The private life of Stefan Zweig in England | reviews, news & interviews

The private life of Stefan Zweig in England

The private life of Stefan Zweig in England

His great novel 'Beware of Pity' is being staged at the Barbican. Who was Zweig, and the woman with whom he committed suicide?

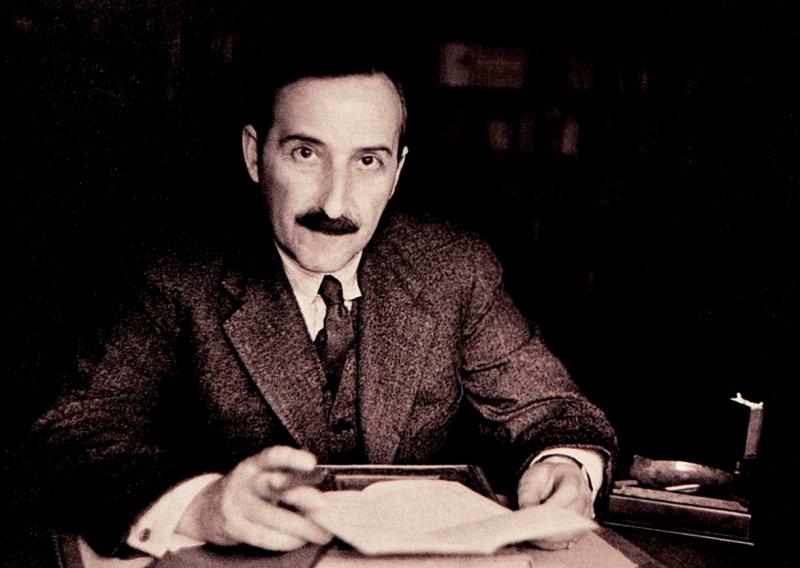

On 23 February 1942 at half past four in the afternoon in a secluded Brazilian hilltown called Petrópolis about an hour from Rio, a maid and her husband pushed at the bedroom door of a modest rented house. Despite the late hour, the tenants had not yet stirred. The door swung open to reveal, lying on the bed, a young woman in a cotton dress rolled over on her side, an older supine man wearing a jaunty moustache and a punctilious tie. The woman’s body was still warm.

Word of the suicide of the famous writer Stefan Zweig and his wife Lotte hastened as rapidly around the globe as any news could, barely two months after the United States’ entry into the war. For the previous two decades Zweig, an Austrian Jew born and raised in Vienna at the tail-end of the Hapsburg era, was perhaps the most translated author on the planet, certainly one of the most widely travelled and fêted. Many of his novellas and stories, most famously Letter from an Unknown Woman, would find their way onto the big screen. Zweig knew everyone. He corresponded for years with Freud and spoke at his funeral, wrote the opera Die schweigsame Frau with Richard Strauss, was friends with Mann and Rilke, Gorky and Joyce, Toscanini and Pirandello. Such was his stature that in 1932 he personally interceded to persuade Mussolini to commute the death sentence of an anti-fascist.

One is inclined to regard such giants dining at the top table of world literature as somehow beyond reach. Zweig in particular seems to hail from a mythical era he himself nostalgically refers to in the title of his memoir as The World of Yesterday. But sometimes these figures can come closer than one realises. In the case of this particular story, a great deal closer.

I first encountered Zweig before I had actually read him. I was writing a book called I Found My Horn about resuming the wind instrument I renounced as a school leaver. The focus of this midlife misadventure was Mozart’s third concerto for French horn, which at the end of a year’s practice I forced myself to perform to a paying audience. I discovered that the autograph manuscript was, oddly, in the British Library. The day before my performance, I received permission to inspect – to commune with - the piece of paper (pictured below) on which Mozart scrawled the very notes I had spent a year attempting to master.

The manuscript of K447 was part of the Stefan Zweig Collection. As is outlined in Three Lives, the superb biography by Oliver Matuschek, Zweig was an obsessive collector of historical manuscripts. He amassed documents featuring the handwriting of Leonardo da Vinci, of Handel and Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, Napoleon, Goethe and Nietzsche, even his and all Europe’s nemesis, Hitler. By an imperishable irony, he owned the manuscript on which Haydn set down the notes to the German national anthem. “Nothing,” he explained of his lifelong hobby, “can give an idea of the incomprehensible process of creation except, to some slight extent, handwritten pages.”

