The Fourth Tenor, Alfredo Kraus | reviews, news & interviews

The Fourth Tenor, Alfredo Kraus

The Fourth Tenor, Alfredo Kraus

The epicure's tenor remembered 10 years after his death

The great Spanish lyric tenor Alfredo Kraus died ten years ago, on 10 September 1999, celebrated by opera epicures, but less well-known to mass consumers of the Three Tenors publicity phenomenon. In 1992, during an engagement at Covent Garden, he spoke frankly to me about the deep issues - and dark politics - he felt were raised when populism took over from taste. This interview was published in the Sunday Telegraph.

When The Three Tenors got on stage together in Rome on the humid night of July 7, 1990, the world blinked with gratitude and then rushed to the shops to buy the video. Harmony being such an earth-moving event, it was only to be expected that when the Fourth Tenor injected a discordant note, there would be aftershocks. For Alfredo Kraus had the temerity to say that the get-together between Luciano Pavarotti, José Carreras and Placido Domingo wasn’t the concert of the century. It was, he added, not so much popularising opera as vulgarising it.

Well, thunderbolts flew in this war of vocal divinities. Pavarotti said people who didn’t like the concert were “stupid”, Domingo said Kraus only said it to get himself publicity, and Carreras said Kraus couldn’t appear in the Olympic Games opening ceremony which he is masterminding in July, so there.

Was that it? Just a few egos grown grotesquely oversized in the troposphere of opera, encouraged by a slavish industry and £10,000 per performance? Or was it really something to do with opera?

Alfredo Kraus says it was, yes, an argument vital to opera’s future.

Usually at this time of the year he is relaxing with his children and grandchildren at his country house on the Canary Islands. But thanks to that hardy annual the Pavarotti cancellation, Kraus is at Covent Garden instead, opening tomorrow night in Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’amore.

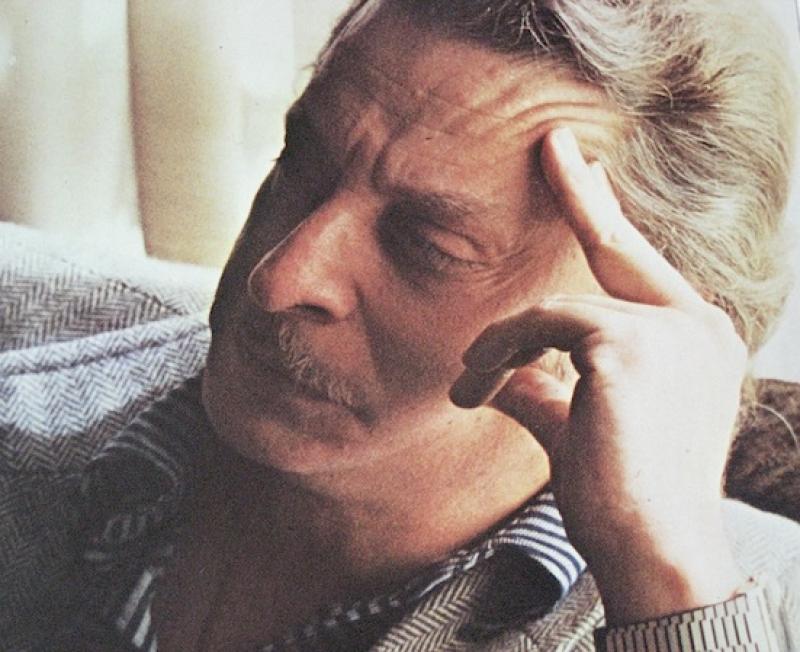

The "Nessun dorma" crowd may not have heard of Kraus but to opera-lovers he is a phenomenon: a grandfather who is still singing young lovers as ardently and classily as he did 36 years ago. Where Carreras and Domingo have voices of dark oloroso character, Kraus is the amontillado, the pale cream tenor favoured by epicures. It is easy to forget that he is Spanish, and not only because of that Viennese-sounding name: he is one of the country’s many pale-skins, auburn with hooded blue eyes. Small and neat, with the beaky nose and narrow moustache of a Grand Inquisitor, he looks like someone opera managers don’t mess with, but he is friendly and relaxed in our interview.

He is old enough to have sung when great sopranos were as thick on the ground as tenors seem today; he was Alfredo to Callas’s Violetta in La Traviata, Ferrando to Schwarzkopf’s Fiordiligi in Cosi fan tutte, Edgardo to Sutherland’s Lucia di Lammermoor. Always musical and polished, never capricious, without question he has earned his right to charge the same astronomic fees as the Three Tenors who gave the notorious concert at the Caracalla Baths in Rome in July 1990, and about which he is anxious not to be misunderstood.

“It was a journalist who started it - he asked me, ‘What do you think about the Concert of the Century?’ I said, ‘Which concert? Which century?” He said, the Caracalla one. I said that to call that the concert of the century was a bit much. It was a nice show, a very happy one, an easy concert for an easy audience, but the concert of the century should be on a different level, of music, of interpretation.

“And the journalist said, But at least it was attempting to give opera to the people. And I said, I don’t believe in this kind of popularity. If you want to give people knowledge of opera you don’t have an aria Puccini wrote for one tenor being sung by three. This is not popularising the music, it is vulgarising it.

“Well, they didn’t like it. But I am an artist, a singer. I am an intellectual - I was asked my opinion and I have the right to give it. I never said these singers are no good, they don’t have beautiful voices. What I said was to clarify this claim of ‘Concert of the Century’.”

Reaction was muted at first. Pavarotti harrumphed about “stupid” people criticising the concert, but Kraus’s wet blanket didn’t stop the Nessun Dormabile rolling one. Then six months later, January last year, someone phoned Kraus with the news that Carreras had been appointed artistic director of a gala featuring Spain’s formidable galaxy of opera stars, which was to be part of the Olympic Games inaugural ceremony in Barcelona on July 25 this year. And Kraus was not on the guest list, although naturally Carreras and Domingo were. To omit Kraus was incredible. As he states, without vanity, “I am the oldest singer in Spain still in activity, and I don’t think I am worse than them. Their voices are more beautiful than mine, but I am never less than them in my artistic results. If the Olympic event is a representation of Spain’s singers, I have to be there.”

Things then took a murkier turn. “I was told if I retracted in the newspapers what I said about the Caracalla concert they would invite me. Listen, I said, this is blackmail. This is not nice. I don’t retract anything.”

None of this was made public at first. The three Spanish tenors sang together as if nothing were wrong at a gala in Seville last May, but four months ago the Barcelona guest list came out and Carreras was challenged to explain Kraus’s omission. It was out of respect, he answered, respect for Kraus’s dislike of “the abuse of opera at mass media events”. Kraus saw red and charged out into the open. It wasn’t true, he told the press. Caracalla was the real reason. He had nothing against concerts, he carefully pointed out - “I also sing in stadiums, only I don’t say this is opera, this is culture. It isn’t. I do it because people want to hear Alfredo Kraus, they buy tickets, and I have more money.” Carreras, he said, was not telling the truth.

But he says the snub was only a side-issue. What makes him angrier is that the Spanish government seemed to be turning a blind eye to a takeover of Spanish opera by operatic “mafias”, as he calls them. For Carreras and Domingo are both the stars and organisers of Spain’s two most lavish and televised opera events - and in control of large public funds. It was no real surprise that Carreras got the Olympic gala to run - Barcelona’s musical scene has long been the fiefdom of Carreras, his agent Carlos Caballé and his agent’s sister, the soprano Montserrat Caballé - Catalonians all three.

But then Spain’s second international plum, Seville, fell into the lap of Placido Domingo. Last November, to launch its grand new opera house, Seville was treated to a new Tosca starring Mr Domingo and directed by Mrs Domingo (Marta Ornelas), assisted by Domingo fils. This family good fortune was capped by Domingo’s appointment to oversee the Expo 92 opera season which opened this weekend. Domingo has programmed 10 operas with himself in five of them.

“I never mentioned Domingo personally,” says Kraus, “but I accused the government that it is not right to put one singer in charge of an event run with public funds. In our socialist country the law doesn’t permit you to be at the same time singer and artistic director. This is not nice. This is the way fo facilitate discrimination. If we are all behaving like enemies, what if they put me in charge of a festival next year? It is stupid, very infantile, all of this.”

Well, all the best rows are always childish, and the Spanish press delightedly flagged the story “El Odio de los Divos” (nowadays there are more divos than divas), and public sympathy, so long with Carreras following his gritty fight back from leukaemia, swung over to Kraus. And under public pressure the inevitable has happened; Carreras has backed down, Kraus will be singing in Barcelona, and little José’s reputation as Mr Nice Guy will never be the same again.

Meanwhile in Buenos Aires a fortnight ago, Domingo defended himself against Kraus’s charges with the countercharge that Kraus himself was a publicity-seeker. Since then he has faced a heavy press bombardment over the 130million pesetas (£736,000) he is earning in his dual role as principal tenor and “musical assessor” in Seville.

Opera is going through an identity crisis, due to the proponents of a new quadratic equation which holds that Opera minus Elitism equals Popularity

ALMOST obliterated in all this hooha is Kraus’s original point. Opera is going through an identity crisis, due to the proponents of a new quadratic equation which holds that Opera minus Elitism equals Popularity. Hence the Pavarottis in the Park, the Dame Kiri World Cups, the Montserrat Caballé/Freddie Mercury anthems. But why is popularity so popular now, wonders Kraus. “Many years ago nobody used the word popularity about opera.” He thinks it is a folie de grandeur of democracy. “It’s political thinking: if you give everything to the people, why not the culture too? OK, I say but watch out. Vulgarising it doesn’t make it more popular. The problem is that people hear Caracalla and say, ‘Now I’ve heard opera, I’m cultured’. Culture needs education.”

He would seem to have a point. The Three Tenors recording may have sold 7million copies but last year opera attendances in Britain fell from 1,148,000 to 998,000. Kraus takes the prickly view that audiences and singers are getting lazy, depending on promoters and stage directors to spoon-feed every more Accessible productions.

“Theatre is not the movies. The audience must be more prepared, it must come to the opera in a different frame of mind from the movies. We cannot show them everything in the theatre, we have to give them the theatre’s simplicity, and they have to use their fantasy. And the singers also have to work harder to produce the freshness in opera through their interpretation.”

He says this feelingly. Even at 64, having deliberately specialised in a small repertoire (the Duke in Rigoletto more than 500 times), he still goes over and over parts he has done repeatedly. “A role is somebody’s life on a few pages. The more you think about them the better you can build their character. For instance, I like doing Nemorino [in L'Elisir d'amore - 200-plus performances] because it is very funny, but it difficult to get right. I normally am a bit aristocratic, a cultivated man, and he is a simple country man, and it is hard to be simple without seeming stupid. Many singers do Nemorino as if he is stupid but he is not - he is very clever, but in a simple way, like country people often are.”

Tenors have always been the biggest stars. It’s the most strange voice, the man with the high notes. If people want them they have to pay for them

And four Nemorinos will bring Kraus £40,000 or so - not bad compensation for a missed spring holiday. He was pleasant and frank about it. Was he worth £10,000 a performance? Was anyone?

“Yes, it’s worth it. It’s a free market. If you go to buy a painting you decide whether you think the price matches the value of it. If it’s too much you don’t go for it. Singers are something different, and tenors have always been the biggest stars. It’s the most strange voice, the most fascinating one, the man with the high notes. If people want them they have to pay for them.

“Anyway,” he added, thoughtfully. “The maximum today is not so huge. If you think that Caruso had $20,000 in gold for a concert… and he didn’t pay taxes! Besides, I like spending money. I don’t buy silly things but everything I have is expensive [he gestured to his sports jacket], my cars, my houses…”

I asked him if paying this kind of money to leading singers wasn’t bad for opera, when the idea of public funding for a minority interest is more and more under attack. Kraus, unsurprisingly, says it is not the star fees that are the problem, they’re only 15 percent of the costs; he blames the combination of rising production costs and the cult of personality for the twilight he sees looming over opera.

“It is beginning already: for the theatre organisers turning more and more to private money, it is much easier to find sponsors to pay for one big name, no expensive productions, no expensive ensembles. I think in a few years’ time opera in theatres may be finished and we’ll just be singing opera at concerts and recitals. Yes, just like the Three Tenors concert. That is a real danger.”

- This interview originally appeared in the Sunday Telegraph, 26 April 1992

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Comments

...