Close Up on Hunter S Thompson | reviews, news & interviews

Close Up on Hunter S Thompson

Close Up on Hunter S Thompson

Rise and fall of the gonzo guru

Hunter S Thompson always had one beady, sun-bespectacled eye on posterity. At 21, living in poverty in a remote cabin in the Catskills and toiling away at an autobiographical first novel, Prince Jellyfish (still unpublished), he would immodestly compare his own progress to that of F Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, two other writers who came late to public recognition.

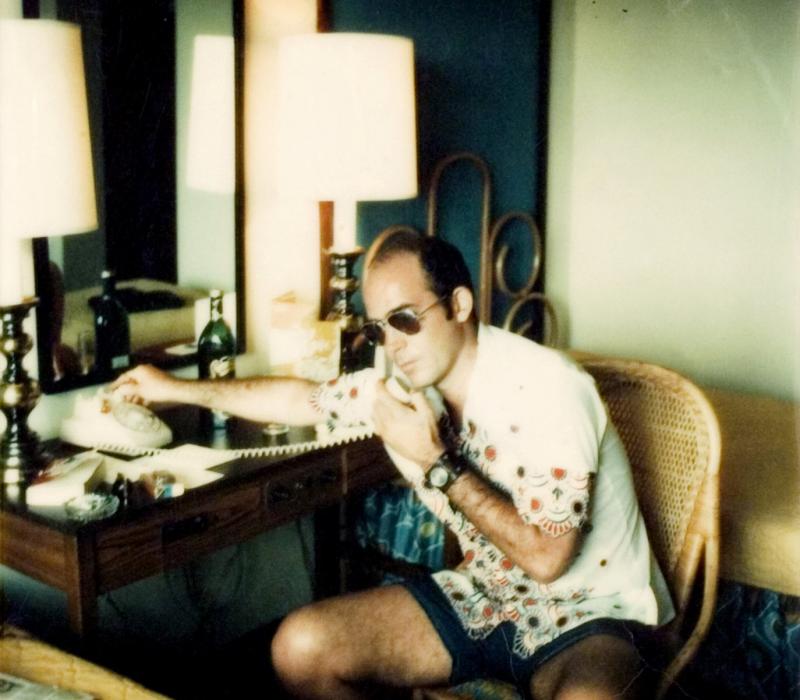

He kept files of self-portraits, which he took by setting the timer on his camera, and was even cataloguing photographs of the many empty rooms in which he had ever lived. An ardent letter-writer, he made carbon copies of all his correspondence. "I was anal-retentive in my desire to save everything," he said later. By the time the first of these letters were published, in 1997, there were 20,000 of them to choose from. Two volumes have appeared to date; a third is imminent.

Nearly half a century later, late one February afternoon in 2005, Thompson put his freshly polished .45 pistol in his mouth and pulled the trigger. He could have chosen few more effective finishing touches to his own legend. He was, moreover, providential enough to leave behind him a mountain of unholy relics to keep the flame alive.

Thompson's over-stuffed bibliography has been swelled by a wave of recent books. Gonzo by Jann Wenner, his editor at Rolling Stone magazine, was followed last year by Anita Thompson's The Gonzo Way, William McKeen's Outlaw Journalist, Beef Torrey's Conversations With Hunter S Thompson and Michael Cleverly's The Kitchen Readings: Untold Stories Of Hunter S Thompson (as if there were any untold stories left). Two more memoirs, Hunter S. Thompson: An Insider's View Of Deranged, Depraved, Drugged-Out Brilliance, by Jay Cowan, and Ancient Gonzo Wisdom, by Anti Thompson, were published last month. And a new anthology of Thompson's magazine work, The Gonzo Tapes, a five-CD set of his musings (or rantings), was released in October.

The filmography is rather ample too. Two cult actors have played him: Bill Murray (in Where The Buffalo Roam) and Johnny Depp (in Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas). There are numerous documentaries, the latest of which, Alex Gibney's Gonzo, is released today (13 April) on DVD.

And the long-mooted film of The Rum Diary, the thinly fictionalised novel which Thompson wrote while working in Puerto Rico in 1960, has just started shooting there. It stars Depp, Thompson's virtual alter ego (the actor lived in his basement while preparing Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, narrated Gibney's film and wrote the preface to Wenner's book; he even picked up the bill for Thompson's flamboyant $2.5m funeral).

The cast also includes Michael Rispoli, Richard Jenkins, Aaron Eckhart and Giovanni Ribisi; the director, Bruce Robinson, is best known for Withnail And I, whose sardonic, permanently intoxicated protagonist is Hunter's limey soulmate.

All of which raises a fair few questions. Namely, could this market for Gonziana perhaps be getting over-saturated ? And, come to that, does the good doctor deserve it ? Famously, Thompson urged his followers to "buy the ticket, take the ride." But it might be time to leap off the bandwagon.

There have always been dissenting voices. William Buckley, in his obituary of Thompson for the National Review, dismissed him as a flashy, shallow exhibitionist: "Hunter Thompson elicited the same kind of admiration one would feel for a streaker at Queen Victoria's funeral," he wrote. Reviewing Gibney's film in the Los Angeles Times, Kenneth Turan cautioned scepticism towards our culture's fascination with the kind of loose canon, the self-indulgence and the recklessness, which Thompson personified.

