Twelfth Night, National Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Twelfth Night, National Theatre

Twelfth Night, National Theatre

The party's over in Peter Hall's production laced with intimations of mortality

Set at a pivotal point in Shakespeare's canon, Twelfth Night is a glass-half-full kind of play. Is it a joyous, clear-eyed, compassionate comedy of human foibles by a writer reaching maturity, a wild and crazy ride through a season of carnival misrule and role reversal? Or, on the other hand, an ominous harbinger of the troubling, darkening work still to come?

Yet the production got off to a ropey start. Duke Orsino, unprepossessingly played by the New Zealand actor Marton Csokas in a wig that looked like an overgrown mullet, barked his way through the great opening speech - "If music be the food of love..." - as if already suffering from acute dyspepsia. It was followed by Viola's equally awkward and static post-shipwreck scene (it didn't help that one of the supporting actors dried up last night).

You can almost hear the audience heave a sigh of relief as Twelfth Night's trio of drinking buddies lurch on for their first session. Finty Williams's Maria, Simon Callow's alarmingly rubicund Toby Belch and a funny, gawky Andrew Aguecheek, played by Charles Edwards as a silly ass a few pats short of a buttery bar, briefly lift the spirits - until, that is, Feste skulks in for one of his depressing songs and they all fall back into a despondent silence.

In his 1960 essay on the play, Hall had already homed in on the jester as the play's most important character. And he doesn't seem to have changed his opinion much on this particular count in the intervening half-century. Dressed all in muddy, funereal black, a green and purple cap and bells and a few coloured buttons his only, half-hearted attempt at motley, David Ryall's creation is a scrofulous, sardonic individual, the spectre at the feast, more festering than festive.

Toby Belch sported, incidentally, the same green and purple colours, suggesting, perhaps, his character's bleakness beneath the bluff pink exterior. And the "mad" scene of Simon Paisley Day's neurotic, gangling Malvolio, crumpled in a cage like a wounded stork, was genuinely disturbing.

Toby Belch sported, incidentally, the same green and purple colours, suggesting, perhaps, his character's bleakness beneath the bluff pink exterior. And the "mad" scene of Simon Paisley Day's neurotic, gangling Malvolio, crumpled in a cage like a wounded stork, was genuinely disturbing.

You'd have thought Viola was the main role. She's played, of course, by Hall's daughter, Rebecca, with her singular brand of watchful, intelligent, slightly diffident reserve as often seen onstage as well as in films such as Starter for Ten, Frost/Nixon, Vicky Cristina Barcelona and Please Give.

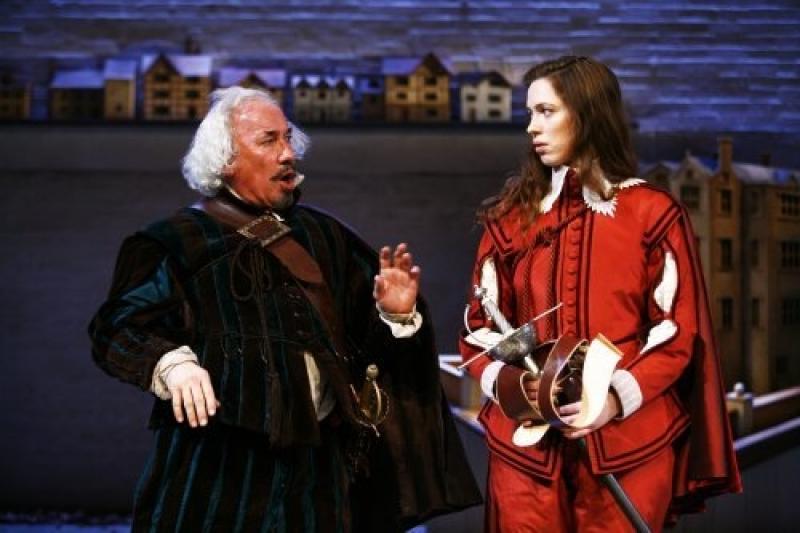

It's well suited to a character who through most of the action is standing aside, observing and dissembling, though Hall (pictured above right with Amanda Drew as Olivia) also holds her own in the physical comedy of the duel with Aguecheek. But the actress is less successful at putting over Viola's sense of mischief - though perhaps she'll grow in confidence as the run continues. And the erotic sparring with Orsino has no sexual spark at all.

The production in the Cottesloe is simply and elegantly staged with a golden autumnal set and lovely music (by Mick Sands). It all has a valedictory feel, rather than a celebratory one. At the end, as Feste treats us to one last melancholy song, a canopy of dead leaves descends upon him slowly like a shroud.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Comments

...