The Story of Scottish Art, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

The Story of Scottish Art, BBC Four

The Story of Scottish Art, BBC Four

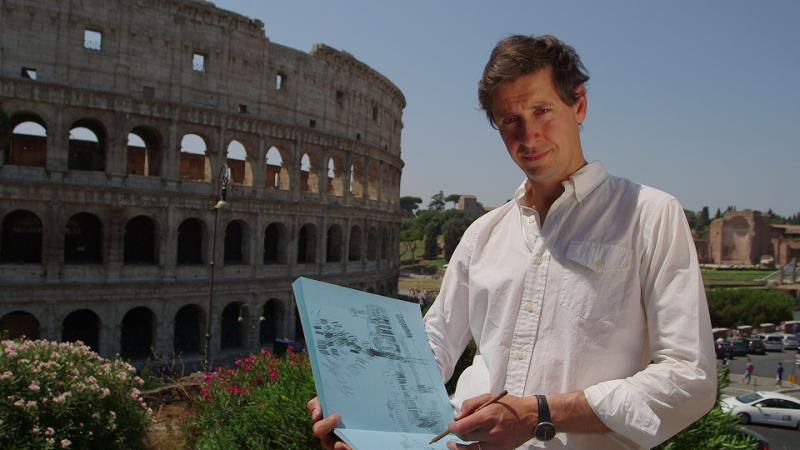

Artist Lachlan Goudie's excellent survey of his country's art takes us to Rome

“Finding the Light”, the second episode of this four-part series, took us to the period when Scottish intellectuals led the world in innovative and revolutionary thinking, Edinburgh’s neo-classical architecture in the leafy streets of the New Town made for new standards of civic architecture, and Scottish education could be of the highest quality.

The exceptionally enthusiastic narrator is the Scottish representational artist Lachlan Goudie, who rather disarmingly sketches as he goes, particularly in the city and galleries of Rome where Scots of the Enlightenment went for even further enlightenment. Goudie’s eloquent script made sense of a huge subject, taking in everything from the philosophical innovations of that superb pragmatist David Hume, the novels of Walter Scott, and the infatuation of the young Victoria with the Highlands, by concentrating on half a dozen artists who span a century. He’s passionately engaged with the subject and an eminently persuasive guide, although some assertions – that artists are by nature sensitive people, for one – are certainly provocative and ripe to be challenged.

The excitement of Rome must have been, Goudie speculates, hallucinogenic

In a throwaway line, Goudie suggested that the catalyst for the liberation of Scottish thought and the impetus for the country’s remarkable intellectual achievements may have been the Act of Union 1707 – let us hope no SNP politician notices. John Knox’s Presbyterian fervour had stifled Renaissance yearnings: his faith had been in words, not pictures, we were told. Darkness and restraint had been the order of the day, but now the light flooded in, built on the ashes of the Reformation.

We started with the marvellous portrait painter, Allan Ramsay (1713-1784), who was to take London by storm, becoming indeed Painter in Ordinary to George III. Earlier, at 23, he had migrated to Rome for a couple of years and would remain a frequent visitor for the rest of his life. He copied and drew from Roman antiquities and Renaissance masterpieces, walked the Roman campagna, and found the ruined remains of the poet Horace’s farm. The excitement of Rome must have been, Goudie speculates, hallucinogenic. He was a meticulous draughtsman but also learnt to prepare his canvases with an underpainting of blood-red, adding unexpected depth (Lachlan Goudie with Ramsay's Anne Cockburn, Lady Inglis, at the National Gallery of Scotland, pictured below.)

We saw enough to appreciate the extraordinarily subtle emotional force that underlies his superbly evocative portraits. There was one of David Hume, charmingly prosperous, slightly double-chinned, and resplendent in a red jacket trimmed with gold; also images of the artist’s two wives, a marvellously tender drawing of a son who died in infancy, frank self-portraits, and more. Art, in keeping with Enlightenment philosophy and pragmatism, Ramsay said, should be grounded in what was in front of you: it is Ramsay’s observational skills and empathy that make his portraits so vividly compelling, and the power of this programme resided in its ability to not just tell us this, but to show us.

