Album: Brian Eno - Foreverandevernomore | reviews, news & interviews

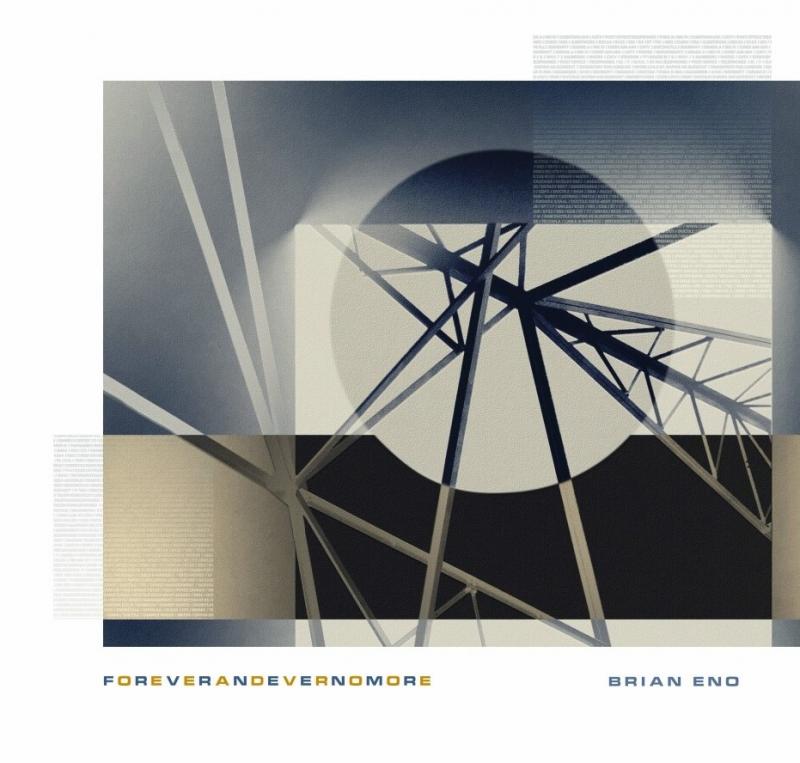

Album: Brian Eno - Foreverandevernomore

Album: Brian Eno - Foreverandevernomore

Eno's ambient approach to the climate emergency

“Our only hope of saving our planet is if we begin to have different feelings about it,” Brian Eno writes in introduction to his new album in five years, Foreverandevernomore (the first featuring his own vocals since 2005’s Another Day on Earth).

“Perhaps if we became re-enchanted by the amazing improbability of life; perhaps if we suffered regret and even shame at what we’ve already lost; perhaps if we felt exhilarated by the challenges we face and what might yet become possible.”

Not, he adds, that this is a preachy album of propaganda songs. And it isn’t. Its mood music. It intimates, not instructs. Album opener “Who Gives a Thought” is stacked with the sonic tectonics of whichever algorithms and electronic synth pads Eno is experimenting with at the moment, while his baritone voice intones and settles over a murmuration of bleeps and wooshes.

“We Let it In” features an undertow of the kind of sublingual, guttural breathing you may get on slasher-movie soundtracks right before a killing, set against vocal images of “the sun running gay with open arms though fields”, giving you the feeling something bad’s going to happen, and soon. “Icarus or Bleriot” features more of the album’s out-of-this-world electronics – Eno still finds sounds in the ether that none of us have heard before now – and its conflagration of the falling boy of Greek myth and the first person to fly the English Channel points to the civilisational fall from grace into global warming and its hot, fevered breath in our faces.

His brother Roger features on the album – their 2020 collaboration, Mixing Colours, was excellent – as well as guitarist Leo Abrahams, electronica artist Jon Hopkins, software designer and computer musician Peter Chilvers, Irish singer Clodagh Simonds, and family members Cecily and Darla Eno.

The album’s many layers of electronics and synthesised sounds, caught in their languid, ever-shifting state of suspended animation, are the album’s signature, and while Eno’s treated vocals have a warm and attractive, if sometimes formal, texture, there are contrasting female vocal contributions, too, on the likes of the glacial, wreath-like “I’m Hardly Me”, set against bird-like electronic chirps and shifting sonic backdrops.

If you feel like lying back and drifting off to the land of “forever and ever no more”, do so to the eight-minute album closer, “Making Gardens out of Silence” which begins with textures of sound that feel so delicious you just want to drape them about your skin like a pelt.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Add comment