Q&A Special: Ballet Guardian Tony Dyson | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Ballet Guardian Tony Dyson

Q&A Special: Ballet Guardian Tony Dyson

It's been a tricky thing to devise the preservation of ballet genius Frederick Ashton's works, as his heir explains

On Saturday one of the master ballets of the Royal Ballet genius Frederick Ashton returns to the Covent Garden stage, Enigma Variations. Its owner is an architect, one of Ashton’s last friends, and one of the handful to whom the choreographer left the small number of ballets he felt would be of financial benefit to them when he died in 1988.

Now that architect, Tony Dyson, has succeeded in constructing a Foundation to protect the remains of Ashton’s ballets and assemble as much as possible to enable their best-possible performance - and possibly even restoration of a couple - for future generations. It will coordinate the wishes of the owners with a large research project to find films, photographs, verbal reminiscences, writings, opinions, first-hand experience of the ballets’ creation, all the materials possible to prime future stagers with understanding of these beautiful, delicate works of dance theatre.

The necessity has become increasingly urgent, with the deaths of several of Ashton’s heirs, most recently Alexander Grant, owner of the world-famous comic ballet La fille mal gardée. Margot Fonteyn’s two ballets are now owned by non-ballet-world descendants, the bequests to Brian Shaw, Michael Somes and Grant have been or will be handed on, while Sir Anthony Dowell, former Royal Ballet director, and Ashton’s nephew Anthony Russell-Roberts, former Royal Ballet administrative director, retain the Royal Ballet’s close association with other works.

The Royal Ballet, the company of which Ashton was both chief choreographer and, from 1963 to 1970, artistic director, is at the heart of the new Foundation. Russell-Roberts, current Royal Ballet director Dame Monica Mason, director-designate Kevin O'Hare and associate director Jeanetta Lawrence are trustees alongside Tony Dyson, and Felicity Clark, a trustee of the Royal Opera House Benevolent Fund, completes the Board. Christopher Nourse, its executive chairman, is a former administrative director of the Royal Opera House Trust.

However, with so many dispersing interests, making common cause has been by no means easy. Here Tony Dyson explains to theartsdesk how the Ashton Foundation is intended to become British ballet’s finest artistic asset, a treasure trove of the facts and theatrical knowledge that makes a ballet live again long after its creation.

Fred really wanted the right people to have them. It was as important that the heirs were apt people as that they got some money

ISMENE BROWN: Ashton didn’t make it easy. His proclaimed attitude to the future of his work was “Fuck posterity!”

TONY DYSON: He often said things like that and you had to read between the lines. In reality, of course, he thought very hard about the whole thing. What he said to me was, "I want my friends to benefit from my work. Rather than organisations." He didn’t bear grudges really, but he would refer to having been sacked at one particular stage.

By the Royal Ballet?

By the Royal Ballet?

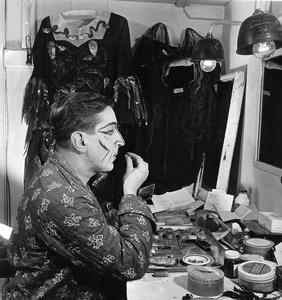

Exactly. (Pictured left, Ashton making up as Carabosse in The Sleeping Beauty, 1951 © Roger Wood Collection/Royal Opera House.)

Balanchine also did not leave his ballets to his company, New York City Ballet, but individuals.

Yes, and he left them to a greater number of individuals, which is why the Balanchine Trust was formed. It's the Balanchine set-up that inspired the setting up of the Frederick Ashton Foundation.

The Brits haven’t been very good at looking after Ashton since his death. Lynn Seymour said to me many years ago that there should be a British ballet trust, which took the key works out of the Royal Ballet and placed them in an independent entity.

In one way I disagree. I believe there has to be a company at the heart of any organisation aiming to promote the work of a choreographer and in the case of Frederick Ashton’s ballets, it's my hope that, subject to the ballet owners’ cooperation, the majority of those who will be trained to stage the ballets in the future will come from the Royal Ballet. They would make full use of the Ashton Foundation's coordinating role in promoting and making available film and written archive, academic study, filming of the masterclasses, ballet re-creations, etc. Jeanetta Lawrence’s involvement is to help us to earmark particular people now to stage the particular ballets. That is a good step in the direction of being able to connect with those who are going to be trained up to stage the ballets in future. It’s totally subject to the owners, but only two of them actually stage ballets themselves, and in their case, they call the shots. But there will be a parallel scheme alongside to ensure people are in place to take on the staging in the future. It’s the best you can do.

How many ballets have moved on from first-generation heirs to second-generation?

With the passing of dear Alexander Grant, only Anthony Russell-Roberts, Anthony Dowell and myself remain from those owners named in Freddy’s will. Anthony Dowell and Wendy Ellis Somes, Michael Somes's widow, stage their own ballets. When Margot died, she left Daphnis and Chloë to her brother Felix and Ondine to [her husband] Tito’s daughter. Then Felix died, and now Lavinia Hexham, his daughter, owns Daphnis and Chloë (pictured right, the 1951 original cast, Michael Somes and Fonteyn © Roger Wood Collection/Royal Opera House). But I realised that from Phoebe Fonteyn onwards, nobody had any idea what to do. So the ballets of subsequent heirs are staged under contracts, administered by agents, with the Royal Ballet making the artistic decisions. The heirs were happy with that because they were touched to have been left the income, they continue to own the ballets, and they get the royalties minus the 10 per cent for the agents who organise it. And although the artistic decisions are now made by the Royal Ballet about who sets it, who coaches it, I wanted the work to end up in a pocket within the Royal Ballet - which is the Foundation.

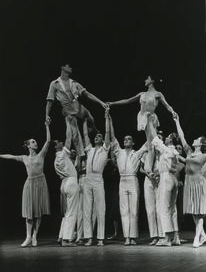

With the passing of dear Alexander Grant, only Anthony Russell-Roberts, Anthony Dowell and myself remain from those owners named in Freddy’s will. Anthony Dowell and Wendy Ellis Somes, Michael Somes's widow, stage their own ballets. When Margot died, she left Daphnis and Chloë to her brother Felix and Ondine to [her husband] Tito’s daughter. Then Felix died, and now Lavinia Hexham, his daughter, owns Daphnis and Chloë (pictured right, the 1951 original cast, Michael Somes and Fonteyn © Roger Wood Collection/Royal Opera House). But I realised that from Phoebe Fonteyn onwards, nobody had any idea what to do. So the ballets of subsequent heirs are staged under contracts, administered by agents, with the Royal Ballet making the artistic decisions. The heirs were happy with that because they were touched to have been left the income, they continue to own the ballets, and they get the royalties minus the 10 per cent for the agents who organise it. And although the artistic decisions are now made by the Royal Ballet about who sets it, who coaches it, I wanted the work to end up in a pocket within the Royal Ballet - which is the Foundation.

So if, say, the Paris Opera Ballet wanted to put Ondine on or the Cubans planned to do La fille mal gardée would they approach the Ashton Foundation or the heirs?

Christopher Nourse, the Foundation’s executive director, is also the secretary of the Ashton Trust, the association of Ashton ballet owners. Christopher has a desk in the Royal Ballet office, so one way or the other, enquiries will get through to the owners or their agents, as appropriate.

What’s happened to the bequests to the late Brian Shaw [Les patineurs, 1937, and Les rendezvous, 1933]?

Brian left his ballets to Derek Rencher [former Royal Ballet principal dancer].

So several ballets probably go safely from an in-house heir back to the Royal Ballet academic establishment.

Yes.

Did Ashton try to read in his crystal ball that some ballets would be worth more than others?

