The Super 8 Years review - Nobel laureate’s meditative self-portrait from home movies | reviews, news & interviews

The Super 8 Years review - Nobel laureate’s meditative self-portrait from home movies

The Super 8 Years review - Nobel laureate’s meditative self-portrait from home movies

French novelist Annie Ernaux fashions a new kind of auto-fiction

The French auto-fiction writer Annie Ernaux, now 82, was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature last year; now a fascinating new facet of her creative life has been released via her home movies.

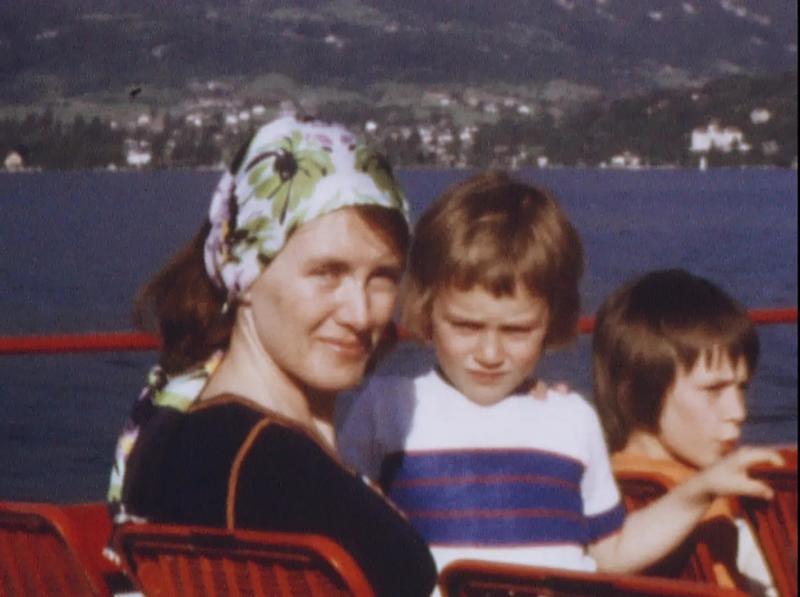

With her now grown son David Ernaux-Briot (who was three in the first of the films), Ernaux has fashioned a short (63-minute) documentary from the Super 8 footage her then-husband Philippe shot between 1972-81 – short, but rich, Ernaux’s narration lifting the everyday images into the realm of a cultural commentary with profound reach. It’s also a double portrait as these are the years that the Ernaux marriage foundered: like the ascending and descending buckets of Fortune described by Shakespeare’s Richard II, Annie’s writing career rises as her marriage declines.

When Philippe finally left Annie in 1982 he gifted her the reels, and the projector to play them on, while taking the Super 8 camera for himself. His appropriation of the filming emphasised a marital division that was there from the start, she explains, emblematic of his desire to be sole director of these records of family life. In fact, being relieved of filming freed her to pursue her writing in secret. At home, she was similarly helped out by her diminutive elderly mother, who was devoted to her grandchildren and stashed sugar lumps in her pockets to hand out to them.

We see Annie and her two sons first in consumer mode, proud of their Bell and Howell Super 8 camera, the “ultimate desired” consumer purchase, and keen, like good 1970s westerners, to travel the world. From the start, Ernaux’s commentary shows she is no ordinary tour guide. Philippe’s filming was born of happiness, but it was also a theatrical act, she senses, tinged with violence, an intrusion into family life. And what she sees – which isn’t there – is her drive to write going unfulfllled.

This is no ordinary family, either. Ernaux is a literature teacher, Philippe a city administrator of marked left-wing leanings. Their first filmed big trip is to Chile, ruled over by Allende’s socialist government and seen as a model republic. They are going there as “reporters”, she says. The people are poor, yet Ernaux doesn’t see their film as a record of social misery. The visit galvanises her into carrying out the promise she had made at 20 to avenge social injustice through her writing. Within 18 months, Allende has been assassinated and a right-wing puppet government installed by the US. We had images, Ernaux notes with poignant brevity, of a country that no longer existed.

Back home she feels the lure of the Ardèche, a rural area where her maverick sister-in-law lives with a young female companion in a house without running water or electricity. Ernaux’s children, she hoped, would feel there the power of a pre-industrial France. But only in the holidays. Grown-up Ernaux now knows what her sister-in-law couldn’t, and wouldn’t, see: the pollution targeting the area, where a power station was planned on the Rhône. All ignored the ecologists’ increasingly loud warnings.

The push-pull between 1970s “modern life” and what Ernaux knows now increasingly informs her commentary. We see the family in a replica rural “village” at M’diq, for example, sunning itself insouciantly by the hotel pool for three weeks; the public beach is used solely for washing horses. All is imitation, she states, even at the souks. Meanwhile, ruling Morocco unseen by them is despotic King Hassan II. The edge of contempt in her voice for her more complacent past self is affecting.

Perhaps the most surprising sequence is the 1975 trip she and Philippe make to Albania, “with mingled awe and repulsion”. In this newly opened up Stalinist-Maoist country, their “corrupt westerner” image is borne in on them by the compulsory bowl-shaped haircuts the men have to have on arrival, and the handout clothing they are made to wear – loose chinos for the men, dresses for the women. Their trip is zealously monitored; they see 2,000-year-old monuments but nothing of modern Albania, or modern Albanians, many of whom have now fled, she notes, while tourists flock to the beaches, still probably not seeing anything of modern Albania.

One intriguing section is Philippe and Annie’s 1976 visit to London, “the most exotic” of nearby countries for her, where she had been a miserable au pair in 1960. Sixteen years later she sees it as a "pre-Thatcher Eden” of parks with deckchairs, boating trips, and a Soho full of nightlife, pubs and porn.

As they constantly move from house to house, just as Philippe’s parents had, he films interiors and objects, as if, she says, trying to create a present that will lead to a future for them all. Ernaux’s super-sensitive seismograph then starts logging a new trend, indicating the hidden rumblings in her marriage: Philippe is shooting views and buildings, but not people, not her. By the couple’s visit to southern Spain in 1979, the fault lines gape open. While he ominously shoots the final stage of a bullfight, complete with the corpse being dragged off and the blood washed away, she is realising she is superfluous in his life. In 1981, as her novel The Frozen Woman is published, they make their last trip together; the next year her family unit implodes.

This is a treasurable “home movie”, a movie about home: how often Ernaux’s sense of it changed in those 10 years, how loosely it was anchored in firm ground. Having her distinctively calm, meditative voice as a narrator turns this amateur footage into one of her novels by other means.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

Add comment