Perhaps his most deadly legacy has been the inexorable rise of the opinionated - but not necessarily intelligent or well-informed - columnist. Or, worse, the rambling, free-form, thoroughly unreadable, and unread, Internet blogger, none of whom commands the unrivalled platform which Thompson, back in the Sixties, enjoyed at Rolling Stone.

"Too many people have tried to imitate him," concedes McKeen, whose journalism course at the University of Florida is thronged with freshman students clutching well-thumbed copies of Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas. "But I don't think he should be blamed for it. I don't know that he intended to create a league of imposters - although that has happened."

Both he and Gibney have been accused of adopting a fan's-eye-view of Thompson, a charge which each man vehemently denies. "There's a lot of things about Hunter that are negative," McKeen insists. "For all his abilities, he was not always kind to his friends and he was abusive in a lot of his relationships with women. I see him as a genius writer but an amateur human being, full of flaws and contradictions. But that's what makes him interesting."

Gibney's film devotes some time to one of Thompson's most inglorious hours, when he was sent to Zaire in 1974 to cover the "Rumble in the Jungle" between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. The match was postponed and Thompson spent six weeks getting wasted. On the night when the bout finally happened, his $200 seat was empty. He was wallowing, stoned, in the hotel swimming pool.

In the Eighties, plagued increasingly by ill health as his lifestyle took its toll, Thompson retreated to what he called his "fortified compound", Owl Farm, in Colorado. "Hunter's heyday was when he was doing good hard reporting at the same time as finding an interesting way to insert himself into the story," Gibney says. "But he ended up wasting his rather considerable talents, instead of refining them. He became a bloviator: someone who would spout gaudy opinions and mindlessly prattle on. As time went on, he saw the world as a reflection of himself. He didn't look out as much as he looked in the mirror. And he committed suicide in a way that was not heroic but rather sad and narcissistic."

Like Gibney, McKeen sees Thompson as trapped in a myth of his own making. "He was often his own worst enemy, creating and then watering and manuring this vivid persona that threatened to suffocate his achievements," he argues. And it is, he adds, scarcely a positive sign that Thompson is the favourite author of many people who admit to never reading books.

McKeen quotes a damning assessment by Sandra, Thompson's first wife, for whom the writer's decline in later years was linked to a deep self-loathing. "He was a tortured, tragic figure," she said. "He was horrified by what he had become, and ashamed... He never became that great American writer he had wanted to be. Nowhere close. And he knew it."

Yet in McKeen's view, Thompson's handful of great successes - the 1966 book on the Hell's Angels motorcycle gangs, Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas, his coverage of the 1972 Presidential campaign and, it is increasingly emerging, his letters - are enough to insure his lasting literary reputation. Hunter's undoubted egotism was always tempered by a healthy self-deprecation. "He portrayed himself as this burned-out loser, and that was charming. He was always the butt of his own jokes," McKeen says.

"He will be remembered as the guy who recorded a personal narrative history, primarily of America, from 1950 to 2005. He was a great patriot and deeply passionate about politics and our society, although he's so funny that it masks his sometimes serious message. I believe his work will be looked back upon in the way we now look back on Mark Twain's work from the nineteenth century. He will not be a footnote or one of those flashes in the pan from 1960s psychedelia."

Gibney was working on Gonzo at the same time as Taxi To the Dark Side, his sombre, Oscar-winning documentary about Abu Ghraib, and he sees these two films, seemingly so different, as in fact odd companion pieces. "America is a country of great extremes: on the one hand, a tremendous idealism and hope for the future, and on the other hand this xenophobia and brooding vitriolic resentment - even though it's a nation of immigrants - and a refusal to engage in fair-minded discourse and instead to scream slogans and threats. It's everything that comes out of what Hunter called fear and loathing. He saw some fundamental truths about the American character and this strange country which has the power to annihilate the earth. Those observations remain as true today as they did then."

"I didn't want to go and interview a bunch of celebrities: 'Hey, what drugs did you do ? What party do you remember?'" Gibney concludes. We knew about the wild and crazy guy; that was pretty evident. We saw him every day in Gary Trudeau's cartoon, Doonesbury [which featured a thinly disguised Hunter character, pictured right]. What had been forgotten was how good the work was. No-one would give a shit about his antics otherwise."

- Documentary: Alex Gibney's Gonzo is released on 13 April 2009 on DVD

- See also The Gonzo Tapes, a five-CD set of his musings

- Selected books:

Gonzo by Jann Wenne

The Gonzo Way by Anita Thompson Outlaw Journalist by William McKeen

Conversations With Hunter S Thompson by Beef Torrey

The Kitchen Readings: Untold Stories Of Hunter S Thompson by Michael Cleverly

Hunter S. Thompson: An Insider's View Of Deranged, Depraved, Drugged-Out Brilliance, by Jay Cowan

Ancient Gonzo Wisdom, by Anti Thompson - Films:

- Where The Buffalo Roam

Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas - A version of this article appeared in The Scotsman (4 December 2008)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Anemone review - searching for Daniel Day-Lewis

The actor resurfaces in a moody, assured film about a man lost in a wood

Anemone review - searching for Daniel Day-Lewis

The actor resurfaces in a moody, assured film about a man lost in a wood

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Relay review - the method man

Riz Ahmed and Lily James soulfully connect in a sly, lean corporate whistleblowing thriller

Relay review - the method man

Riz Ahmed and Lily James soulfully connect in a sly, lean corporate whistleblowing thriller

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Add comment