Proms at Cadogan Hall 4, Connolly, Middleton review - perfect partnering in the unfamiliar | reviews, news & interviews

Proms at...Cadogan Hall 4, Connolly, Middleton review - perfect partnering in the unfamiliar

Proms at...Cadogan Hall 4, Connolly, Middleton review - perfect partnering in the unfamiliar

Songs about sleep keep the audience wide awake

“It has a music of its own. It produces vibrations.” Oscar Wilde was being ironic when he had Gwendolen contemplate the sound of her beloved’s drab name in The Importance of Being Earnest, but he had a point when it comes to composers and poetry. With their own “vibrations”, great poems rarely warrant musical interference; bad poetry, meanwhile, can resist even the finest scoring.

Take their opener. On the strength of her poem “A soft day”, it’s fair to say that we are unlikely to witness a Winifred M Letts (1882-1972) revival: “The soaking grass smells sweet/Crushed by my two bare feet… “ but that was before Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1954) got his hands on it. He uses that couplet to start a full-blooded rising phrase that blooms with Connolly’s most opulent tone. Then, spotting the lightness of touch in Stanford’s following descending phrase of single notes “Drips, drips, drips”, she and Middleton deftly touch in falling raindrops with extraordinary delicacy.

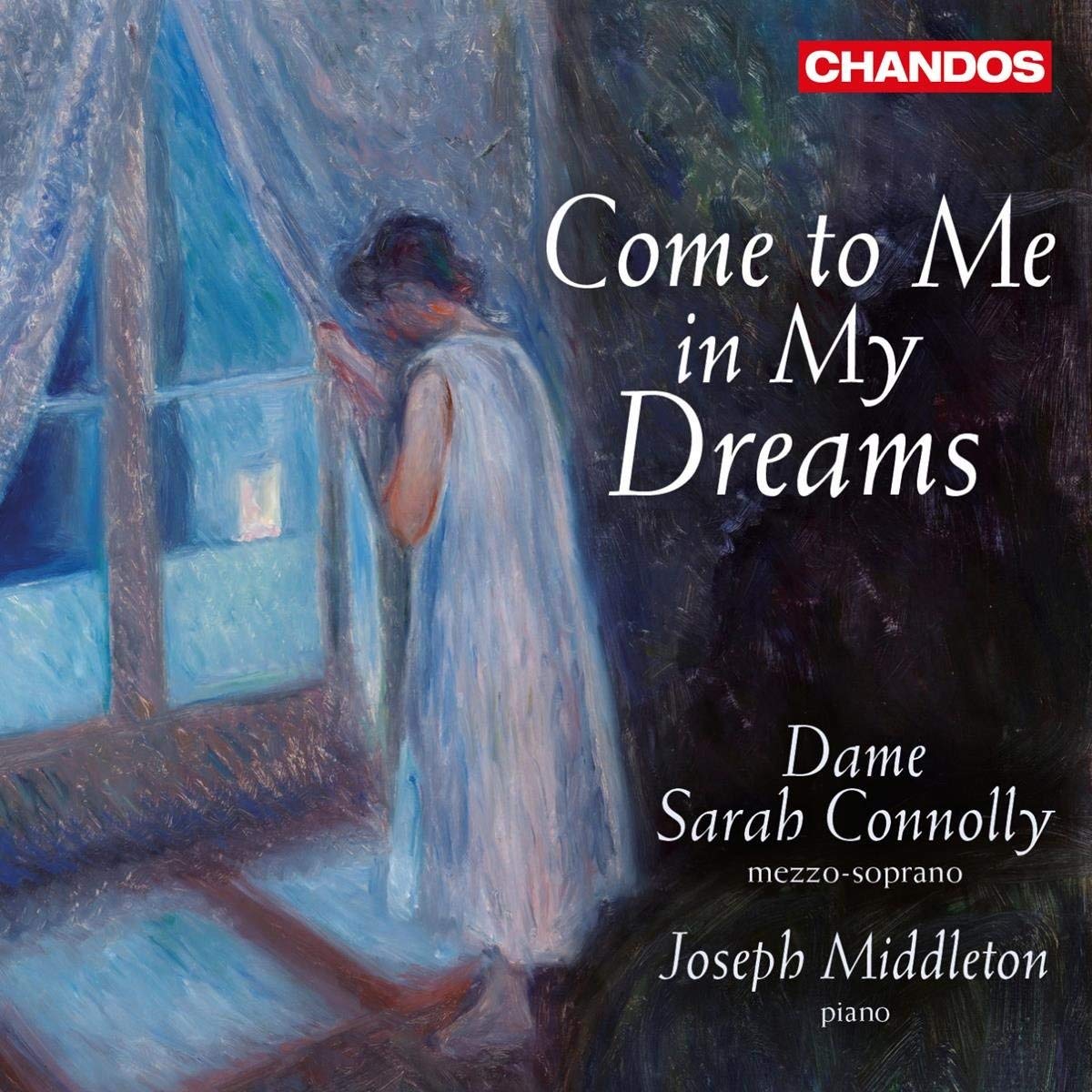

Their theme here – and throughout their recently released, more extended CD “Come to Me in My Dreams” – was not simply a collection of lullabies and dreamscapes. All the songs were written by composers through the 20th and 21st centuries who either studied or taught at the Royal College of Music over a span of 120 years.

Their theme here – and throughout their recently released, more extended CD “Come to Me in My Dreams” – was not simply a collection of lullabies and dreamscapes. All the songs were written by composers through the 20th and 21st centuries who either studied or taught at the Royal College of Music over a span of 120 years.

One of Stanford’s early students, Arthur Somervell, a song composer now known only to specialists, had taste assured enough to set “Into my heart an air that kills” from A Shropshire Lad by AE Housman. It’s the kind of subtle setting you could teach composition from. An eight-line poem in two verses, the first is so cunningly intense that you scarcely notice that every single word of it is sung on the same note. In Connolly’s performance it became a tiny masterclass in astonishingly varied expression.

Aside from her unusually wide expressive range under seemingly effortlessly control, the performance also outlined the fact that, with piano playing of this quality, “accompanied by” is an understatement. With Connolly ringing the changes on that single constantly re-expressed note, Middleton’s beautifully paced and placed playing was far more than mere support. The care in his phrasing and his understanding of structure allowed him to bring out all the tension in the carefully placed silences of Vaughan Williams’ “Love-Sight”, and his precision and quiet power in Frank Bridge’s arresting setting of Humbert Wolfe’s “Journey’s End” gave the constantly surprising harmonic progressions a sense of absolute purpose.

In the second half of the recital, Britten’s tiny cycle A Charm of Lullabies climaxed – if that’s the word for so gentle a set – with an outstanding performance of the final “The Nurse’s Song”, the most “Brittenish” of the five songs. You can tell a very great deal about a singer’s technique (and taste) by the way they finish a phrase and Connolly’s closing of the song was remarkable. Britten loses his trademark wry harmonies for the final verse which is sung unaccompanied, leaving the preceding harmonies to hang in the air as wistful memories. Dropping to the low glow at the bottom of her register, Connolly produced pianissimo yet utterly focused and energised singing, the sound vanishing perfectly to the deep dark silence of sleep.

In the second half of the recital, Britten’s tiny cycle A Charm of Lullabies climaxed – if that’s the word for so gentle a set – with an outstanding performance of the final “The Nurse’s Song”, the most “Brittenish” of the five songs. You can tell a very great deal about a singer’s technique (and taste) by the way they finish a phrase and Connolly’s closing of the song was remarkable. Britten loses his trademark wry harmonies for the final verse which is sung unaccompanied, leaving the preceding harmonies to hang in the air as wistful memories. Dropping to the low glow at the bottom of her register, Connolly produced pianissimo yet utterly focused and energised singing, the sound vanishing perfectly to the deep dark silence of sleep.

Better yet, she and Middleton performed the world premieres of two songs they’d uncovered in the Britten archives which the composer wrote for but cut from the final cycle. “Somnus, the humble God” is (very) minor Britten but “A Sweet Lullaby” is a find, the accompaniment slowly rocking and rippling, the harmonies plangent.

The only mild disappointment was the six-minute Proms commission, “Sleeplessness … Sail”. Although Lisa Illean’s setting of an Osip Mandelstam translation aims for visions inspired by Homer during restlessness, the song merely conveyed a languid sense of stasis. Richer by far was Mark-Anthony Turnage’s “Farewell”. Connolly has been singing Turnage’s music since 2000 when she created the role of Susie in his opera The Silver Tassie. Written for her, the song spans two octaves of her voice, a challenge she meets not just with clarity of diction at both ends but with sensitivity to both the wit of Stevie Smith’s bleakly cheerful words but also the ardour and melancholy of the music. What more could a composer – and an audience – ask for?

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment