'You’re Jewish With a name like Neumann, you have to be' | reviews, news & interviews

'You’re Jewish. With a name like Neumann, you have to be'

'You’re Jewish. With a name like Neumann, you have to be'

Introducing 'When Time Stopped', a powerful new investigative memoir about the Holocaust in Czechoslovakia

It was during my first week at Tufts University in America, when I was 17, that I was told by a stranger that I was Jewish. As I left one of the orientation talks, I was approached by a slight young man with short brown hair and intense eyes. He spoke to me in Spanish and introduced himself as Elliot from Mexico.

“I was told we should meet,” he said, beaming. “Because we’re both good-looking, Latin American, and Jewish.”

I was baffled. I’ve never been good at witty comebacks, but I was thrilled to manage: “I’m sorry, you’re mistaken. I’m not Jewish, and you’re not good-looking.”

“You need glasses,” Elliot responded cheerfully, undeterred. “But you’re Latin and, of course, you’re Jewish. With a name like Neumann, you have to be.”

“You’re wrong.” I replied. “I was raised Catholic.”

“Where is your father from?”

“He’s Venezuelan, but he was born in Prague,” I answered.

“Call yourself whatever you want, but you must be Jewish.”

This marked the first time I’d heard the word “Jewish” uttered by anyone in reference to me, my father or, for that matter, anyone else I knew. I’d grown up in 1970s and ‘80s Caracas. The Venezuela of those years was filled with potential and optimism. My father, already 50 by the time I came along, had emigrated from Czechoslovakia to Venezuela in 1949. He had built an industrial conglomerate and had married my Venezuela-born mother, 20 years his junior. My mother’s family had been Catholic for generations, but she was never particularly religious. That didn’t stop me from being placed in an Ursuline-run school and, aged eight, briefly toying with the idea of becoming a nun. The bitter taste of communion wine cured me of that notion. As a child it was my father who would take me on a handful of Sunday afternoons to a mass in a simple chapel attached to an old people’s home down the road from our house. He once explained that he preferred it to more traditional services because there was no sermon.

I’d never thought about my religious identity until that day at Tufts. Why had the subject of religion rarely been discussed at home? Was my father a Jew? Was I?

In those few times I went to church with my father in Venezuela, something struck me as odd. As the congregation recited prayers in unison, my ever-preoccupied father remained silent. It was only when it was time for the “Our Father” that his mouth moved. I listened carefully and noticed that he was whispering the prayer in a foreign language, Czech. (Pictured below: Ariana Neumann © Serena Bolton)

I know now that he learned the prayer in Czech as part of an elaborate and daring ploy to survive. But as a child, the fact that my paternal family had been Jewish was kept from me. Perhaps my father felt that it was something that I didn’t need to know. Perhaps it was an attempt to protect me. Something else no one ever mentioned - a truth I discovered only recently - is that 25 of my family members were killed for the simple reason that they were Jews.

I know now that he learned the prayer in Czech as part of an elaborate and daring ploy to survive. But as a child, the fact that my paternal family had been Jewish was kept from me. Perhaps my father felt that it was something that I didn’t need to know. Perhaps it was an attempt to protect me. Something else no one ever mentioned - a truth I discovered only recently - is that 25 of my family members were killed for the simple reason that they were Jews.

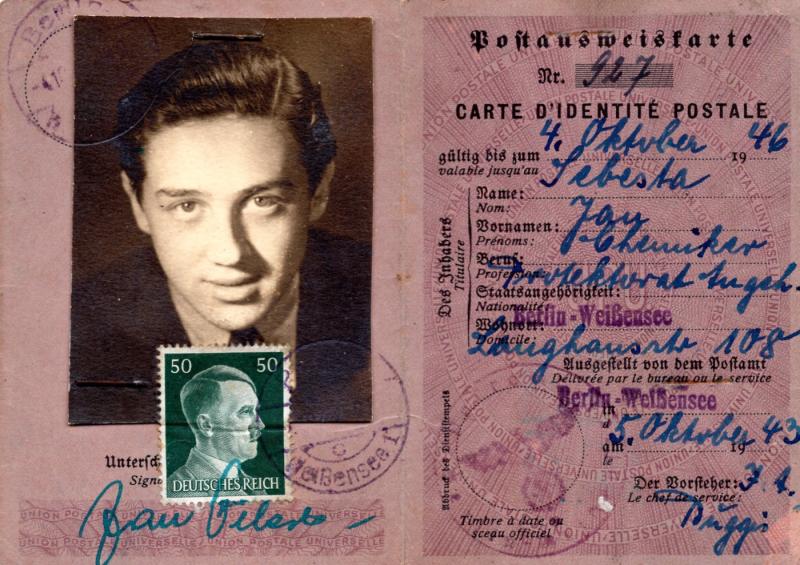

When my father died in 2001, he left me a box filled with papers from World War Two that helped me piece together his “secrets”. It took me years, but I uncovered an extraordinary story centred on my father’s audacious decision to hide in plain sight in Berlin, pretending not to be Jewish and in constant mortal danger. Only by uncovering that story and the fact that my father had lost so many of his loved ones did I understand why he was unable to speak fully about his life before and during the war. I see now that the bequest of that box was his way of sharing his experiences, of allowing me a glimpse of who he was before I came into his life.

