'You want to cry from loving to do it so much' - Lynn Seymour 1939-2023 | reviews, news & interviews

'You want to cry from loving to do it so much' - Lynn Seymour 1939-2023

'You want to cry from loving to do it so much' - Lynn Seymour 1939-2023

Remembering the unique ballerina who injected me with her poison

As a critic, I’ve rarely felt compelled to mourn publicly about an artist. Mourning goes somewhere beyond the usual sense of loss and gratitude when someone's death has been announced. But it's the only word when the departed is one of the very few individuals - or their songs or books or pictures - who get in your bloodstream, who get into your optic nerves or your inner ear, who magnify and sharpen your experience of being alive.

Lynn Seymour’s death last Wednesday undammed an outpouring of truly wrenching sadness from those whom this extraordinary ballerina injected with her poison - as the choreographer Frederick Ashton memorably said about his enslavement to Anna Pavlova. The Royal Ballet issued beautiful words about their prodigal daughter whose career was shadowed by her popular reputation as the rebel against the system, the ballerina who stayed out in the cold.

Ballerinas wore two-pieces and hats in public, smiled, and said little. Pure Fifties. But Seymour was pure Sixties, and then some

Some of it was the downside of being a magician. She so mesmerisingly evoked the intriguing human beings offered by choreographers in new stories specifically for her dramatic talents – the original rebellious Juliet in Kenneth MacMillan's now classic Romeo and Juliet, a bored housewife in A Month in the Country, a sex-obsessed groupie in Mayerling, a pioneering free spirit in Five Brahms Waltzes - that she got categorised as all of those things herself.

Besides, there were just so many good girls about in ballet, or they kept their bad behaviour well concealed. The Covent Garden PR machine worked overtime on Margot Fonteyn’s very impure private life, and on the multiple marriages and gay affairs of Seymour’s peers. Basically, ballerinas wore two-pieces and hats in public, smiled, and said little. Pure Fifties.

But Seymour was pure Sixties, and then some. She smoked cheroots and drank beer, had big sooty eye make-up and bubble curls, married quite often, shacked up quite often, was funny and outspoken, and critics used words like “voluptuous” and “womanly” about her, to distinguish her physique from the emerging stick insect ideal. Her first husband, the dancer and photographer Colin Jones, took a wonderful picture of her and her mate Rudolf Nureyev in The Crown on the North End Road in 1965 (below).

That the bad girl imagery was a complete betrayal of Seymour’s actual qualities as an artist only came to me too late to stop adding to the damage. It’s my shame that when I first went to interview her when very new in my job I fell into that terrible trope. She rightly slapped me down for it. But the interview continued, and I hope she saw that what I was trying to get to, cumbersomely, was that it was her ability to use ballet dancing to express the public’s own failings and sufferings - or mine, if one’s honest - that made her an essential interpreter of the art, rather than nice-to-have like most.

That the bad girl imagery was a complete betrayal of Seymour’s actual qualities as an artist only came to me too late to stop adding to the damage. It’s my shame that when I first went to interview her when very new in my job I fell into that terrible trope. She rightly slapped me down for it. But the interview continued, and I hope she saw that what I was trying to get to, cumbersomely, was that it was her ability to use ballet dancing to express the public’s own failings and sufferings - or mine, if one’s honest - that made her an essential interpreter of the art, rather than nice-to-have like most.

Her thin skin wasn’t a childhood trauma or victim complex that needed fixing. Thin skin was intrinsic to Seymour’s approach to dancing

The point I finally realised as I wrote her obituary last week was that her thin skin was essential, that it wasn’t a childhood trauma or victim complex that needed fixing. Thin skin was intrinsic to Seymour’s entire focus and approach to dancing, because evidently she had always sensed that only by keeping her receptors unguarded could she explore possibilities.

Her remarkable articulacy and insights are on view in her childhood diary, extracted in Richard Austin’s 1980 biography of her. When the shy teenager from the small Canadian prairie town of Wainwright (population 6,000) arrived at the Royal Ballet School, she cried into her diary, “I am an earth-bound worm.” She knew exactly what the problem was - earth-boundness.

And this kid could express verbally better than any critic or dancer or choreographer I’ve ever read the exultancy of extreme dancing: “She gave us some terrific dance steps – the kind that the music and movement make you want to do them so badly. Oh golly, how I plunged into them and really felt I was dancing. The sheer effort and tautness you put into it made you want to cry from loving to do it so much.”

It's not a great surprise that seeing the film The Red Shoes as a child in Canada was her moment of lifetime commitment. That dangerous abandon was exactly what her performing of Juliet (pictured right by Roy Round) or Giselle or Tatiana in Onegin showed. Only the most naturally intuitive and courageous dancer would know that, so young. And I think only the very greatest would see how that huge thrill had to be knocked back and kneaded and refined in the most exacting training.

It's not a great surprise that seeing the film The Red Shoes as a child in Canada was her moment of lifetime commitment. That dangerous abandon was exactly what her performing of Juliet (pictured right by Roy Round) or Giselle or Tatiana in Onegin showed. Only the most naturally intuitive and courageous dancer would know that, so young. And I think only the very greatest would see how that huge thrill had to be knocked back and kneaded and refined in the most exacting training.

Seymour felt rather trapped in the "greatest dramatic dancer of the era" tag bestowed on her by Ninette de Valois, the Royal Ballet founder, and believed she only started dancing classical roles decently in her mid-thirties, after Nureyev introduced her to the great New York teacher Stanley Williams.