Soon after my book was published I received an email from my aunt, then in her late seventies. “Did you know you have a Zweig connection?” I did not. She offered a swift timeline. When Zweig and his wife Lotte died, his entire estate was inherited by Lotte’s next of kin, her brother Manfred. Manfred and his wife Hannah were in turn killed in a car crash in Switzerland in 1954, and the estate passed to their daughter Eva. Eva, my aunt explained, is her second cousin (and therefore also my mother’s). In other words, I spent a year obsessing about a composition by Mozart when the original manuscript was, as it were, already in the family. “It’s not the sort of responsibility that one particularly wants to inherit.” Some years ago I sat in the North London kitchen of Eva, a small woman with a watchful birdlike presence who is Lotte’s niece and my second cousin once removed. This was the first and only time she spoke to a journalist about Zweig and her aunt and, to preserve her privacy, she preferred to keep her surname concealed. Eva inherited the collection in her mid-twenties. She was now in her early eighties. “While the war was still on it wasn’t a burden,” she continued, “but as soon as the war finished it was a tremendous burden. My father was working as a doctor. My mother was looking after a lot of people. She took on the entire correspondence. Publishers from all the countries he was published in started writing and it became a very large problem. It was a full time job for her.”

“It’s not the sort of responsibility that one particularly wants to inherit.” Some years ago I sat in the North London kitchen of Eva, a small woman with a watchful birdlike presence who is Lotte’s niece and my second cousin once removed. This was the first and only time she spoke to a journalist about Zweig and her aunt and, to preserve her privacy, she preferred to keep her surname concealed. Eva inherited the collection in her mid-twenties. She was now in her early eighties. “While the war was still on it wasn’t a burden,” she continued, “but as soon as the war finished it was a tremendous burden. My father was working as a doctor. My mother was looking after a lot of people. She took on the entire correspondence. Publishers from all the countries he was published in started writing and it became a very large problem. It was a full time job for her.”

The rights to the books were sold off in due course, but the future of the manuscript collection remained problematic for several decades. Many had been retrieved from Austria, where Zweig had left them in the safe keeping of an antiquarian specialist, and most were stored in a bank vault until 1986 when they were eventually passed by Eva to the British Library. “I knew that this was not something that was meant for me,” she said. “Zweig had said it in some of his writings: he wanted it kept together and accessible to everyone.” Did she consider returning the entire collection to Vienna? “I wouldn’t have dreamt of it,” she said. “They forced him out. Quite a lot of the country supported the Nazis. They welcomed them when they marched in.”

If there is any sense of regret for the responsibilities posed by the inheritance, it is not reserved for Zweig nor, in particular, for Eva's aunt Lotte. In the story of Stefan Zweig, Lotte Altmann (pictured right) is die schweigsame Frau - the silent woman, the unknown woman. Who was she? Thomas Mann implicitly defamed her memory when lamenting Zweig’s suicide. “He can’t have killed himself out of grief, let alone desperation,” Mann railed. “The fair sex must have something to do with it.” Zweig’s first wife Friderike, a rather garish figure who more or less stalked Zweig until he succumbed, vengefully deleted Lotte from history when, with the Zweigs safely dead, she referred to herself in her US naturalisation papers as Zweig’s widow.

If there is any sense of regret for the responsibilities posed by the inheritance, it is not reserved for Zweig nor, in particular, for Eva's aunt Lotte. In the story of Stefan Zweig, Lotte Altmann (pictured right) is die schweigsame Frau - the silent woman, the unknown woman. Who was she? Thomas Mann implicitly defamed her memory when lamenting Zweig’s suicide. “He can’t have killed himself out of grief, let alone desperation,” Mann railed. “The fair sex must have something to do with it.” Zweig’s first wife Friderike, a rather garish figure who more or less stalked Zweig until he succumbed, vengefully deleted Lotte from history when, with the Zweigs safely dead, she referred to herself in her US naturalisation papers as Zweig’s widow.

Zweig and Lotte met in 1934. The author had sniffed the way the wind would soon blow in Austria and abandoned his splendid hilltop home above Salzburg to base himself in London. In urgent need of a secretary as he embarked on a biography of Mary Queen of Scots (inspired, as ever, by a document featuring her handwriting), he applied to the aid organisation for Jewish refugees. They recommended a well-educated young woman newly arrived from Germany and fluent in English and French. Friderike, by now being edged to the margins of Zweig’s life, later remembered Lotte in a memoir: “a very serious, not to say melancholy girl, who looked the very embodiment of the fate that had befallen her and so many fellow sufferers... But she overcame her frailty with admirable energy.” By the end of the year Lotte was no longer just Zweig’s secretary. No documents record the date her status changed. But a photograph of her in Monte Carlo taken in December 1934 by Zweig hints at intimacy. “Stefan Zweig pinxit,” he boasted in purple ink on the margin, like a Renaissance master authoring a work. Friderike discovered for herself in January 1935 when she burst into Zweig’s hotel room in Nice. “I have never seen a human being look so startled as this young girl roused from a state of deep drowsiness,” she recalled.

