Music Business 2000-9: The Medium, the Message | reviews, news & interviews

Music Business 2000-9: The Medium, the Message

Music Business 2000-9: The Medium, the Message

How the music industry strangled its own golden goose

The point at which the, ah, Noughties revealed themselves to me as a decade in search of more than just a decent name arrived when Sky News' showbiz gofer phoned up to ask me to come on and blah about this exciting new band that everybody was talking about, Arctic Monkeys.

Never mind the eloquently gobby songs, the riotous sold-out gigs, the tradition of northern truculence and all the other stuff that distinguished the Monkeys (see poster right) from the rest of the indie landfill cluttering the airwaves, this wasn't a music story from Sky's point of view. It was a story about MySpace. This has been the decade when Marshal McLuhan's hoary old prophecy from the Sixties - “the medium is the message” - finally transformed music from a unique listening experience into just another kind of digital content. It wasn't what you listened to in the Noughties that seemed to matter, so much as the platform - the website, TV show, high-tech widget or whatever (the favorite shrug word of a decade stuffed for choice) - where you heard it. Or saw, streamed, bought, rented or nicked it. Or chose it as the ringtone on your mobile phone, which, lest we forget, was until recently being touted as the record industry's get-out-of-jail-free-card in a downloading game it has generally played spectacularly badly.

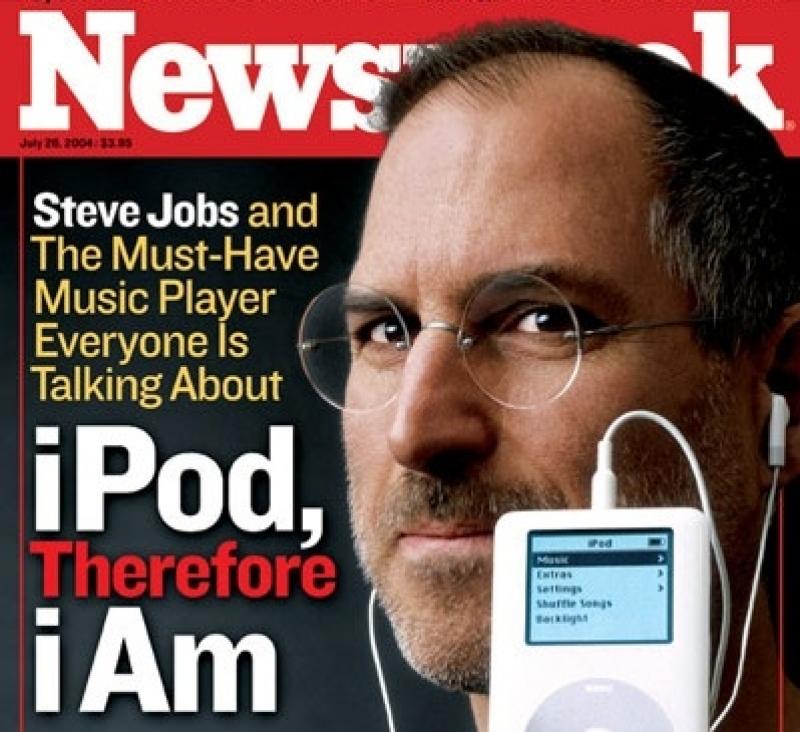

Hot new pop acts in the Noughties took a back seat to hot new media brands with names stranger than the most esoteric rock bands. In the wake of Napster and its spawn - peer-to-peer song swap sites such as Kazaa - came Spotify, YouTube, Pirate Bay and a host of other webby options. The first to capture the public imagination, and by far the most successful, was iTunes, an online music store which at a stroke enabled a computer company to boss the market in legally downloaded tracks. This came thanks to its invention of the irresistible iPod, arguably the most significant musical event of the decade. The key question among young music heads - "what's on your iPod?" - was McLuhan writ large for the 21st century: smoothly prioritising the carrier over the cargo, in line with the old Canadian soothsayer's prediction.