He thought Fille would outlive him. He obviously left friends the 12 ballets that he thought would endure and benefit them. But his favourite ballet, Scènes de ballet, he didn’t leave to anybody, because then he didn’t think it would bring in much money. He left it along with the rest to Anthony [Russell-Roberts] but I’ve thought since then that he was fully aware that if anybody was going to promote the rest of his work, his nephew Anthony would be the best person. And Scènes has actually had more performances than many of them (pictured left, Scottish Ballet's Claire Robertson and Adam Blyde in Scènes de ballet © Merlin Hendy/Scottish Ballet).

He thought Fille would outlive him. He obviously left friends the 12 ballets that he thought would endure and benefit them. But his favourite ballet, Scènes de ballet, he didn’t leave to anybody, because then he didn’t think it would bring in much money. He left it along with the rest to Anthony [Russell-Roberts] but I’ve thought since then that he was fully aware that if anybody was going to promote the rest of his work, his nephew Anthony would be the best person. And Scènes has actually had more performances than many of them (pictured left, Scottish Ballet's Claire Robertson and Adam Blyde in Scènes de ballet © Merlin Hendy/Scottish Ballet).

Perhaps Fonteyn drew the short straw in hindsight, because Daphnis and Ondine can only really be done by companies with really good orchestras and great dancers. They’re almost like her personal jewels, because they don’t travel as well as Fille.

I think he was thinking more that those were totally logical bequests to her, and he left her something like £30,000 as well, so he was totally aware of her situation… Anyway it had been revived before he died, with Jonathan Cope and Maria Almeida, so it was current at that time.

He could have left her Cinderella.

The reason he left Cinderella and Symphonic Variations to Michael Somes was that that fits too. I’m sure he thought hugely about it. Worked it all out. Those were the ballets that he thought would bring them money and he also liked his own work to be successful, so he also wanted the right people to have them. It was as important that the heirs were apt people for the work, as that they got some money.

I was the only non-dancer of the heirs. He told me he was leaving me Enigma, and asked me what other ballet would I like? As I’d been on the board of Rambert, I thought sentimentally I’d like Capriol Suite [1930, made for the Marie Rambert Dancers]. He said, "Oh no, that won’t get you any money." But I heard no more until the will was read. I always thought he’d left me Monotones for the money. But Lynn Wallis, who stages it for me, said to me, "Actually this is an extraordinary ballet to leave to an architect, because of its pure lines and construction" (pictured right, Birmingham Royal Ballet in Monotones II © Steve Hanson/BRB). And then I realised, typical Fred, it was completely apt - just as Enigma was apt, because I was an architect from Worcester, and there’s an architect in Enigma, Troyte Griffith, and of course Elgar was from Worcester.

I was the only non-dancer of the heirs. He told me he was leaving me Enigma, and asked me what other ballet would I like? As I’d been on the board of Rambert, I thought sentimentally I’d like Capriol Suite [1930, made for the Marie Rambert Dancers]. He said, "Oh no, that won’t get you any money." But I heard no more until the will was read. I always thought he’d left me Monotones for the money. But Lynn Wallis, who stages it for me, said to me, "Actually this is an extraordinary ballet to leave to an architect, because of its pure lines and construction" (pictured right, Birmingham Royal Ballet in Monotones II © Steve Hanson/BRB). And then I realised, typical Fred, it was completely apt - just as Enigma was apt, because I was an architect from Worcester, and there’s an architect in Enigma, Troyte Griffith, and of course Elgar was from Worcester.

Americans have had a lot to do with calling for the preservation of Ashton.

Yes, Lincoln Kerstein included Enigma Variations in his book 100 Masterworks, and during his long career Freddy had huge success in America and often said that it was recognition in America that eventually brought about his success in the UK.

People say about Balanchine stagings by his great stars, Peter Martins, Suzanne Farrell and Edward Villella, that there are great differences between their productions.

Absolutely so. And you hear with musical interpretations on record the huge difference over 50 years. I became aware early on that interpretation was part of the process of staging a ballet. When Freddy said he was leaving me Enigma I said to him, "What will I do about the staging?" He said, "Michael [Somes] or Alexander [Grant] will help you out." But what was interesting was that I had the opportunity in later years of sitting with Michael, when Alexander had put Monotones on, and with Alexander, when Michael had put it on, and they were highly critical about each other! And that was a ballet for only six dancers.

Where would the differences occur? Most people think about choreography that the steps are set.

There is more to recreating an Ashton ballet than simply reproducing the steps. From what I have seen, creating a ballet can sometimes be an extraordinarily complex process. The choreographer works with the first cast, talks to them, asks them to think this, try that, why don’t they try this, oh that’s not working, or they forget a bit, so they make something else up. There’s this huge input going in over a number of weeks, with only a minute or two of choreography being achieved at each rehearsal. Then you expect a different lot of people to do it a year later for a revival without all that input but still finding the essence of what the original cast and the choreographer achieved.

So you are looking for a stager who can give that input somehow. Marguerite Porter told me when she was playing Natalya Petrovna in A Month in the Country, Fred gave her the script, and then told her what she was thinking when she came through the door and found Belyaev and Vera embracing: “You peasant!” That gave her the impulse for what to do. But when someone teaches from a video and a choreographic text, you don’t have that. The choreologist plays a huge part in the process of communicating the choreography as notated in the score but the stager needs to find that extra step in understanding.

I remember at Rambert watching Glen Tetley taking Mark Baldwin through Pierrot Lunaire, and Glen didn’t mention a step once. He told him what he was meant to be thinking, how he had to get from here to there within the musical phrases, how he was meant to react. He was working for a good hour like that, implanting the essence in Mark’s mind.

When Enigma was put on by BRB at the Met in New York in 2004, Desmond Kelly did it with Patricia Tierney and it got fantastic reviews - that’s the way to do it (pictured left, Birmingham Royal Ballet's Joseph Cipolla and Silvia Jimenez as the Elgars, photo Stephanie Berger).

When Enigma was put on by BRB at the Met in New York in 2004, Desmond Kelly did it with Patricia Tierney and it got fantastic reviews - that’s the way to do it (pictured left, Birmingham Royal Ballet's Joseph Cipolla and Silvia Jimenez as the Elgars, photo Stephanie Berger).

With Monotones I’m lucky, because Lynn Wallis can do exactly what I’ve just said as well as being able to record all the nuances in the choreographic score, and also knowing practically about the weight shift needed to achieve something.

Whatever Ashton had in mind when he said "Fuck posterity!" - and perhaps indeed he might not have meant it - but actually 23 years after his death a lot of his work is considered lost. When I interviewed Anthony Russell-Roberts about this 12 years ago, he essentially dismissed the possibility of recovering almost everything he owned. He said Sylvia’s gone, Dante Sonata’s gone. I also remember Anthony Dowell telling me in the Nineties that Ashton wasn’t box office. In fact David Bintley [Birmingham Royal Ballet artistic director] brought Dante back, and the Royal Ballet has since brought Sylvia back.

Freddy was philosophical about what would happen to his work. He told me he had noticed that when people died, after the initial tributes, there was normally a loss of interest for a few years and then interest would revive and I think he has been proved right. Since he died, Scènes de ballet has become very popular, Anthony's also made a staging of the film Tales of Beatrix Potter, and revived Sylvia, which Fred thought could never be done. And there'll be a look at Foyer de Danse (1931) next year. So actually he was canny in how he left the residue.

The opportunity is certainly there for owners to bequeath their ballets to the Frederick Ashton Foundation

What control can the Foundation have over the future ownership?

For now the Foundation is set up allowing for the current ownership situation but the opportunity is certainly there for owners to bequeath their ballets to it if they wish. Who knows what the future will bring?

Has it helped in doing this that you are “outside” the ballet world?

It helps that I’m a conservation architect! I have to deal with this kind of thing in buildings, the loss of historic detail, getting a sculptor to take on the restoration of a medieval or 17th-century carving, and so for me this kind of conversation is second nature. I’m aware of how repro doesn’t work, and why repro doesn’t work.

We see a lot of rotten “classical” productions which are no better than bad repro! When you were looking at the different trusts, how many models were there to look at? Balanchine, José Limon, Antony Tudor, Martha Graham…?

For the Ashton Trust, which I also chair, I found out all I could from the various websites and met the lawyer Paul Epstein, who established the Balanchine Trust, a number of times, with Anthony Russell-Roberts. The Tudor Trust I had come across at the Rambert Dance Company, when I was on the Board and [artistic director] Richard Alston had asked Maude Lloyd to have a look at Sally Gilmour’s staging of Tudor’s Dark Elegies. Maude, who had been in the original production, disapproved of a number of changes Sally had made and reported the company. It was all settled out of court but was quite a costly exercise.

What was the difference?

When Sally came along, Tudor had adapted Maude's role. One thing I remember Fred saying to me over and over again, "It’s got to be effective." He didn’t give a damn about sticking to the letter of the script. And I imagine it was the same with Tudor, that Sally Gilmour’s different qualities gave opportunities that he hadn’t had with Maude. I think they were both right in their own way, but you had to choose who to go with. I don’t think an amalgam of the two would be any righter.

Who will decide in future on the “right” version of any ballets taken into the Foundation? How many people will you allow to be the oracles? The Balanchine Foundation have a lot of people, three or five stagers per ballet sometimes.

I don’t think we’ve thought that far yet. We have only just started the Foundation with one aim being to train up the stagers in the future. Currently those who stage the ballets are the owners, those nominated by the owners or their agents. There is a long way to go.

Is there an Ashton style that you can define? Or does it change from ballet to ballet, from person to person, from period to period? The Balanchine idea is somehow that there is a definable physical style for a movement.

That’s why the Foundation’s connecting with the academic is so important, because in that way there’s the chance that people in future will be able to refer back and see “why” as well as “what”. It might be that in half an hour’s talk there’d be five seconds of insight about how to do Brian Shaw’s wiggly bit in Symphonic Variations and you can record that (pictured left, the 1946 Symphonic Variations original © Roger Wood Collection/Royal Opera House). That’s why the Foundation’s connecting with the academic is so important - for instance, by coordinating where the different films are, getting the stuff off the BBC - telling people where these things are, so they can see the earliest materials, such as the early film of Fille, with Nerina, Blair, and the film of Ondine, which, though it was edited for TV, still has a lot. In that way there’s the chance that people in future will be able to refer back and see the development of the Ashton style in the context of the different generations of dancers.

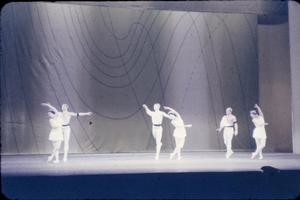

That’s why the Foundation’s connecting with the academic is so important, because in that way there’s the chance that people in future will be able to refer back and see “why” as well as “what”. It might be that in half an hour’s talk there’d be five seconds of insight about how to do Brian Shaw’s wiggly bit in Symphonic Variations and you can record that (pictured left, the 1946 Symphonic Variations original © Roger Wood Collection/Royal Opera House). That’s why the Foundation’s connecting with the academic is so important - for instance, by coordinating where the different films are, getting the stuff off the BBC - telling people where these things are, so they can see the earliest materials, such as the early film of Fille, with Nerina, Blair, and the film of Ondine, which, though it was edited for TV, still has a lot. In that way there’s the chance that people in future will be able to refer back and see the development of the Ashton style in the context of the different generations of dancers.

The other problem is the jealousy between the staff and anybody who comes in to coach. Because they all have strong ideas about doing it.

Is a successful revival defined by the fact that it looks like the piece that was created?

The choreographer can play with their own work, but how do you get someone who isn’t the choreographer to have that sort of authority?

No, I don’t think so. The problem is that if the choreographer is alive, he or she can play with their own work. Some people would say pieces are not always improved by that - as in Balanchine’s various changes to Apollo. Most choreographers do want to stick to the original, but adapt to the new artists in front of them, with different qualities. But how do you get someone who isn’t the choreographer to have that sort of authority? Otherwise you can only get a deadpan reproduction. You don’t want people copying the steps without understanding the script or the audience will say, "Oh, that’s just a pale shadow."

That’s what classical musicians do - they play from the script. Marie Rambert wrote long ago and Peter Wright was telling me once that dancers should read notation and know the steps before they come into the studio.

It’s very difficult in ballet. If you have a John Eliot Gardner or Harry Christophers, they are creating these wonderful interpretations with totally different sound.

With the Ashton Foundation will you essentially be able to insist on the notated text? This phrase of steps, those three pirouettes, that angle of développée.

Of course, it’s in the notation. The owners have their ballets staged under contract and it is in the development of the contracts to cover these matters that the control lies. But for instance I was rung up by Desmond Kelly when he’s staging Enigma who says, "I’ve got two boys who turn to the right, but of course Anthony [Dowell, the original Troyte] turned to the left." And I said, "Actually, it stands on its own, so it doesn’t matter." He said, "That’s what I hoped you’d say!" But it could be absolutely crucial that the turns take you to a certain point on the stage, and then you wouldn’t give way, and you’d have to recast. All the ballets are performed under contract, time-limited. It’s not just about royalties. Things can only be done for three years, then they have to be looked at from scratch.

What about the power to redesign sets and costumes?

Again, this can be defined in the contracts used but the Foundation will be able to suggest who to go to for advice if it is needed, whether musical or in connection with design. We’ll have associates to advise on each project.

So the Foundation will have the power to recommend the designers and conductors as well. But what if a foreign company wants to use their own hotshot designer or their own conductor?

Then they’d have to pay for somebody to go out and see what this person was like, hear a couple of concerts or look at a couple of productions. I’ve turned down more requests for Monotones than I’ve allowed because of this kind of thing. The idea is that you have to be of a certain standard as a company to perform the work.

The idea is that you have to be of a certain standard as a company to perform the work

The Balanchine Foundation once forbade the Royal Ballet from putting on a cast. Would the Ashton Foundation do so?

As happens currently, the responsibility for agreeing casting normally lies with the person staging the ballet and this can be enforced under the contract. But you don’t want it to be like the Martha Graham situation, which just reproduces. It’s weak.

But one sees what’s happened to old classics, remade again and again, so there’s precious little left of the original, and one wonders, do people want to recreate the original? Opera conductors and directors will leap for the original unvarnished 17th-century version, but there doesn’t seem that kind of urgency in the ballet world in going back to original texts.

But there could be artistic interest. Peter Wright, with his extraordinary background and artistic overview, was there when they first did Valses nobles et sentimentales [1947], and he will be an associate to the Foundation. You'll get all these ballerinas who may have different ideas about a piece together and have a conversation about it, rather than a confrontation. And that way you can build up the piece. It’s got to boil down to one person’s artistic judgment, but it would be a great pity if that person was too proud to look and see what’s available. Jane Pritchard gave this extraordinary lecture in which she said that Fred's Mars and Venus, which appeared at the back of the stage for an Ashley Dukes play in 1929, had had something like 500 performances because of the play's popularity so Fred had had enormous exposure really early on. And how he’d walked up to Harlem to find black dancers in Four Saints in Three Acts in 1934, and been picking untrained people off the street to get them all to do these moves. It’s important to know all of that.

We’d get as much as possible onto the internet - with films, at least telling people where to go and see the stuff, even if because of copyright problems we couldn’t put the film online.

Copyright has always been the stumbling block for TV and film. Have you found and unlocked treasures?

Obviously this is ongoing work. The British Film Institute in the last five years has got hold of and restored an awful lot. Of course there are rights problems but it is intended that the Foundation will have more of a coordinating role, identifying which archive to go to, rather than holding a central archive. That Cinderella film with Fred in it in colour was from Swedish TV, or something like that, I think.

What about YouTube? Are you going to track down all those clips?

Not at the moment, but I’m sure people in charge of the IT part of it will use every possible source.

How much will it cost to run the Foundation yearly, and how long will your founding patron contribute?

We’re fortunate to have got funding for three years [from Lindsay and Sarah Tomlinson], and executive director Christopher Nourse works part-time, but the idea is that the Foundation will fundraise itself for specific projects.

Will you be able to do enough in the first three years as core work which only needs topping off thereafter?

No, not at all. You will be supporting a wide variety of people doing ongoing projects.You’ll see where the holes are, try to coordinate everything. We have one fundraiser on and others possibly connected, raising money for specific projects that people think will be a good idea.

How does that scope compare with the Balanchine Trust and Foundation? There are 400-odd ballets they reckon can be performable. And Ashton is, what, about 50 out of 140-odd pieces large and small?

There’s a problem of scale. When some of them were made, they were for much smaller stages, different sorts of lighting. Restaging for Covent Garden shouldn't look as if somebody had got a bicycle pump and inflated it.

The end of La fille mal gardée is the end of Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier adapted in his own way

Are all choreographers as fragile as each other or are some more fragile than others?

I think Fred’s work has benefited from the fact that he was a sponge. He worked with [the choreographer of Les noces] Bronislava Nijinska in Ida Rubinstein’s company, and you see in The Wanderer (1941), those early pieces, those piles of people, very Nijinska. And knowing that enables you to have a better view on his work. His later works are in a way quoting himself - but then the end of Fille is the end of Strauss’s opera Der Rosenkavalier adapted in his way. And he was very proud of Ondine, getting all those people moving on the boat [in Act II] - Peter Brook apparently was sitting behind him saying, "I wish I’d thought of that!" So Fred was really happy with that. I think the multitude of influences on Fred means that it’s more possible to realise the ballets if you have the knowledge of them, rather than just "reproduce". Alexander [Grant] said he was once having an argument with Donald MacLeary about something and they went off to see the film eventually. But in future they should be able to start with the film, and not have the argument.

I was thinking about how some people have opined that Ashton’s work is more period, more perfumed, more indefinable, therefore more likely to be lost as an understood style - there’s been more fear expressed about the difficulty of restating his style than MacMillan or others who seem more physically robust.

I think it’s because values have changed. Ashton would want women to sell themselves in a sense, do the things that women don’t do any more. So you’ve got a double whammy there. One, you’ve got to get the performance out of the dancer, and two, you’ve got to get them to do things that aren’t fashionable any more. If you look at film of dancers in the Fifties they charm in a different way, they have a different kind of poise. I saw the performance you saw with Tamara Rojo doing Marguerite and Armand. When Sergei Polunin came on as Armand, instead of the Sylvie or Margot electric shock at seeing him, Rojo just stood there, almost with no facial expression. And afterwards that was the image that stayed with me, of her just standing there, which sent me back hunting out Dumas’s original heroine, Marie Duplessis who died at 20 or whatever riddled with disease, but had taught herself to read and write and must have become astonishing, because she had two great aristocrats at her deathbed and Liszt had her as a mistress. Those are the things that Fred was really interested in (pictured above, Rojo as Marguerite with The Royal Ballet © Bill Cooper/ROH).

I think it’s because values have changed. Ashton would want women to sell themselves in a sense, do the things that women don’t do any more. So you’ve got a double whammy there. One, you’ve got to get the performance out of the dancer, and two, you’ve got to get them to do things that aren’t fashionable any more. If you look at film of dancers in the Fifties they charm in a different way, they have a different kind of poise. I saw the performance you saw with Tamara Rojo doing Marguerite and Armand. When Sergei Polunin came on as Armand, instead of the Sylvie or Margot electric shock at seeing him, Rojo just stood there, almost with no facial expression. And afterwards that was the image that stayed with me, of her just standing there, which sent me back hunting out Dumas’s original heroine, Marie Duplessis who died at 20 or whatever riddled with disease, but had taught herself to read and write and must have become astonishing, because she had two great aristocrats at her deathbed and Liszt had her as a mistress. Those are the things that Fred was really interested in (pictured above, Rojo as Marguerite with The Royal Ballet © Bill Cooper/ROH).

Are there more arguments about Ashton style than any other ballet style? It's my observation.

I think only inasmuch as it’s been defined as “English” style. Little Freddy Ashton born in Guayaquil, Ecuador, raised in Lima, Peru, who came to England speaking with a Spanish accent, to Dover College where he was nicknamed Norsa, because he couldn’t say, "No, sir." Danced with the Queen Mother. Becomes the quintessential English person. And when I travelled with him once to New York he was described on the front page of the New York Times as New York’s favourite Englishman. But he was actually a person who’d come here from a foreign country who battled to become English again.

Is the Foundation going to become the final arbiter of “Ashton style”?

No, the Foundation is going to enable other people to realise as closely as possible what it is.

What about angles of legs?

You know that Fred didn’t like sore ears.

Sore ears! What a lovely phrase! And will the Royal Ballet be obliged to perform Ashton, even if a future artistic director doesn’t want to?

No, I think it would just be an asset for them. All the Foundation can do is oil the wheels as much as possible, to ensure maximum awareness, encourage projects where work is televised to make it available on the internet, to promote it without flooding the market, and keep standards high.

In the best way, you hope people would be ashamed about putting on something that wasn’t up to the mark

What if one of the heirs leaves their key ballets to…

A cat’s home?

...Or some very bad-taste stager, who wants to do it roughly as much as possible to get money.

Well, you can’t do anything really. At least we could get together all the information that’s available and hopefully work with them - in the best way, you hope people would be ashamed about doing something that wasn’t up to the mark. We’ve built in the possibility of the Foundation being able to own the ballets, in the longer term, should future owners perhaps want to sell them. In which case the Foundation could fundraise to buy the ballet.

So the softly-softly approach will continue.

It’s been going on all this time, for the 23 years anyway. It’s been simmering quietly and people have been getting on with it without support, actually. But now we also have the internet, and information is suddenly much easier to re-energise.

What will be the hoped-for result in 10 years?

That the Frederick Ashton Foundation would have achieved, firstly, continuity in the training of people staging the ballets, second, communication between those teaching and staging the ballets and those working on film and written archive, academic study, organising and filming of masterclasses and ballet recreations, and third, that the communication will have resulted in the highest standards in staging and performance of Frederick Ashton’s ballets.

- Contact the Trust or Foundation via Christopher Nourse

- A new all-Ashton DVD performed by the Royal Ballet, including Scénes de ballet, Les patineurs, Five Brahms Waltzes and other extracts and divertissements was released last week by Opus Arte

- The Ashton Archive website

- Find Ashton biographies by David Vaughan, Julie Kavanagh and others on Amazon

Watch the final pas de deux of Ondine, in the 2009 Royal Ballet filmed version with Miyako Yoshida and Edward Watson

Buy

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Comments

fascinating stuff, but is the

Thus it is captioned for a

Thus it is captioned for a 2009 Sotheby's sale, though likely it should be interpreted as the three being posed by Beaton on a shred or two of the Apparitions set. But yes, what IS she wearing? Can't identify her costume from ROH or V&A collections.