Tones, Drones and Arpeggios: The Magic of Minimalism, BBC Four - brilliant appraisal | reviews, news & interviews

Tones, Drones and Arpeggios: The Magic of Minimalism, BBC Four - brilliant appraisal

Tones, Drones and Arpeggios: The Magic of Minimalism, BBC Four - brilliant appraisal

Overdue survey of a subversive musical idea gone defiantly mainstream

By most measures, minimalism is the most successful movement in 20th-century music, certainly orchestral music.

So widespread now is the influence of minimalism, with many a MOR-ish piano ensemble aspiring to an inoffensively contemporary wash of sound using minimalist techniques in watered-down form, it’s difficult to believe how small it once was, yet how revolutionary most of its techniques. In Tones, Drones and Arpeggios: The Magic of Minimalism (BBC Four) Charles Hazlewood illustrates both with great clarity, with first the wild conceptual visions of La Monte Young and his unfinishable piece The Well-Tuned Piano, to the brilliant but more customisable synth pioneers at the San Francisco Tape Music Centre, whose inventions went on to influence vast areas of contemporary music, from Mike Oldfield to Kraftwerk.

Minimalism undermines the three-part melodic structure of the Western tradition. It dispenses with the concept of time moving towards a conclusion, replacing it with intense repetition and highly focused attention to rhythmic and harmonic detail. The mesmeric use of long drone notes came, in the principal foreign influence on an otherwise Californian invention, from the Indian classical tradition. Terry Riley still practises his ragas (microtonal scales) daily, we learned. All of this was illustrated rather brilliantly.

The broader cultural context was also well sketched, with useful coverage of Young’s involvement in the Fluxus movement, and its awareness of audience interaction as part of a performance. Although the most influential individual minimalists, Steve Reich and Philip Glass, made their names in New York, Young argued that the concept, particularly its sense of endless time, was quintessentially a Californian one.

The broader cultural context was also well sketched, with useful coverage of Young’s involvement in the Fluxus movement, and its awareness of audience interaction as part of a performance. Although the most influential individual minimalists, Steve Reich and Philip Glass, made their names in New York, Young argued that the concept, particularly its sense of endless time, was quintessentially a Californian one.

Tape technology, then the cutting edge, of course, was crucial to several techniques of minimalism, specifically the incorporation of distortion, which increases with each repetition of a loop, and phasing, whereby two identical samples played on adjacent tape machines will gradually begin to play out of sync. The studio demonstrations of both, with the help of Portishead’s Adrian Utley, were superb.

Occasionally the contextual pondering got out of hand, though entertainingly so. Jarvis Cocker suggested that the “sawing violas” in the Velvet Underground were inspired by the experiences of John Cale and Angus MacLise, who played with La Monte Young in the '60s. This is entirely reasonable. But the notion that this in turn prepared audiences to accept minimalism as mainstream music perhaps joins some distant dots over-enthusiastically.

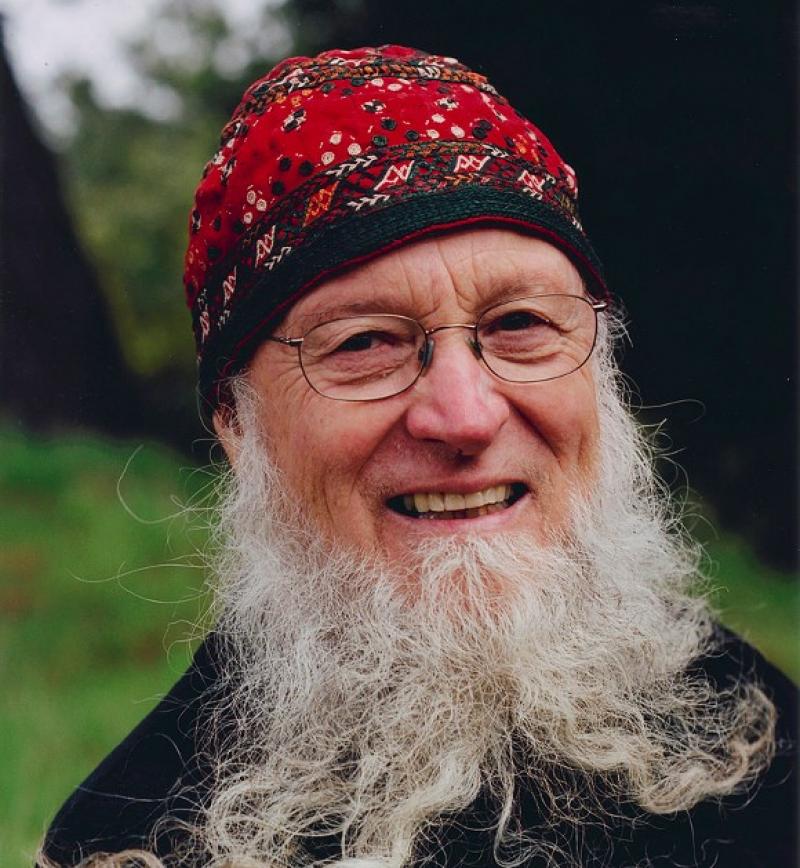

Hazlewood (pictured above) described minimalism as the “last big idea in classical music”. What comes next (death? The eternal hegemony of Delius season on Classic FM?) he didn’t say. Young and Riley were acclaimed as Californian pioneers, prophets without honour, and visionaries who pre-scored the road ahead with a sense of fun that is gradually taking over the traditional world of classical music. Minimalists and what’s left of the serialists of the European avant-garde have a tense and generally disrespectful relationship, exemplified by Philip Glass’s description of some serialists as creeps and maniacs. There will be more of this next week.

Charles Hazlewood is a classical conductor by training, but has been a broadcaster for over a decade, and has impeccable credentials as a breaker of musical boundaries, and a supporter of minimalism. He’s even taken Steve Reich to Glastonbury, giving the first headline orchestral performance at the festival. There was an excellent sequence of concise exposition about Riley’s revolutionary piece In C, described by Hazlewood as the “big bang of minimalism”, and “democracy in action”. Around a central pulse, it gives performers an autonomy to unparalleled in any earlier scored piece.

Here, perhaps, was an opportunity for Hazlewood to reach out beyond the intimate community of professional musicians who occupied the rest of the programme, and give us a sense of how minimalism has changed the wider music scene, beyond the pontifications of Jarvis Cocker. If there’s a caveat, both of the music and this programme, it’s that, though widespread geographically, minimalism has mostly remained a white, male, middle-class music, unlike the jazz and rock that emerged from San Francisco in the '50s and '60s.

Otherwise, within the well-established arts-doc formula, this was a model of brisk, cogent, and incisive comment. La Monte Young, whose influence is both broad and deep, has never been broadcast on the BBC before, so his footage alone made the programme worthwhile, even for those already familiar with the central ideas of the music. A mainstream appraisal of the revolution he and Riley began has long been overdue.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

Add comment