre downstairs that advertise those early plays of mine but they really were such a long time ago. So this is more of a new adventure in discovering a new space than a homecoming.

How important were Sam Walters (pictured below) and the Orange Tree for your life as a playwright?

Oh, enormously important. Sam put on all of my work in the 1980s and that kind of commitment to a writer is incredibly valuable. Nowadays, writers that are supported by a theatre for one play or perhaps two may find themselves dropped, not given the space to develop. The enormous success of our new writing culture means that there are so many new writers that inevitably there is a large number of people competing for a small number of opportunities. And, of course, our theatre culture puts emphasis on novelty rather than commitment.

Oh, enormously important. Sam put on all of my work in the 1980s and that kind of commitment to a writer is incredibly valuable. Nowadays, writers that are supported by a theatre for one play or perhaps two may find themselves dropped, not given the space to develop. The enormous success of our new writing culture means that there are so many new writers that inevitably there is a large number of people competing for a small number of opportunities. And, of course, our theatre culture puts emphasis on novelty rather than commitment.

Were you encouraged to keep writing?

Not exactly. No one ever needed to encourage me to write then - although now they do. (Laughs.) But when I was starting, Sam was simply receptive to my work - and put it on. At the time I probably took that for granted. It’s only in retrospect I see what a great gift that was.

This show is a double bill: as well as Play House, a new work, it includes Definitely the Bahamas, a short play of yours from the 1980s. So how did this double bill come into being?

At the beginning, Sam wanted a completely new full-length play, but I told him that I wouldn’t be able to write a completely new play in a short time because I find that more and more difficult. And the play Definitely the Bahamas, which I wrote in 1986, had been revived a little while ago in Paris. So I proposed that play to him, and then I suggested that I could maybe write a new short play to go with it. That’s how Play House came about.

Sam gave me my first break as a writer and now he’s given me my first break as a director

Definitely the Bahamas was first written as a radio play...

That’s right. It won the Radio Times Drama Award and was broadcast by the BBC in 1987. Definitely the Bahamas is about 60 minutes of running time and for me that’s a bit short - although plays are getting shorter. So I decided to write another short play to go with it. Firstly, to make a longer evening, and secondly because I like a formal challenge, which in this case was: how do I create something new to go with something old? Now, Definitely the Bahamas is about the life of a couple in their late fifties/early sixties - and was written when I myself was just 30. So my formal idea was to do a kind of reverse-shot, and from my mid-fifties perspective write about a much younger pair.

And you are directing.

Yes, not only is this a completely new theatre for me, but it’s a new experience because I’m directing my own work for the first time. At the start I wasn’t in the frame as a director, and I thought I might be working with one of the young directors I’d met through doing workshops at the Royal Court, but when that didn’t work out I decided to propose myself. And Sam accepted. So what’s quite nice is that Sam gave me my first break as a writer and now he’s given me my first break as a director.

As the director, how do you see your staging of Definitely the Bahamas?

We’ve made a decision to stage the play as a live radio broadcast. The idea is that the audience is watching a live radio broadcast of the 1986 play Definitely the Bahamas taking place now in 2012 at the Orange Tree Theatre. So the stage is filled with sound equipment - like when you go to a concert that’s being broadcast. This pays homage both to the Orange Tree and to BBC Radio 3, who were the co-authors of my early career.

When I revisited the text of Definitely the Bahamas, it was very clear to me that it is taking place in a particular historical moment. Milly, for example, talks about “all these reforms” - a reference to the final repeal in 1985 of South Africa’s notorious Immorality Act. One of the things we brought into the rehearsal room is a copy of the Daily Telegraph from August 1986 which is amazingly close to the world of the play. But although the play takes place in that year, I didn’t want to recreate that era on stage using 1980s costume or music. I want the audience to imagine instead, through the play, through the language, the world of 1986 which the characters recreate for us through their performance.

Of course the interesting thing about looking at a play as a director rather than as a writer is that I notice certain passages which as a writer I may be attached to, but that as a director I may quietly cut. Also, I noticed that I had been quite heavy on the pause button in those days. That’s something else to be quietly reconsidered. (Laughs.)

There wasn’t a decision involved because writing for me was a given

Directing the text today it is quite clear to me, in a way that it really wasn’t when I wrote the play, that I was in some way thinking about my parents. Obviously, Frank and Milly are not literally like my parents, but their behaviour alludes in some ways to them - and perhaps to the behaviour of all couples of a certain age, don’t you think? (Laughs.) And I think that the task I was setting myself was to capture something about the way that people really speak. And this is the first play of mine that I felt I had done that in a way that was wholly my own.