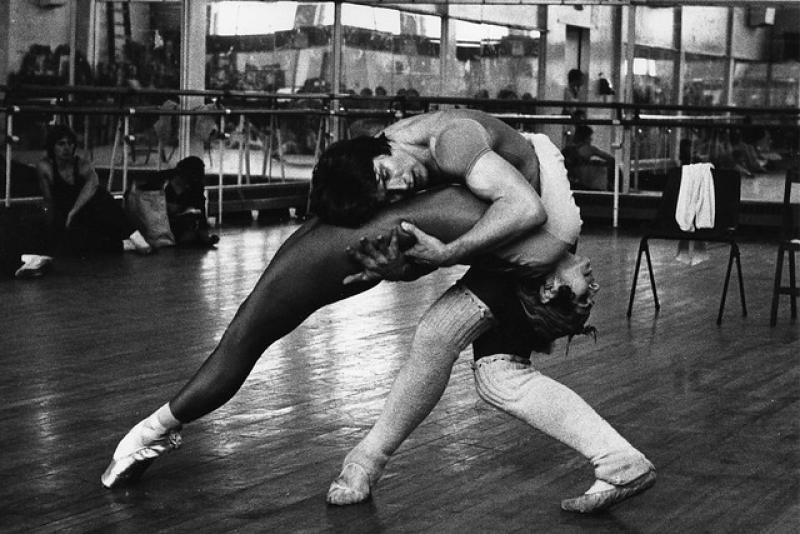

Watching the scant videos of Lynn Seymour now on YouTube, I see how dreadfully the rebel image obscured understanding what kind of performing genius she was. Her Juliet, Mary Vetsera and Giselle certainly let every vein, and the late roles I saw her in, Natalia Petrovna, Tatiana and Anastasia, let mine. But her dazzling dancing with Nureyev in The Sleeping Beauty Act 3 in 1977 at Covent Garden shows her succumbing to the deliciousness of feasting on classical steps, illustrating what she had taken from mature study with Williams. A rehearsal tape of her simply marking out the early Romantic classic La Sylphide with Peter Schaufuss and the Chicago Ballet is breathtaking, because even in unselfconscious rehearsal mode, Seymour’s legs could not stop making exquisitely soft shapes, her arms and hands could not stop being deliquescent, rounding out movement phrases that welled up from deep down inside her - she was so rich in the body and so light on her feet.

Here she is in the final minutes of A Month in the Country, a role Ashton created for her at the Royal Ballet, as Natalia Petrovna, whose sudden passion for her children's tutor (Anthony Dowell) is exposed and must end.

Seymour said that none of this was her unique gift, most of it might be passed on to dancers and to art-makers – the choreographers, the artistic directors, the coaches and schools – if only the Royal Ballet “establishment” recognised that such learning was desirable, and would build training and programme development around those expressive aims.

She also worried about the content. In 2000, alarmed by the rapid disappearance of decades-worth of British ballet and contemporary dance artworks, she met me again to call for the establishing of a balletic version of the National Trust, to define, preserve and develop a core repertoire of what made the “English” school different from others (say, the French, American or Russian schools).

This would be a resource guiding staging and teaching practices – a foundation supervising key creations by Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan, Antony Tudor and other formative British dancemakers, and vital acquisitions by Nijinska and Fokine. Having written several times about the laissez-faire attitude abroad among the disparate heirs to these ballets, and about the disappearing chances to mine original performers of historic ballets of their precious knowledge, I thought Seymour’s idea sane, well-considered and eminently applicable.

I think the nation needs to feel it has a sense of ownership about English ballet, the same sense of ownership as it feels about Shakespeare

“I think the nation needs to feel it has a sense of ownership about English ballet,” she said, “the same sense of ownership about Ashton as it feels about Shakespeare. Not every work, but the key works. And these must become the base and cornerstones for future dancers and choreographers to study with infinite care, to further their artistic understanding. It involves ownership - just as you would buy a Tintoretto or a Bacon for the National Gallery. This core of essential ballets needs to be defined so that if there is some lousy government or even some lousy artistic policy at the Royal Ballet, it’ll be protected.”

One might call this prophetic vision, since she was speaking just before the disastrous (mercifully brief) Royal Ballet directorship of Ross Stretton which threatened to break up the Ashton and MacMillan legacy. And it’s become an even more pressing concern over the last 20 years as the rapid turnover of ballets is rated, as an artistic process, more highly than any wider evaluation of what’s in and what’s out. In addition, today more than ever, “if there is some lousy government” is no longer a theoretical possibility when it comes to the lyric arts.

Take away all that hindsight, and Seymour’s perceptiveness and constructiveness shine out - qualities common to many of the things she said, which should be stuck on fridges everywhere.

“I never thought about the audience. The important thing was doing what the choreographer wanted, and doing it well.”

"Performing is a bullfight. Everyone is waiting for a bucket of blood. I think you should let every vein."

“To be a ballet dancer you have to be first a craftsperson. Your job is to do the magic, not experience it.”

And back to that teenage diarist once more:

“The sheer effort and tautness you put into it made you want to cry from loving to do it so much.”

Lynn Seymour, 8 March 1939-7 March 2023

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Comments

The best thing I've read

I agree with you. With all my

This is a touching -- and

Seymour's silent scream of

What a wonderful dancer

I saw her first performance

She was on tour with ENB in