The rule was that at meal times we had to speak French. It was quite an effective way of keeping us quiet

The bond deepened as Zweig went about the complex business of divorcing his wife and winding up his affairs in Austria. Lotte was the perfect antidote to Friderike. “There are no love letters,” says Zweig’s biographer Oliver Matuschek. “He calls her Fraulein Altmann or Fraulein Lotte until the last days before their marriage. They had very similar characters, not loud or self-important.” Eva confirmed that “Lotte wasn’t a passionate person, but it was a very close and a very warm relationship.”

In London Zweig lived and worked in a service flat in Hallam Street, off Portland Place and convenient for his researches in the British Museum. Eva remembered it as “rather dark and slightly gloomy”. Whenever she visited she would turn into a sort of infant under-secretary. “In those days Lotte typed everything but she always had carbon copies and they had to be sorted and collated and that was the job I was given whenever I was around. I wasn’t aware of which books they were.”

As a growing tide of refugees asked Zweig for more assistance than he could provide, and Britain started to look dimly on enemy aliens, the Zweigs secured British citizenship and moved out of London. Three days after the declaration of war, they married and made an offer for a house on a steep hill overlooking Bath, much as Zweig’s old house had towered above Salzburg. Eva and a cousin called Ursula, a refugee recently arrived from Italy, were both evacuated there.

“We called them Onkel Stefan and Tante Lotte,” recalled Ursula, who still had a tinge to her accent on the phone. “I was thrown in at the deep end but they were very kind. Stefan was always interested very much in everything was going on - did we do our homework properly? He was a very humane person who cared a lot. He tried to foster our interest in various things. We each had some little duties to perform in the garden. We had a vegetable patch which we cultivated. They would come and see how it was getting on. He was very musical and we sometimes re-enacted parts of operas while Lotte played the piano.” Eva remembered being taken to Covent Garden by Zweig to see Don Giovanni, and being shown treasured items from the collection, above all Blake’s portrait of King John and Mozart’s catalogue of his own works. (Pictured below: Eva with Onkel Stefan and Tante Lotte)

“We called them Onkel Stefan and Tante Lotte,” recalled Ursula, who still had a tinge to her accent on the phone. “I was thrown in at the deep end but they were very kind. Stefan was always interested very much in everything was going on - did we do our homework properly? He was a very humane person who cared a lot. He tried to foster our interest in various things. We each had some little duties to perform in the garden. We had a vegetable patch which we cultivated. They would come and see how it was getting on. He was very musical and we sometimes re-enacted parts of operas while Lotte played the piano.” Eva remembered being taken to Covent Garden by Zweig to see Don Giovanni, and being shown treasured items from the collection, above all Blake’s portrait of King John and Mozart’s catalogue of his own works. (Pictured below: Eva with Onkel Stefan and Tante Lotte)

German was rarely spoken. Both cousins recalled a particular linguistic stricture. “The rule was that at meal times we had to speak French,” said Eva. “I think it has a double function. It was quite an effective way of keeping us quiet. But language was very important to him and he expected other people to be able to speak other languages too. Certainly French was absolutely expected.” He once wrote a charming letter to “Dear Evula” in which he glided between English and French, German and Italian.

For the rest of the time Zweig and Lotte would spend hours shut away in the library, he dictating and she typing. But there were other days, recalls Ursula, when this didn’t happen. “Tante Lotte would say, ‘Stefan is not in a very good mood today. You’d better not make much noise.’ She was a very caring person although her health was not good at that time already. She didn't make any fuss. As a child of 11 you wouldn’t know if a person was depressed.”

For the rest of the time Zweig and Lotte would spend hours shut away in the library, he dictating and she typing. But there were other days, recalls Ursula, when this didn’t happen. “Tante Lotte would say, ‘Stefan is not in a very good mood today. You’d better not make much noise.’ She was a very caring person although her health was not good at that time already. She didn't make any fuss. As a child of 11 you wouldn’t know if a person was depressed.”

