The Printed Image in China, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

The Printed Image in China, British Museum

The Printed Image in China, British Museum

An exhibition exploring the history of printmaking in the country of its birth

The British Museum’s current exhibition of 15th-century works on paper, Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings, explores the increasing importance of the preparatory sketch in the development of western art. Central to that development was the availability of cheaply produced paper.

The British Museum’s current exhibition of 15th-century works on paper, Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings, explores the increasing importance of the preparatory sketch in the development of western art. Central to that development was the availability of cheaply produced paper. But as we discover in the British Museum’s free exhibition of the evolution of Chinese printmaking, The Printed Image in China, paper was being successfully manufactured in China by the third century AD. This innovation, along with the invention of the compass, gunpowder and printmaking, is among what’s commonly known as China’s Four Great Inventions.

The process of printmaking is believed to have been invented in China in around 700 AD and this exhibition begins spectacularly with the earliest extant woodblock print in world history: the frontispiece to the Diamond Sutra, commissioned in 868. This detailed and intricate image shows the Buddha discoursing with the disciple Subhuti surrounded by attendants and divine beings. The scroll bears the date, the equivalent of the western year 868, and a statement by a certain Wang Jie, who commissioned the scroll to ensure blessings to his family. The complexity of the composition and the refined technique suggest that this method of illustration was already well developed.

Buddhism was at the heart of the evolution of printing in China, for central to its philosophy was that the mass production of sacred texts and images was a way to receive blessings and to spread faith. Having become a state religion during the Sui dynasty of 589-618, Buddhism flourished during the Tang dynasty of 618- 906, though most of the earliest prints in this exhibition, including the Diamond Sutra scroll, were only discovered at the beginning of the 20th century, in a Buddhist cave near an oasis in Dunhuang in the northwest of the country.

About 100 prints from the museum’s vast collection are on show in this exhibition, leading us right through to the 21st century and to digital printmaking. There are gaps in chronology, but the 17th and 18th centuries are well represented, with both the establishment of commercial workshops and the development of printing in five or more colours. Florid prints of fierce-looking warriors were highly popular, since their symbolic function was to protect the household (pictured left: Bring-in-Emoluments Military Door Guard; Qing dynasty, 18th century).

About 100 prints from the museum’s vast collection are on show in this exhibition, leading us right through to the 21st century and to digital printmaking. There are gaps in chronology, but the 17th and 18th centuries are well represented, with both the establishment of commercial workshops and the development of printing in five or more colours. Florid prints of fierce-looking warriors were highly popular, since their symbolic function was to protect the household (pictured left: Bring-in-Emoluments Military Door Guard; Qing dynasty, 18th century).

In terms of popular imagery, there is surprisingly little that changes through the course of the 20th century, though the Modern Woodcut Movement in the late Twenties employs a new social realism to reach the masses and express the need for social and political change. During China’s occupation in the Sino-Japanese war (1937-45) artists created prints to exhort patriotism. Liu Lun, for example, edited a publication called Resistance Woodcuts and he is represented here by a realistically depicted print of wounded soldiers, executed as an appeal for international humanitarian support.

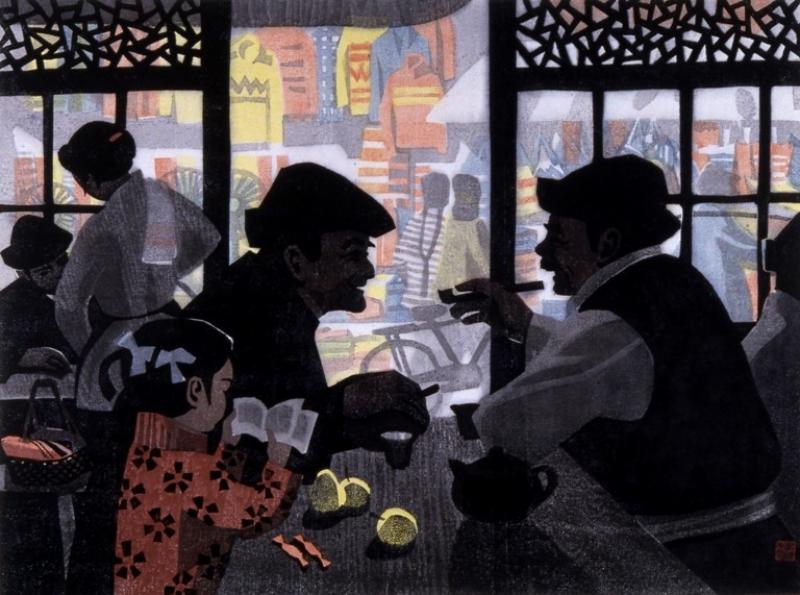

Heroic images of workers and peasants illustrated in a social realist style are not a particular highpoint in this exhibition, but later, more sensitive illustrations, such as Chen Yiming’s 1981 print Happiness (pictured above right), which depicts the weather-beaten face of a peasant while he is enjoying his pipe, are of a different order. This image was considered a milestone in Chinese contemporary art: the black and white contrasts, as well as the rough carving of the block to suggest the worn out features of the peasant, make it an extremely evocative image. Meanwhile, prints of everyday life such as Wu Jide's 1984 Chatting Over Tea (main picture top) evoke as well as idealise the life of the ordinary citizen.

This exhibition is impressive for the early achievements of printmaking technology. Slightly more difficult for the Western eye is how little seems to change in terms of imagery and the development of new and radical ways to depict a changing and evolving culture.

- The Printed Image in China is at the British Museum until 6 September

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment