Carmen, Royal Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Carmen, Royal Ballet

Carmen, Royal Ballet

Carlos Acosta's Covent Garden swansong proves tragic in all the wrong ways

Carlos Acosta is that rare 21st-century phenomenon – a performer who has become a household name without the help of reality TV. Even people who run a mile from ballet know the story of the Havana slum boy made good through perseverance and pure talent, from countless primetime documentaries as well as a self-penned book and stage show.

All this has meant that Carmen, his swansong project before his planned retirement from dancing next year, has been borne along on a wave of goodwill. A 60-minute retelling of Mérimée’s story, stripped to its blazing essentials and set to a fresh orchestration of Bizet’s tunes – what could possibly go wrong? Almost everything, in the event. A treatment that set out to be thoroughly modern feels oddly old-fashioned, with its lace-undies sexuality and clunky eclecticism. The familiar score gets pulled about something rotten, with additions from off-stage choir, on-stage flamenco guitars and a line-up of Latin percussion complete with bongos. Now and again the dancing cast is infiltrated by opera singers – not a bad idea in itself, but woefully lacking continuity or point. On opening night there were communication difficulties, too, between the singers and the conductor, Martin Yates, whose orchestration it was.

Yet the story is clearly told. Whereas the maverick Mats Ek, whose cartoon-brash Carmen was loathed as much as it was loved at the Opera House, made much of the subplot, Acosta cuts the action to its essentials. If the remaining three main characters retain any complexity at all, it’s by dint of nuanced acting – particularly from Acosta himself as Don José, a man who looks like a loser from the moment he allows Carmen to unbutton his military jacket.

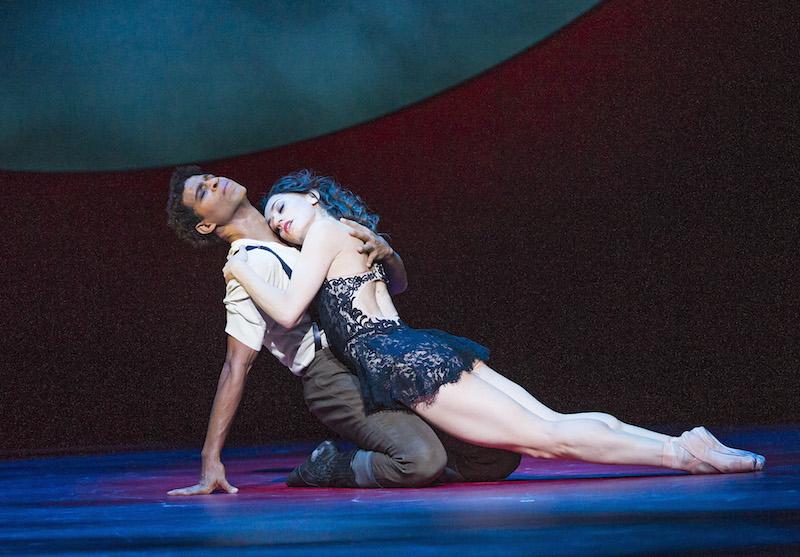

Carmen and Don José’s grappling duets looked beetle-small on that huge stage

Marianela Nunez cannot be faulted on her commitment to the title role, so it seems a touch unfair to admit to disliking the character increasingly as the ballet progresses. But Carmen’s relentless tigerishness around men, her insatiability, is frankly tiresome, and you find yourself longing for her comeuppance. In the opera a thin layer of remove is created by the fact that seductiveness must be suggested through the voice. In a ballet, in this ballet anyway, the dancer’s body too readily assumes the postures of sex, and it’s too much. What’s more, Carmen and Don José’s grappling duets looked beetle-small on that huge stage. They may work better on screen, in close-up.

Federico Bonelli’s preening toreador is very stylishly and amusingly done: on the whole, Acosta’s choreography for male characters is sharper than that for the women. Yet for the ensemble he fails to come up with any memorable ideas at all. Scooting about on wheeled chairs is old hat; girls standing astride their men and sticking their bottoms out is simply crass. Tim Hatley’s designs are mostly bold and straightforward, if unoriginal. Did anything ever happen in Spain that wasn’t under a blood-red lunar eclipse?

Earlier, the evening had been a five-star affair, with a first Royal Ballet revival of Viscera, Liam Scarlett’s most accomplished abstract work to date. The piece takes its cue from a piano concerto by the American Lowell Liebermann that sounds like Shostakovich on speed. Scarlett matches its stabbing strings and tumbling piano clusters with fierce pirouettes, flashing six-o’clock legs and lifts that drop like a stomach in a lift. Its melting middle movement showed Leticia Stock to be a fast-rising talent.

The class act continued with a brace of American pas de deux that shone like two bright stars. Many will cherish the memory of Carlos Acosta in Jerome Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun. Here it was the turn of newly ultra-fit Vadim Muntagirov to display his bare torso to best effect in the invisible dance studio mirror. The nice conceit is that the audience is that mirror, as the boy and his dream girl (Sarah Lamb, pictured above) limber up and inspect their line. Even when they finally touch they keep an eye on how cute they look together. Archly witty and beautiful, delivered with a drop of ice.

The class act continued with a brace of American pas de deux that shone like two bright stars. Many will cherish the memory of Carlos Acosta in Jerome Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun. Here it was the turn of newly ultra-fit Vadim Muntagirov to display his bare torso to best effect in the invisible dance studio mirror. The nice conceit is that the audience is that mirror, as the boy and his dream girl (Sarah Lamb, pictured above) limber up and inspect their line. Even when they finally touch they keep an eye on how cute they look together. Archly witty and beautiful, delivered with a drop of ice.

The Tchaikovsky pas de deux is a George Balanchine genuflexion to high Russian classicism set to music discarded from Swan Lake. Long-limbed Natalia Osipova would have been an intriguing match for neat Steven McRae, but she had taken herself off to Moscow to be replaced by tiny Iana Salenko, an increasingly regular RB guest with superbly neat feet and the spring of a baby gazelle. Together, they soared. What a pity that Acosta’s Carmen never achieved take-off.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Osipova was reported to be

'....had taken herself off to