Hot new pop acts in the Noughties took a back seat to hot new media brands with names stranger than the most esoteric rock bands. In the wake of Napster and its spawn - peer-to-peer song swap sites such as Kazaa - came Spotify, YouTube, Pirate Bay and a host of other webby options. The first to capture the public imagination, and by far the most successful, was iTunes, an online music store which at a stroke enabled a computer company to boss the market in legally downloaded tracks. This came thanks to its invention of the irresistible iPod, arguably the most significant musical event of the decade. The key question among young music heads - "what's on your iPod?" - was McLuhan writ large for the 21st century: smoothly prioritising the carrier over the cargo, in line with the old Canadian soothsayer's prediction.

If iTunes was a boon for music fans, it was a disaster for the major labels, who had dithered over setting up a service that would have left them in control of their own product. From now on, individual songs for 79 pence would replace CD albums which not so long ago retailed for £15 a pop. Booming sales of downloaded singles may have revitalised the pop chart but they couldn't repair the gaping hole in profits created by the flight from CD, any more than the Mercury Prize could bolster support for a multi-track job-lot format which now looks terribly last century. Recorded music in the Noughties went from being a high-margin, luxury product to a cheap, low-margin commodity. No other industry has throttled its golden goose so swiftly and disastrously as the music business.

As the majors slashed their rosters ever more ruthlessly, acts were left to find their own way to an audience – and to a decent living. There's a story doing the rounds in America about an indie rock band who gave up selling CDs of their music at gigs after they discovered that it cannibalised their T-shirt sales, which were far more profitable. True or false, this tale epitomises the seismic shift in the economics of music. Live performance is now where the money lies. Concert ticket prices have rocketed accordingly – well into three figures now for the best seats for A-list acts. Merchandising can account for up to 40 per cent of the profits of a major arena tour.

The only safe conclusion so far is that Simon Cowell will always be a bigger star than any of his protégés

The net effect of all of the above on the health of music-making and career development is hard to assess. The X Factor effect has been closely analysed but the only safe conclusion so far is that Simon Cowell will always be a bigger star than any of his protégés. It's the song not the singer that scores most heavily in that market.

My general impression is that fewer durable stars have emerged since CD sales headed south in 2001. Arctic Monkeys, Kings Of Leon and, fingers crossed, Amy Winehouse are three exceptions to the rule of a decade that has buried more stars than it has nurtured. Most of the superstars entering the second decade of the 21st century were already well on their way – like Coldplay and Beyoncé - when the Noughties began. The fate of promising recent arrivals such as Lady Gaga and Lily Allen is by no means certain.

There were some notable winners in this not-exactly-brave new world. The shortage of 21st-century acts capable of filling giant stadia like London's 18,000-capacity O2 opened the door for a comeback bonanza. Everybody, even the notoriously quarrelsome Spandau Ballet, Blur and The Police, buried ancient scores and cashed in on their most lucrative tours ever. The elderly legends with reputations too grand and longstanding to be affected one way or the other by media innovations did well too. Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young and Tom Waits had unexpectedly successful decades as they entered their sixties or even seventies. The 76-year-old Cohen's beauty from 1984, “Hallelujah”, became a surprise smash with the TV talent crowd on both sides of the Atlantic, and emerged as the decade's most popular tune.

The really smart guys meanwhile surfed the wave, subverting new technology, and enhanced connectivity with fans for their own ends. Radiohead launched what was in effect a comeback with their 2007 album In Rainbows, whose bold use of their website as a record shop without a cash register - just an honesty box for downloaders - re-established them as the world's hottest rock band. In Rainbows also earned them more than any of their previous albums with EMI.

Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlett spotted which way the wind was blowing too. Their cartoon band Gorillaz was a musically sophisticated joke that employed all the techniques of new media to sell more music in a brief spell in the Noughties than Albarn's old band Blur had throughout the whole of 1990s. So roll on the Teenies, or whatever the place in the calendar where we now live is to be called. For hardcore music fans and X Factorites alike these are, to put it mildly, interesting times.

Watch Gorillaz's "Clint Eastwood":

{youtube width="400"}ue3M_kxb85Y{/youtube}

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Comments

...