In the new play, Play House, the young couple are Simon and Katrina. How did the play come about?

As I said, I enjoy the idea of having one element in place and then using that to make a new work. I wanted to write about two young people, and also I wanted to do something I’d never done before, which was to write some very short and rapid scenes. It’s the first time I’ve done this and it’s very demanding, but fun.

Definitely the Bahamas has a circular structure, starting off in silence and returning to silence, and Play House alludes to that circularity because the first scene and the last scene are both declarations of love. But Play House is more open-ended - perhaps appropriately for a young couple who have none of the certainties available to Frank and Milly’s generation. What I’m trying - am I? - to explore in Play House is the fragility and above all volatility of a relationship. And the extent to which, in the world now, individuals are prepared to accommodate to each other in the name of love.

It is unsurprising that I had no idea about how to approach theatres

An image I used to introduce the plays to the actors was that of magnets. In Definitely the Bahamas Milly and Frank are north and south poles - you bring them together - and whatever happens - they stay glued together. The Play House couple are more like two identical poles - the closer they get, the more they vibrate and resist. Will they repel each other in the end? Or finally flip and stick?

Now let’s go back to the beginning. When you left Cambridge University, you obviously decided to become a writer. Could you say a few words about how you first approached the Orange Tree?

First let’s just clear up this idea of "deciding to become". There wasn’t a decision involved because writing for me was a given. Even the word "writer" seems contestable to me for the reason that it implies a profession or career or structure or something equally worldly, and that way of looking at writing as if it was a career option like whatever - investment banking - would’ve been anathema to me at that time, and still is to a certain extent. It is therefore unsurprising that I had no idea about how to approach theatres. I had no idea about what went on; I didn’t know what literary managers were. So I sent unsolicited manuscripts of my plays to several theatres. One of the theatres was the Orange Tree, which by chance was close to where I lived. Then, since I lived on the doorstep, I was called in.

What were your influences?

(Pause.) To me, looking back, it’s obvious that I was heavily influenced by Beckett. Of course, that’s a really dangerous influence, but in some ways not a bad one. Better than no influence at all. (Pause.) At the same time, I think that something more personal to me was already present - I was going to call it satire, but maybe that’s not the right word. Jonathan Swift is, of course, another Irish writer I’ve always admired and continue to read. As an adolescent, I was also a big fan of Ionesco, and I must have put on all sorts of weird plays by him at school: The Lesson, The New Tenant, and a play about the character Macbett. But I was completely unaware of the new wave of -

Kitchen-sink?

No, not kitchen-sink. Bond-type plays. Angry plays. Political plays. Which I discovered much later. So I was coming from a place which seems to me now quite strange and isolated. At that time, living in Yorkshire, I read Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute, books which I found in the York Book and Record Exchange. They didn’t always make sense to me; but they left a subliminal mark. As far as British drama was concerned there was definitely a 10-year time gap between me and everybody else.

From the beginning, with all those early and unpublished plays such as Four Attempted Acts (pictured below) and A Variety of Death-Defying Acts, there’s an interest in cruelty and control. How conscious were you of this?

I don’t think I was. Particularly. The cruelty is instinctive - if you like. (Laughs.) For me, dialogue is inherently cruel. There’s something inherently cruel about people talking to each other. And I don’t know what that is. My parents’ constant arguments as a child possibly have something to do with it. While we were recording one of my first wacky or - if you prefer - autistic radio plays in the 1980s, I met the actor Alec McCowen, and he said to me: "Martin, someone you ought to read, I think you’d really like, is David Mamet." So I thought, "Okay, I’ll read some Mamet." I did so, Glengarry Glen Ross, and of course that was the kick. Suddenly I found this different, high-speed way of writing which immediately dragged me away from these absurdist antecedents - if you like - into the real world. If I was writing a thesis about my work - my worst nightmare, by the way - I would say that in Dealing with Clair [1988] the old style meets the new style, and the old style is typified by James (played by Tom Courtney and pictured below), who is the slightly baroque, emotionally blank character inhabiting an abstract world, and he meets the new characters I’ve just discovered, the suburban dwellers whose dialogue has got a completely different fuel in it. You could say I let the banal into my work. And the banal is enormously energising.

I don’t think I was. Particularly. The cruelty is instinctive - if you like. (Laughs.) For me, dialogue is inherently cruel. There’s something inherently cruel about people talking to each other. And I don’t know what that is. My parents’ constant arguments as a child possibly have something to do with it. While we were recording one of my first wacky or - if you prefer - autistic radio plays in the 1980s, I met the actor Alec McCowen, and he said to me: "Martin, someone you ought to read, I think you’d really like, is David Mamet." So I thought, "Okay, I’ll read some Mamet." I did so, Glengarry Glen Ross, and of course that was the kick. Suddenly I found this different, high-speed way of writing which immediately dragged me away from these absurdist antecedents - if you like - into the real world. If I was writing a thesis about my work - my worst nightmare, by the way - I would say that in Dealing with Clair [1988] the old style meets the new style, and the old style is typified by James (played by Tom Courtney and pictured below), who is the slightly baroque, emotionally blank character inhabiting an abstract world, and he meets the new characters I’ve just discovered, the suburban dwellers whose dialogue has got a completely different fuel in it. You could say I let the banal into my work. And the banal is enormously energising.

Ever since you, as a teenager, saw Beckett’s Not I at the Royal Court, that theatre has been a magnet. Was the first time your work was shown there a reading of Getting Attention?

Yes, it was. It’s quite hard to talk about this play, and quite hard to watch it sometimes. (Pause.) It was an uncommissioned play and, at the time I wrote it, there were a number of influences. One was all the media reporting about child abuse. The second thing, which got up my nose, was that many well-known British novelists of the 1980s were becoming fathers, and, in response to fatherhood, they were becoming increasingly sentimental. I remember reading an interview with one of them, which talked about his wonderful study overlooking his lovely garden, and how he looked around "with concern", when he heard his child, which was being looked after by its nanny, not, you will note, by him. My experience of having children was different. It was not sentimental. It was beautiful, but hard at the same time. When I wrote Getting Attention, I wanted to confront physical - and I mean physical rather than the more fashionable sexual abuse - and, at the same time, to explore satirically some of the discourse that surrounds it. And, unconsciously perhaps, in the relationship between [the parents] Nick and Carol, there was a desire to write a hot play about relationships, a sexual relationship between two people, and about a child that gets caught between them. The child is the victim - if you like - of that.

Now, I know that your 1993 play, The Treatment, came out of a particularly unhappy experience with film; what was that all about?

Now, I know that your 1993 play, The Treatment, came out of a particularly unhappy experience with film; what was that all about?

I have two memories which can be merged into one. At the start of the 1990s, I was approached to write short films. And the scene was just like that scene in the opening of The Treatment:: one person is being asked questions by another and there’s a third person who says nothing, just watches. After I wrote the film scripts I would go to a meeting with the person who had commissioned them, and there would be another person in the room. Who were they? It was never quite clear. I was never introduced to them. It was nothing like my experience of writing for the theatre. It was a different kind of conversation. None of this work ever came to anything. And I realised I was being duped. These short films turned out to be calling cards for ambitious young directors who just wanted material they could shoot. I found the whole experience very humiliating. Then, when they were shooting the second film, I was kindly invited to see the shoot. It was taking place in Manchester. I turned up there and I couldn’t find it. I had a phone number, but no one answered. This was a quintessential Martin situation: I get off a train and I’m looking for my film in a big city. And I’ve no idea where it is. I never found them. And they never found me.

Were you stuck after The Treatment, which was a success on the Roayl Court's main stage, because you didn’t want to repeat the same formula? Were you conscious of that?

Yes, really conscious. Although I wouldn’t call it a formula. (Pause.) The fact is we don’t have any trustworthy received forms left in the arts, so every time you have to find a way of starting from scratch.

So you came up with The Misanthrope (Keira Knightley pictured below in the 2009 West End revival), a radical adaptation of a classic.

Yes, that was fun, wasn’t it? It’s funny because a play that is so full of energy came out of a period when I was feeling very miserable about writing because although The Treatment meant that people took me seriously, I found myself unable to write the next play. So anyway this play was a great way of sounding off through the persona of Alceste and at the same time having enormous fun with language. At first, I was quite nervous about writing verse, and looked at Caryl [Churchill]’s Serious Money, which reminded me that you could have free metre and still have rhyme. The problem you see with using regular rhyming couplets in English is that it comes out sounding like Alexander Pope.

Yes, that was fun, wasn’t it? It’s funny because a play that is so full of energy came out of a period when I was feeling very miserable about writing because although The Treatment meant that people took me seriously, I found myself unable to write the next play. So anyway this play was a great way of sounding off through the persona of Alceste and at the same time having enormous fun with language. At first, I was quite nervous about writing verse, and looked at Caryl [Churchill]’s Serious Money, which reminded me that you could have free metre and still have rhyme. The problem you see with using regular rhyming couplets in English is that it comes out sounding like Alexander Pope.

When The Misanthrope was revived in the West End in 2009, did you think that some parts of it had aged badly?

I knew that there were two passages which were vulnerable. And I don’t feel that they were vulnerable because of the language. Time will show to what extent the language is vulnerable, because 15 years is not very long. The passages that were vulnerable were deliberate references to contemporary politics, they were detachable chunks of about 20 lines. There is one which I always change: it originally referred to John Major’s Back to Basics campaign. And for the production for the Comedy Theatre I changed this to a little passage about David Cameron’s associations with the ultra-right in Europe. And so I always knew that the passage was vulnerable. And there are some other things. For example, there is a scene in which the character in my play called Jennifer, who is based on Celimène in the original play, slags off a whole variety of people that she knows. And over the years I have gradually adjusted this with the hope of aiming at more universality. I think there were sometimes things which were perhaps private to me, which I hadn’t seen at the time. And I have just gradually changed those, which would not really be perceptible. So that was evolution, the accruing of things over time, the survival of the elements of the play which are the most well-adapted to the world that we are living in. But really I would say that that is one percent of the text.

Let’s go back to this idea of being blocked...

Did I say that? I sometimes think that "blocked" is one of those words, like "draft", that gives writing a professional vocabulary that is in fact alien to writing itself as I see it. But it’s true that part of learning how to be a writer is that there are gaps. Unless you’re lucky enough to be a genius. There are no rules for creativity. Writing is bound up with your identity so it’s not so much that you can’t write that is frustrating, but it is the sense of disappearing when you can’t write that’s frustrating. It’s like being absent, which is something I write about - I mean, where is Anne?

That’s a neat segue. Can you tell me how Attempts on Her Life (pictured left) originated?

That’s a neat segue. Can you tell me how Attempts on Her Life (pictured left) originated?

In the gap between The Treatment and Attempts on Her Life, I reached a point of frustration with - what you might call - the normal way of writing. I was completely bored with doing "he said" and "she said" dialogues. I was frustrated with psychological drama, and bored with so-called cutting-edge theatre. Writing is no good unless there’s pleasure in it. And for a while after The Treatment I had been getting pleasure from writing little short stories in dialogue form. I felt a real urge to write in this way. And that’s how Attempts came about. I kept writing pieces like this, and then I’d look at them and say, "Sorry, Martin, this isn’t a play." Then, in the end, I thought, "Of course it is." I was pleased with the writing - it felt entirely like me, Martin-like - and it worked.

Yes, I agree. But did any other plays influence you at the time?

I remember talking to a German critic in Amsterdam, at the premiere of Attempts on Her Life there, and he asked me this irritating question about which authors have influenced me, and I said, "Well, I read a lot of James Joyce at university, but I don’t see that that has anything to do with my work now." And the guy said to me, "Ah yes, I can see what it has to do with your work: it’s the fact that when you construct a play you use motifs as a way of linking things", and I saw that he was absolutely right. So although I am no longer interested in those Joycean formalistic experiments, something from them has percolated into my work. And it’s much easier for other people to see these things than it is for me.

But was there a point when you realised that the form and content was becoming one?

Oh yes. The moment that Anne or Anny became a car. It’s one of those moments when you sit there, smiling to yourself and you realise that although you have invented this structure which appears at first glance limiting, it is actually limitless. It can be opened out in any direction. If Anny can be a car, she can be anything. And I’m free. (Laughs.) And, Tim [Albery, the director] encouraged that freedom. I always felt confident about what he was doing, and he encouraged me, in our discussions before I made a final text for rehearsal, to go as far as I wanted. He was also very professional about what he was delivering to the audience. That press night was the first opening night that I’d enjoyed for a long time.

Your version of Botho Strauss’s Big and Small (starring Cate Blanchett, pictured left) is another of your many translations and adaptations. Do these plays help with developing your writing?

Your version of Botho Strauss’s Big and Small (starring Cate Blanchett, pictured left) is another of your many translations and adaptations. Do these plays help with developing your writing?

I don’t think translating itself is particularly useful language-wise. I liken it to a kind of - maybe I do this all the time - to a sort of workout in which you flex muscles you don’t normally use; or you could liken it also to being purged - it’s a bit like being flushed out linguistically. And I’m not sure how useful that is. Reacting with a text - like one by Sophocles or Chekhov or Strauss - is quite different because that’s challenging, because it pushes you into areas which you might have considered taboo in your own work due to the fact that, of course, you build habits when you work, and part of wanting to develop as any kind of artist is to break old habits, break old patterns of working.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Add comment