Chroma/ Tryst/ Symphony in C, Royal Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Chroma/ Tryst/ Symphony in C, Royal Ballet

Chroma/ Tryst/ Symphony in C, Royal Ballet

The secret of great choreography is to surprise - can the young ones learn that?

A Balanchine on a mixed bill is a reminder of what a choreographer should desire to offer his audience: a specific new experience of art each time, not a repeated thumbprint in every ballet. Balanchine grew up in a borderless theatre country - jazz, music hall, Broadway, Cubism, Russian imperialism, folklore, classical piano studies, all soaked his personality and fed his imagination.

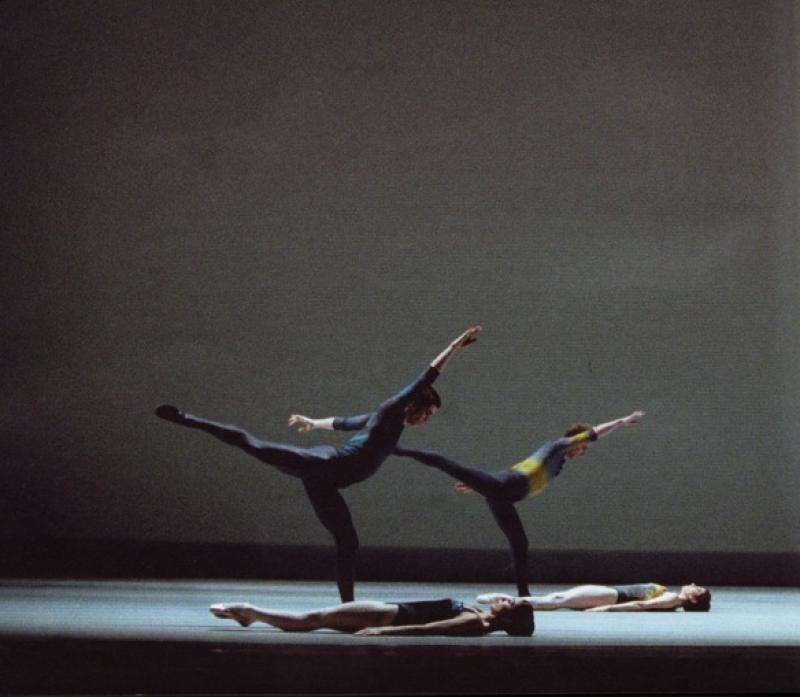

Not that there is much wrong with either McGregor’s Chroma - in its way - or Wheeldon’s Tryst. They are both young men’s works, but I still think that McGregor left his most idiosyncratic and stimulating invention behind when he moved from contemporary dance into the Royal Ballet, where his super-flexible alertness was transmogrified into the repetitious head-ducking and extreme extensions that make up almost all his ballets in the past few years. Chroma is the one with the celestial white light-box by John Pawson, and the unappealing little grey and beige vests and skimpy pants that must look sexy to somebody, I guess. (Right, Chroma photographed by Javier Galeano)

Why do I feel disappointed about where McGregor, 40 this year, has gone? What I remember from his early stuff in the 90s was the shock effect of apparently seeing bones searching out new spaces to move into under the skin, a sense of being ordered to look at a fresh, unused world of movement, and an insistent readjustment of senses and muscular destinations. This was very palpable in McGregor’s own strange, gangly and wholly compelling dancing. It was magnetic, I think because he was instinctually exploring his feeling of being different from his world.

Why do I feel disappointed about where McGregor, 40 this year, has gone? What I remember from his early stuff in the 90s was the shock effect of apparently seeing bones searching out new spaces to move into under the skin, a sense of being ordered to look at a fresh, unused world of movement, and an insistent readjustment of senses and muscular destinations. This was very palpable in McGregor’s own strange, gangly and wholly compelling dancing. It was magnetic, I think because he was instinctually exploring his feeling of being different from his world.

An ironing-out and intellectual acceptance process seems to have gone on with the Royal Ballet dancers, the crumples, creases and snags no longer look like intriguing accidents of experimental discovery, but permanently ironed in, like Issey Miyake pleats - a trademark. Chroma, made in 2006, has much the same feel to me as Infra and Limen, his Covent Garden pieces since it - in that, try as I might, I can’t sense any real difference in their movement qualities. If you took away their different sets and different musics (here it’s TV-score slush from Joby Talbot), you would still have McGregorist sort-of ballet, itchy, twiggy, leg-obsessed, jutting bums, nuzzling heads, a constant tease that reveals nothing at all about whether he is in a good or bad mood, or he feels this or that way about the music, or the occasion, or the time in his life. The personality that was so clarion in his early pieces is now subsumed in a sort of corporate brand, to my eyes.

In the performance I saw that might have been because Melissa Hamilton, with her rangy, bold body, made the movement look almost routine, so easily does she do it; and because both Brian Maloney and Rupert Pennefather looked contrastingly ill-at-ease. Olivia Cowley was interesting though, a black-haired junior who attacked her chances with a vivid scowl. There’s a glimpse of thrilling interpretation of McGregor in the recent Fred Wiseman documentary La Danse, where Paris Opera Ballet’s haughty, sophisticated ballerina Marie-Agnès Gillot steps down from her classical Parnassus with a surprisingly earthy appetite for his uninhibited, genderless athletic emphases. That kind of dramatic motivation of an interpreter's personal discovery is urgently needed to lift McGregor’s predictabilities back to the experimentalism they are supposed to represent, and Cowley showed flashes of it.

Wheeldon, 37, is a very different cause, very clearly a man who writes joined-up ballet of beautiful modern calligraphic script inspired closely by his music. His Tryst, made in 2002, ambitiously attempted to ride James MacMillan’s great bucking 1989 piece (composed for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra) and the integrity of the attempt carries it through the mountains. The costumes are nicer than the McGregor ones, dip-dyed dark bodysuits in blurry stripes of indigo, blue and red, against a foggy-grey sort of back drop that, in a very distant way, evokes Scottish highland air (Jean-Marc Puissant and Natasha Katz are responsible).

The dancers begin and end in synchronised skeins of serpentine wriggles that may bear some sort of birthing metaphor, and there are peremptory arm signals that might beckon to imaginary aliens but essentially mean only mystification to the watcher. These are modish tics that let the rest down, because Wheeldon’s real talent is the flexible marshalling of line and grouping on stage, the three-against-fours, the sense of architectural contrast between pillars (the ensemble) and featured ornaments (ballerina and partner). Sometimes he has the judgment to hold the dancers back to almost nothing in places where the music demands so much of the ear that the eye couldn’t cope with further decoration.

Sarah Lamb, bourreeing on like a streak of mist in the slow movement, didn’t let us down. Her delicate, pale aloofness is very different to the original Darcey Bussell’s self-possessed grandeur (left: Bussell and Cope in 2002 pictured by Asya Verzhbinsky), but this pas de deux is a proper dialogue with the eerie music and between a woman acquiescing out of interest to the stretchy challenges suggested to her by the man (Rupert Pennefather, looking much happier in this smooth neo-classicism). Light-bars slowly process electronically across the back, bringing scanners and radar to mind, but they remain two humans alert to a world that we are part of.

Sarah Lamb, bourreeing on like a streak of mist in the slow movement, didn’t let us down. Her delicate, pale aloofness is very different to the original Darcey Bussell’s self-possessed grandeur (left: Bussell and Cope in 2002 pictured by Asya Verzhbinsky), but this pas de deux is a proper dialogue with the eerie music and between a woman acquiescing out of interest to the stretchy challenges suggested to her by the man (Rupert Pennefather, looking much happier in this smooth neo-classicism). Light-bars slowly process electronically across the back, bringing scanners and radar to mind, but they remain two humans alert to a world that we are part of.

MacMillan conducted his own music, a gripping centre to an evening of three conductors, in which Daniel Capps led the Talbot for Chroma and Dominic Grier the sweet plangency and bubble of the Symphony in C composed by Bizet when he was just 17. I didn’t understand why Grier’s sweet and soaring tempo for the great Adagio evoked from Alina Cojocaru such over-emphatic leg swings and disturbance of the flow of these wonderfully large and sweeping arcs of Balanchine's, but Leanne Benjamin and Roberta Marquez both scintillated with confident allure in the ebullient first and third movements either side, abetted by the finesse of Johan Kobborg and Steven McRae.

And over and over you marvelled at the prolific imagination of Balanchine, the way he conjures up dreams, or crystals, or ballet classes, or networks of flutes and violins just by moving dancers around. The way he couldn't find one impulse the same as the last. Simple, really.

Watch Wayne McGregor explain the genesis of 'Chroma'

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Comments

...