Don Quixote, Bolshoi Ballet, Royal Opera House | reviews, news & interviews

Don Quixote, Bolshoi Ballet, Royal Opera House

Don Quixote, Bolshoi Ballet, Royal Opera House

Choreography Javier de Frutos reviews extraordinary dancing by the golden pair

There is a moment when you see dancers at their absolute peak that notches a bit of history in your memory - you never forget when you see it happen. In my area of contemporary choreography you can’t measure it in those terms but you can with classical ballet, and a Don Quixote performance like I saw at the Bolshoi last night sets the bar. This level of performance is Olympic-sized, it erases everything else you have seen.

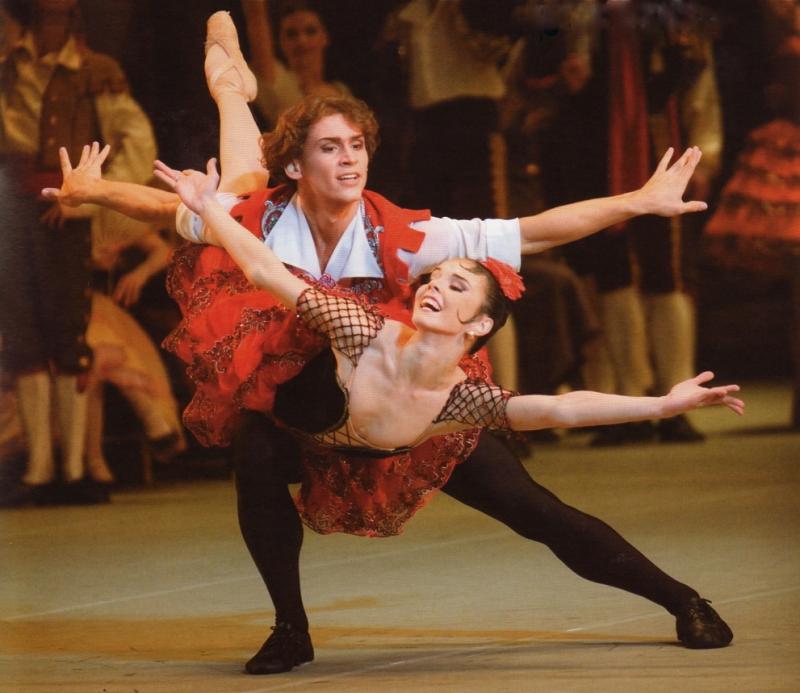

Of course it’s the pair of them that this ballet is about, Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev, the two of them uniting their fabulous youth and abilities in a click with the moment. You had a sense that they knew they could do just whatever the hell they wanted, when technique is just an instrument and nothing more. Osipova is extraordinary in terms of speed, but it’s him, it’s Vasiliev who is even more fascinating.

I went to YouTube beforehand and found videos of him even younger, and you go wow! of course, but I was in trepidation that this would just be bravado. But actually seeing him you run out of things to say; he seems to add new steps to the lexicon, he seems so embedded in his body that it’s as if he just thought about those steps now. So it isn’t gymnastic any more - he’s actually dancing the tricks.

I had no sense whatever that this is a very long-familiar role to him. The comparison with Baryshnikov is compelling. I always like compact dancers, and he has a very low centre of gravity, which is a secret of how fast he goes up and comes down. (This is not dissimilar to a contemporary dancer.) But he is also a most intelligent dancer, and not even 22 - it would be fascinating if like Baryshnikov he one day found a latterday Twyla to help him go on being as intelligent in other forms of dance as he was in Don Q last night.

Vasiliev and Osipova dance the coda to the pas de deux in Don Quixote in Novosibirsk 2008:

There is a daring between the two of them that is truly unusual and the chemistry is obvious. Osipova has incredible attack (I could not believe she had just done Giselle) - it’s one of the few times with a classical ballerina that I have realised I was sometimes unaware that she was on pointe. The pointe seems to be a complete extension of her movement, so you just assume she is so giddy and euphoric that she flies. This is technical mastery of an astonishing degree. And yet in the Dryads scene, Osipova became Dulcinea technically. Because Dulcinea is a heroine of the ubiquitous white ballet, Osipova transformed her style and muscle movement so completely that I had to double-check it was her. You were left gasping about how quickly she became a “white act” ballerina. That is one of the magical things that the 19th-century dramatic ballets do, offer this kind of technical and atmospheric challenge.

I also particularly liked two of the secondary soloists. The streetdancer, Anastasia Yatsenko, was terrific - just completely not trying to state where her position was in the ranking, not trying to outdance anybody, but just doing her thing with the daggers on the floor in a very abandoned style, and you half believed that woman on pointe is a streetdancer. And I thought Espada, Vitaly Biktimirov, seemed to have researched the toreador stuff really properly. I cannot remember such a great amount of cape choreography, nicely done. He didn’t look fake, there was a real sense of joy from him and from the whole company.

The fact that the story is so slight is an advantage, because the night becomes a stylish competition between characters, which transfers a lot of spirit from the technical level up into an extraordinary theatricality. I love clichés in theatre, in ballet as much as anything and when I see ballets like this, I go, god, if it wasn’t for this kind of music and this kind of construction there would have been no MacMillan and no Matthew Bourne.

The fact that the story is so slight is an advantage, because the night becomes a stylish competition between characters, which transfers a lot of spirit from the technical level up into an extraordinary theatricality. I love clichés in theatre, in ballet as much as anything and when I see ballets like this, I go, god, if it wasn’t for this kind of music and this kind of construction there would have been no MacMillan and no Matthew Bourne.

The lovely thing is the naivety of the exotica, which you have to judge in its time and place. In the middle of the 19th century the audience were people who would never travel out of Russia, and somebody obviously said, let’s bring a little bit of Spain in. Nobody was there saying, ooh this isn’t Spanish enough. Actually they maybe thought Minkus had been to Spain, and brought these melodies and rhythms back from there like a merchant with spices.

The truth is that what they have is really not that far from the real sense of Spain, partly because the Russians understand so well that the exotic is what sells this ballet. They seem to do this ballet now less “Russian” and more freely in a Continental character. They’ve kept that tradition of the “exotic vision” that Petipa was fulfilling, and kept it deliciously. The picture of Spain given by the sets is all over the place - geographically we start in a square in Barcelona and then we’re inside a palace in Seville or somewhere, but the transference of the classical vocabulary to Sevillana and Jotas has far more detail and more of an attempt at authenticity than I remember before.

And there are fantastic speciality numbers. Obviously the music does not correspond to original regional msic - you can’t actually put sevillanas or bolero steps to the music, so therefore what you get is an attempt to fit one thing to another in a sort of cocktail, a fusion of tastes, and you had to suspend disbelief. Don Q is not about Cervantes’ Don Quixote, it’s just a big, clever marketing ploy.

I wonder what the briefing was in Alexei Fadeyechev’s revival. They haven’t got rid of any of the clichés that we loved when we were kids, it’s just slightly more “real”, freer in delivery. I didn’t want a single change to those painted backdrops you don’t get in theatre any more where technique have changed to photographic ones. The Dryads Scene is presented in an enchanted forest made of handpainted gauzes in layers, and slightly wrinkly in places - and you go, Wow! how lovely! It takes you back to the memory of going to the ballet when you were a child, when just seeing the cloths move from one side to another to make a new scene felt like magic.

When you see it now, four acts and a hell of a lot of mime, it’s easy to forget that this was a novel entertainment when it was made, on many levels. Petipa all that time back in 1869 was using a new score by Minkus which nobody had heard, and he had a plot to deliver that wasn’t much to do with the familiar Don Quixote story. It’s a strange and quite informative feeling for me right now because with my ballet with Ivan Putrov and the Pet Shop Boys next spring I am doing narrative stuff with a real story that no one knows the ending to, and new music, and it’s a full three-act ballet. The distraction of everything being “new” is going to be something to counter.

I do go to a great deal of ballet - it’s for nostalgic reasons, but I have always felt it was important to know your history. Balanchine is the intellectual link between Petipa and contemporary choreography. As a choreographer I found myself very interested in the Dryads scene: in many Don Q productions you dread the Dryads, but for this version it has been quite seriously edited here and there. You get this controversial feeling as when a museum presents a famous painting that has been restored, and you wonder if it really was that blue or that red. But I found myself captivated by the corps de ballet, because the ensemble wasn’t as symmetrical as I remember it in other Don Qs - it was group-oriented, and each group seemed to have a level of attention paid to its particular detailing, and in terms of the composition too.

We keep talking about narrative in ballet, but all choreography has a lot to do with composition and the abstract act of dancing. The grand pas de deux is a completely plotless display of physicality, with the fouettés and marvellous manèges you hope for. And then we get the intelligence of the dancers finding liberation within the set variations - like Vasiliev seeing how he can observe and then break the rules, and Osipova firing off the fastest 32 fouettés I have ever seen, just breathtaking.

We keep talking about narrative in ballet, but all choreography has a lot to do with composition and the abstract act of dancing. The grand pas de deux is a completely plotless display of physicality, with the fouettés and marvellous manèges you hope for. And then we get the intelligence of the dancers finding liberation within the set variations - like Vasiliev seeing how he can observe and then break the rules, and Osipova firing off the fastest 32 fouettés I have ever seen, just breathtaking.

And in the Dryads the formation of dancers in classical work is something that you can construct and deconstruct forever. It doesn’t matter what Merce Cunningham said about his work, there were many deep debts to classical dancing there, because of the logic and symmetry in his choreography that comes from corps de ballet right the way back to the 17th century.

- Javier de Frutos (pictured left) will be creating a ballet with Ivan Putrov and the Pet Shop Boys at Sadler’s Wells in March next year

- The Bolshoi Ballet perform Don Quixote today (mat & eve) and tomorrow. The Bolshoi Opera performs Eugene Onegin next week

- Read theartsdesk reviews of the Bolshoi's Spartacus - Coppelia - Serenade/Giselle - Le Corsaire & 'Russian' Triple Bill

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Comments

...