We saw enough to appreciate the extraordinarily subtle emotional force that underlies his superbly evocative portraits. There was one of David Hume, charmingly prosperous, slightly double-chinned, and resplendent in a red jacket trimmed with gold; also images of the artist’s two wives, a marvellously tender drawing of a son who died in infancy, frank self-portraits, and more. Art, in keeping with Enlightenment philosophy and pragmatism, Ramsay said, should be grounded in what was in front of you: it is Ramsay’s observational skills and empathy that make his portraits so vividly compelling, and the power of this programme resided in its ability to not just tell us this, but to show us.

There were other points of view, too: much of the upper-class Gavin Hamilton’s (1723-1798) work is actually still in Rome, including the surprising decoration of the Borghese Palace’s ceiling. Hamilton painted elaborate Roman mythologies, sumptuous and opulent, in keeping with his interests, and loved Rome so much he spent his life there, painting a great deal, and also – like so many expat artists, including Ramsay to an extent – dealing in antiquities and art, which helps explain the fine collections made by the milordi on their Grand Tours.

And so on to the most ubiquitous Scot of all, the architect Robert Adam, whose neo-classical buildings are influential worldwide. He signed his letters to Ramsay “Bob the Roman”, while his nickname for the painter as they drew side by side in the Colosseum was “Old Mumpy”. Adam’s Roman sketchbooks are held in the Adam Research Library in that extraordinarily idiosyncratic cabinet of curiosities in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the Soane Museum, and Goudie obligingly turned the pages for us. We visited Syon House too, where the glories are the amazing interiors, restrained and opulent simultaneously.

Goudie, however, persuaded us that his great and somewhat ignored masterpiece is the tomb for David Hume (1778) in Edinburgh’s Calton Hill cemetery (depicted above). It is a cylindrical tower, ceiling open to the sky and thus the stars: it is an amazing contrast to the Sir Walter Scott Monument visible on the skyline, in that edifice’s obeisance to over-the-top romanticism. We saw Scott, with his dogs, in Henry Raeburn’s portrait, and that artist is responsible too for the most iconic Scottish portrait of all, The Macnab, in full flow with bonnet and kilt – a dissolute, drunken, spendthrift womaniser (32 children at a conservative count, but how many mothers were not revealed): what an emblem for the nation! On from there to peasant scenes from David Wilkie, the sufferings of the poor, and John Knox portrayed as a fiery preacher.

Goudie, however, persuaded us that his great and somewhat ignored masterpiece is the tomb for David Hume (1778) in Edinburgh’s Calton Hill cemetery (depicted above). It is a cylindrical tower, ceiling open to the sky and thus the stars: it is an amazing contrast to the Sir Walter Scott Monument visible on the skyline, in that edifice’s obeisance to over-the-top romanticism. We saw Scott, with his dogs, in Henry Raeburn’s portrait, and that artist is responsible too for the most iconic Scottish portrait of all, The Macnab, in full flow with bonnet and kilt – a dissolute, drunken, spendthrift womaniser (32 children at a conservative count, but how many mothers were not revealed): what an emblem for the nation! On from there to peasant scenes from David Wilkie, the sufferings of the poor, and John Knox portrayed as a fiery preacher.

Then came the Clearances, described as prioritising the rich man’s sport over poor men’s lives. The archetypal image is The Monarch of the Glen by Landseer (Queen Victoria’s favourite artist). There is an understated irony in the journey from Ramsay’s brilliantly understated portraits to a stag reigning over his kingdom; the animal’s ultimate fate was presumably to be shot for sport. The whole programme was a gorgeous whistle-stop tour and we ended in the vast vistas of Scottish landscape paintings by Horatio McCullough. Next week we leave Romanticism in favour of “Rebel Hearts”, notably the Glasgow Boys. It’s proving a compelling journey.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Does for Scottish Art what

Discovered Allan Ramsay

Discovered Allan Ramsay portrait of Fhttplora MacDonald ://www.wmgallery.com/masters