Zweig’s depression and Lotte’s asthma are generally seen as the root of their joint suicide. The Bath ménage was broken up soon after the historic nadir of Dunkirk. Eva was shipped to safety (and three years of parentless misery) on America’s eastern seaboard. On her return, in 1943, she recalls bringing back some of Zweig’s precious manuscripts in her luggage. Ursula was reunited with her parents in London. In June 1940 the Zweigs sailed for the Americas. Their letters home in quirky English to Eva’s parents (now available in Stefan and Lotte Zweig's South American Letters: New York, Argentina and Brazil, 1940-42, co-edited by Oliver Marshall, another of Eva’s cousins) are often sprightly, but they are shot through with Zweig’s anxieties. These were variously caused by the round of endless lectures, lack of access to his library or manuscripts, grappling with Portuguese, his impending 60th birthday, the impossibility of seeing any new work published. They contributed to ever more regular bouts of what Zweig called “black thoughts”. “I pity poor Lotte,” he wrote, “that she has to go through all my sadness.” It was in this period that he wrote The World of Yesterday, a magnificent farewell to a vanished past which can be easily read as the longest suicide note in literary history.

Lotte laid it all out in a letter to Eva’s mother. “I am a little worried about him at present, he is depressed, not only because it is really no pleasure to lead such an unsettled life, always waiting what will happen the next day before making another short-term decision, but also because the facts of the war, which is now becoming a real mass murder, and its seeming endlessness weigh upon his mind.”

Lotte laid it all out in a letter to Eva’s mother. “I am a little worried about him at present, he is depressed, not only because it is really no pleasure to lead such an unsettled life, always waiting what will happen the next day before making another short-term decision, but also because the facts of the war, which is now becoming a real mass murder, and its seeming endlessness weigh upon his mind.”

And then there was Lotte’s ill health, manifested in endless nocturnal coughing. “Every night there are one or two dialogues between her and a dog in a house far away,” wrote Zweig from Petrópolis. She got thinner and thinner. Zweig complained of her loss of embonpoint: she was “only bones and coughs for weeks”. A summer spent in New York in 1941 and a failed treatment exacerbated her suffering.

But was this enough to warrant her participation in the final act? Zweig, a committed pacifist, had dabbled with the idea of suicide. In Bath he wrote that, against the possibility of a German invasion, he had “already prepared a certain little phial”. “He was thinking about suicide during World War One,” says his biographer Oliver Matuschek. “He had depression in Salzburg. He even asked Friderike to commit suicide with him. There must have been an idea for a joint suicide in his mind.”

The penultimate letter to London, 11 days before their deaths, speaks of keeping the house on for the winter. Then on 21 February Lotte wrote to her sister-in-law. “Dear Hanna, Going away like this my only wish is that you may believe that it is the best thing for Stefan, suffering as he did all these years with all those who suffer from the Nazi domination, and for me, always ill with Asthma.” In the same letter Zweig lays the same stress: “you would understand us better had you seen how Lotte suffered in the last months... we decided, born in love, not to leave each other.” She was 34.

Two of Zweig’s most celebrated biographies told of queens - Marie Antoinette and Mary Stuart - who were executed. Did Zweig execute his own queen? “I don’t think I was terribly surprised,” said Eva, who was 12 when she was told by the woman running the children’s home where she was living. “I think you’ve got to put yourself into the war situation. People were dying right, left and centre. I never really took in how young she was till much later. The asthma never stopped her. But she wouldn’t have wanted to go on living without him.”

Nearly 70 years on from Zweig’s death, only one portion of the archive remains in Eva’s possession: the many books and effects Zweig left behind in Bath. They include his pipe and initialled walking stick. There is a photograph of Eva and Ursula gardening with Lotte, her long face and wide-set eyes iterated across generations of my family tree. Zweig’s tiny address book has the contact details of Freud, HG Wells and Bernard Shaw written in Lotte’s hand. A copy of Ulysses is signed by Joyce to Zweig.

The books, including editions of Zweig’s works published in many languages from Croatian to Japanese to Esperanto, are housed in the glass-fronted bookcases which Zweig had shipped from Salzburg to Bath. The most personal of them are first editions signed by Zweig to his new young secretary and lover. “Miss Lotte Altmann,” Zweig writes optimistically in Mary Stuart, “with sincere thanks for her assistance with this and hopefully many other books.”

- Beware of Pity at the Barbican Theatre from 9 to 12 February as part of the Schaubühne season. It will be live-streamed on Complicite's website and YouTube channel at 3pm GMT on Sunday 12 February and available to view until 26 February

- Beware of Pity, The World of Yesterday and other works by Stefan Zweig are published by Pushkin Press

Buy

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Stefan Zweig's non-fiction

Very interesting article. In

A superb writer, whose work,