My parents were together for 18 years, but my father kept the bulk of these secrets from my mother too. She knew a little more than I did, but even her knowledge was limited. When I asked her recently how aware she’d been that they were keeping this history from me, she said it had never been an active choice. They weren’t outright lying, just not disclosing certain things. There is a fine and blurred line between the two.

Family secrets aren’t categorical lies; often, they’re just things kept hidden: experiences that remain unspoken, stories that for many reasons remain untold.

All families have secrets. Often, we deem them insignificant. They simply don’t add to the image we have of ourselves or that we wish to project to others, so we push them to a corner of our consciousness. But sometimes events are too painful to re-live and are buried so deep that the keeper of secrets loses awareness of what he or she is withholding. This was probably true of my father. I sometimes feel cheated that he didn’t pass on his inheritance. But perhaps it’s not surprising that, having lost so many of his family because of their religion, he found himself unable to introduce his children to it.

As I look back, I realise that the encumbrance of my father’s past, the unidentifiable but crushing weight of his secrets, was always there. I often wonder if the burden of suppressing a terrible truth exceeds even the weight of the truth itself.

Recently, I chatted with a therapist friend who told me the story of her father, an older man who’d always felt that a secret had been kept from him - that his father wasn’t actually his biological father. He tried to move on from his suspicion but the burden of the untold was unavoidable. For a million reasons he felt that he couldn’t ask, and yet the desire for the truth remained. He’d hoped that once his mother died his need to know would be buried with her. But he’d been wrong. That need remained. For his 82nd birthday last year my friend gave her father a genetic test kit that confirmed what he’d always suspected - he had, in fact, been the product of an illicit love affair. The news provided relief for him, confirming as it did what he had, on some level, known for a long time. At 82 he is getting used to his new reality, incorporating it into his identity and developing a relationship with his half-brother and his new family.

Recently, I chatted with a therapist friend who told me the story of her father, an older man who’d always felt that a secret had been kept from him - that his father wasn’t actually his biological father. He tried to move on from his suspicion but the burden of the untold was unavoidable. For a million reasons he felt that he couldn’t ask, and yet the desire for the truth remained. He’d hoped that once his mother died his need to know would be buried with her. But he’d been wrong. That need remained. For his 82nd birthday last year my friend gave her father a genetic test kit that confirmed what he’d always suspected - he had, in fact, been the product of an illicit love affair. The news provided relief for him, confirming as it did what he had, on some level, known for a long time. At 82 he is getting used to his new reality, incorporating it into his identity and developing a relationship with his half-brother and his new family.

The more I speak to people who grew up around secrets, the more I realise that the heft of secrets shape us. Our identity is formed not just from the stories we’re told but those we aren’t. The irony is that secrets are often withheld to give us the freedom to choose who we want to be.

When it comes to our parents, all of us choose to perceive limited facets of who they are - and even those are drawn from what they allow us to see. I do it with my own children. I act as if I’m more in control than I feel. I tell them certain stories about my childhood and omit others, especially if those stories are about pushing boundaries or taking unnecessary risks. When my kids were younger I omitted the tales that might diminish their image of me as their ever-reliable mother. I did it not out of duplicity but, rather, a need to protect. I’ve never kept a secret of the magnitude of my father’s, but I often wonder if what I deem unnecessary for my children to know might one day be important to them. Perhaps because of my father’s story I try to pass on as much information as I can about their heritage - the one I grew up with as well as the one I’ve just unveiled. I want my kids to have a sense of the worlds in which their own histories started, even though they’ll never inhabit them. I want them to know the stories of those who came before. We craft our future from the light we find between the shadows of our past.

If in gazing at those who come before us, we don’t peer carefully behind the facades and beneath the silences, we risk leaving secrets shrouded and essential stories untold. The timing doesn’t always work as it should; sometimes it is left to subsequent generations to uncover the important stories. But that makes the work of uncovering them no less crucial.

- When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains by Ariana Neumann is published by Scribner

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment