theartsdesk in Oslo: Two Peer Gynts and a Hamlet | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Oslo: Two Peer Gynts and a Hamlet

theartsdesk in Oslo: Two Peer Gynts and a Hamlet

Intermittently powerful new Ibsen opera outshone by hard-hitting Norwegian theatre

Not so much a national hero, more a national disgrace. That seems to be the current consensus on Peer Gynt as Norway moves forward from having canonized the wild-card wanderer of Ibsen's early epic. It’s now 200 years since Norway gained a constitution, and 114 since Peer first shone in the country's National Theatre, that elegant emblem of the Norwegian language.

Alexander Mørk-Eidem took the question as the starting point of his electrifying new Ibsen production at the National Theatre framed as a TV chat show where Peer, reaching 50, gets to deal with his mid-life crisis. State-of-the-nation considerations never figured for Estonian-born, Berlin-based composer Jüri Reinvere in his opera, receiving its world premiere at the fabulous National Opera the night after I saw the play. He deliberately avoided the attempt to discover Norway further, resisting the chance to spend extended time there, contemplating instead a wider situation, at least within Europe, and going more consciously for the universal and the metaphysical with a libretto that contains a very low percentage of Ibsen’s original lines.

What a beautiful and musical language Norwegian isBoth approaches are valid, and many more besides, as the productions I’ve seen over the years have so richly demonstrated. The biggest genius of Ibsen, it seems to me, is not only to embrace multitudes of meanings but to shift with the perspectives of the times. And Peer is the slipperiest eel of them all. Some would say the play is unstageable. The heroine of Willy Russell’s Educating Rita, faced with the essay question "Suggest how you would resolve the staging difficulties inherent in a production of Ibsen's Peer Gynt," writes simply “Do it on the radio”.

Fair enough, that leaves the listener’s imagination free to roam. But most of us want to see how directors, composers and designers respond to dilemmas we may not have discovered in the drama ourselves. Which is why I count the Oslo weekend one of the best engagements with aspects of a culture I’ve ever enjoyed abroad, enriched by a superlative and original Hamlet as well as a long-postponed visit to the Ibsen Museum in his apartment near the Royal Palace.

My first morning before the noon performance of the play started with a very necessary briefing from the National Theatre’s Kirsti Ellefsen. Since Mørk-Eidem has substantially reworked the text, and my Norwegian is virtually non-existent, it certainly helped to know certain details: for instance, that the company in the Hall of the Mountain King, with its motto "Be yourself, and to hell with the rest of the world", consists of Norwegian celebrities and politicians (many pictured, right, around Eindride Eidsvold's Peer Gynt), all well known within the country for having been compromised in their worldliness in one way or another.

My first morning before the noon performance of the play started with a very necessary briefing from the National Theatre’s Kirsti Ellefsen. Since Mørk-Eidem has substantially reworked the text, and my Norwegian is virtually non-existent, it certainly helped to know certain details: for instance, that the company in the Hall of the Mountain King, with its motto "Be yourself, and to hell with the rest of the world", consists of Norwegian celebrities and politicians (many pictured, right, around Eindride Eidsvold's Peer Gynt), all well known within the country for having been compromised in their worldliness in one way or another.

As the king himself, the "Old Man of Dovre", Finn Schau impersonates Olav Thon, farm boy turned billionaire real-estate developer, who goes around in a woolly hat (he also loves the theatre and wants to leave his money to a foundation for medical research). The other actors-as-trolls represent Prime Minister Erna Solberg, her bad-taste lipstick dress duly reproduced, Siv Jensen the Minister of Finance who was accused of being "spineless" when she backtracked on a promise and so wobbles around the stage without a backbone, gay media personality Jan Thomas, sports stars Theresa Johaug and Petter Northug, and Ari Behn, the maverick author who married into the royal family. The Troll King’s Daughter, who appears to Peer as the Woman in Green, is an artificially enhanced bimbo who grows more grotesque once she’s sired a son by our hero.

Perhaps you don’t need to know all the details to enjoy a scene for which Grieg, working on the incidental music never heard here, described his famous number as "smacking so much of cow dung, ultra-Norwegianism and self-satisfaction that I quite literally cannot bear to listen it it," but it helps. Besides, there are some stylised shocks here: after a bizarre and very funny sex romp with the green dame, Peer spits out a swig of urine pissed into a glass by the Northug character and suffers painful anal penetration to insert his troll-tail

T he antihero, whom we see cracking up on telly as he hears the voice of his dead mother Åse (Anne Kringsvoll), needs colossal energy and strong verse-speaking, both of which he gets from fearless Eindride Eidsvold; what a beautiful and musical language this is. Solveig, the woman who will wait however long it takes for Peer to learn a lesson from life, becomes Shamso as played by the Nigerian-Norwegian singer-songwriter Amina Sewali (pictured, above, with Eidsvold and Mattis Herman Nyqvist as TV presenter Fredrik Skavlan; both National Theatre images by Gisle Bjørneby). In her production which recently came to the Barbican, Irina Brook used an Indian dancer to convey Solveig’s otherness – in the original, she comes from the village over the mountain, so she’s already set apart – but gave her nothing like this lady’s independence, dignified sensuality and presence. Sewali sings not only familiar pop standards but her own numbers – still a bit too mundane for the play’s stranger or quieter moments, but delivered with a haunting lower register that only goes into conventional above the break. As Peer sells out through the first part of the second half, we see her slump into depression, but the homecoming has a lethal outcome – not just the welcome-back to truth residing in the eternal feminine, but a clever epilogue of lines from other Ibsen plays: like Nora in A Doll’s House, Shamso walks out on her man at the end.

he antihero, whom we see cracking up on telly as he hears the voice of his dead mother Åse (Anne Kringsvoll), needs colossal energy and strong verse-speaking, both of which he gets from fearless Eindride Eidsvold; what a beautiful and musical language this is. Solveig, the woman who will wait however long it takes for Peer to learn a lesson from life, becomes Shamso as played by the Nigerian-Norwegian singer-songwriter Amina Sewali (pictured, above, with Eidsvold and Mattis Herman Nyqvist as TV presenter Fredrik Skavlan; both National Theatre images by Gisle Bjørneby). In her production which recently came to the Barbican, Irina Brook used an Indian dancer to convey Solveig’s otherness – in the original, she comes from the village over the mountain, so she’s already set apart – but gave her nothing like this lady’s independence, dignified sensuality and presence. Sewali sings not only familiar pop standards but her own numbers – still a bit too mundane for the play’s stranger or quieter moments, but delivered with a haunting lower register that only goes into conventional above the break. As Peer sells out through the first part of the second half, we see her slump into depression, but the homecoming has a lethal outcome – not just the welcome-back to truth residing in the eternal feminine, but a clever epilogue of lines from other Ibsen plays: like Nora in A Doll’s House, Shamso walks out on her man at the end.

The image which will stay with me forever, though, strikes at the point in Ibsen’s play where a storm wrecks the ship bringing a disillusioned Peer back to Norway. Never has a dry-ice machine been more shockingly engaged, pumping out smoke in a hurricane at high velocity as the TV studio collapses, its tinsel lying like unspooled tape over the floor, and we see an astonishing artwork on the back wall as a bloodied Peer emerges from the wreckage. It’s To Everything There is a Season by Norwegian-based artist Vanessa Baird (detail pictured, above), a work which has created much controversy since; although it was painted for an Oslo public space before Breivik's terrorist attack and massacre it seemed to anticipate those terrible events with its flying pieces of paper and its crumbling high rise. Norway, Mørk-Eidem indicates albeit obliquely, went into shutdown after the crisis; it’s a good reason for placing the death of Åse here rather than at the end of the first Norwegian segment of the play. And the effect sent me into shock, surrounded as I was by Norwegian schoolchildren of all races, headscarved girls included, sitting so attentively through the matinee. They all rose to their feet instantly at the end of a three and a half hour drama which was never less than engaging.

The image which will stay with me forever, though, strikes at the point in Ibsen’s play where a storm wrecks the ship bringing a disillusioned Peer back to Norway. Never has a dry-ice machine been more shockingly engaged, pumping out smoke in a hurricane at high velocity as the TV studio collapses, its tinsel lying like unspooled tape over the floor, and we see an astonishing artwork on the back wall as a bloodied Peer emerges from the wreckage. It’s To Everything There is a Season by Norwegian-based artist Vanessa Baird (detail pictured, above), a work which has created much controversy since; although it was painted for an Oslo public space before Breivik's terrorist attack and massacre it seemed to anticipate those terrible events with its flying pieces of paper and its crumbling high rise. Norway, Mørk-Eidem indicates albeit obliquely, went into shutdown after the crisis; it’s a good reason for placing the death of Åse here rather than at the end of the first Norwegian segment of the play. And the effect sent me into shock, surrounded as I was by Norwegian schoolchildren of all races, headscarved girls included, sitting so attentively through the matinee. They all rose to their feet instantly at the end of a three and a half hour drama which was never less than engaging.

There was more stylized violence that evening in an optional extra over at the Norwegian Theatre, Oslo's other major theatre company which also puts on musicals and children’s shows. I happened to be walking past it after the matinee, liked the idea of a Hamlet played by a woman, with the roles of both Horatio and Ophelia taken by a man, and thought I knew the play well enough to cope with the Norwegian (I hadn’t reckoned on a screen scene between Hamlet and a Norway-famous telly astrophysicist back in Oslo after the protagonist has bludgeoned Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to death on the boat back from Elsinore, but it was still funny without a grasp of the text). I was lucky to get into the relatively small Scene Two downstairs that evening (both the Norwegian Theatre Hamlet and the National's Peer Gynt are sell-out shows, I'm told).

Young director Peer Perez Øian’s mostly Shakespeare-faithful three-hour show is set on a more or less bare stage, with only a miniature theatre which can be wheeled around and a hook from which is suspended in turn a glitter ball, a cardboard moon (by Hamlet), a cabbage (for Ophelia’s mad scene) and a skeleton towards the final body count. The eight actors wear masks modelled on their own faces and each plays several roles, with the exception of Marie Blokhus’s Hamlet (pictured, above, with Mads Ousdal's Claudius; both Norwegian Theatre images by Dag Jenssen). Blokhus has all the eloquence for the soliloquies and an impotent rage which never becomes too shouty. This is Hamlet as a teenage girl, crucially so when the jeans and T shirt give way to a skirt as stepfather Claudius turns to stylized abuse.

Young director Peer Perez Øian’s mostly Shakespeare-faithful three-hour show is set on a more or less bare stage, with only a miniature theatre which can be wheeled around and a hook from which is suspended in turn a glitter ball, a cardboard moon (by Hamlet), a cabbage (for Ophelia’s mad scene) and a skeleton towards the final body count. The eight actors wear masks modelled on their own faces and each plays several roles, with the exception of Marie Blokhus’s Hamlet (pictured, above, with Mads Ousdal's Claudius; both Norwegian Theatre images by Dag Jenssen). Blokhus has all the eloquence for the soliloquies and an impotent rage which never becomes too shouty. This is Hamlet as a teenage girl, crucially so when the jeans and T shirt give way to a skirt as stepfather Claudius turns to stylized abuse.

I thought this was going to be mannered Regietheater, but nearly every detail made sense. There’s appropriately Shakespearean imagery in Claudius as a rutting dog, disturbingly reflected in the images for the players’ re-enactment of what here is the Clytemnestra-Agamemnon-Aegisthus triangle. Vidar Magnussen’s smug and superbly-spoken courtier Polonius yields to the actor’s Gravedigger as skeleton puppeteer, consummate and brilliant – and each subsequent death simply means peeling off a garment to reveal skeleton-printed clothes beneath. Mads Ousdal, as Hamlet’s father and stepfather, speaks the verse beautifully, while there’s virtuosity from Frank Kjosås (pictured, above), Blokhus’s real-life husband, not only moving effortlessly between playing Horatio and a male Ophelia but also producing soundtracks for the play-within-the-play’s musical numbers. Again the only false note for me was the background music, this time rather feeble synth stuff from Lucy Swann. So the score was the one dimension in the opera that could possibly cap what I’d seen already.

I thought this was going to be mannered Regietheater, but nearly every detail made sense. There’s appropriately Shakespearean imagery in Claudius as a rutting dog, disturbingly reflected in the images for the players’ re-enactment of what here is the Clytemnestra-Agamemnon-Aegisthus triangle. Vidar Magnussen’s smug and superbly-spoken courtier Polonius yields to the actor’s Gravedigger as skeleton puppeteer, consummate and brilliant – and each subsequent death simply means peeling off a garment to reveal skeleton-printed clothes beneath. Mads Ousdal, as Hamlet’s father and stepfather, speaks the verse beautifully, while there’s virtuosity from Frank Kjosås (pictured, above), Blokhus’s real-life husband, not only moving effortlessly between playing Horatio and a male Ophelia but also producing soundtracks for the play-within-the-play’s musical numbers. Again the only false note for me was the background music, this time rather feeble synth stuff from Lucy Swann. So the score was the one dimension in the opera that could possibly cap what I’d seen already.

Next page: the Ibsen Museum and Reinvere's operatic Peer Gynt

Before that, on an oppressively dark and cold Sunday afternoon, I made my way over to the Ibsen Museum which includes the apartment the writer, his wife and son occupied in the last eight years of his life, and where he wrote his final plays, John Gabriel Borkman and When We Dead Awaken. As well as the painstakingly reconstructed lifestyle in the flat proper, the museum also has space for exhibitions, including a tantalizing conception of old Ekdal's attic garden for his wild duck and other animals as a flowering plant of eggs by Lucie Noel Thune.

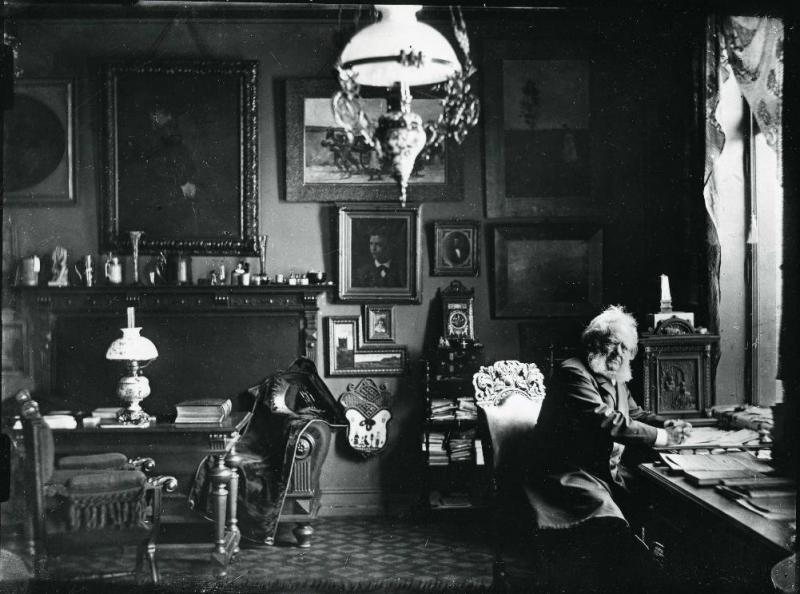

Leasing the palatial suite of rooms in 1895 shortly after the block had been built, Ibsen constructed an edifice of the perfect bourgeois life so relentlessly subverted in many of his plays. He had a bath installed before there was one in the Royal Palace opposite; he created interiors respectively modelled on French, Italian and Scandinavian styles, and he entertained reporters in his study (pictured by Anne-Lise Reinsfelt) which, unlike the library where his long-suffering wife Suzannah spent most of her time, was selectively open to the public gaze.

Leasing the palatial suite of rooms in 1895 shortly after the block had been built, Ibsen constructed an edifice of the perfect bourgeois life so relentlessly subverted in many of his plays. He had a bath installed before there was one in the Royal Palace opposite; he created interiors respectively modelled on French, Italian and Scandinavian styles, and he entertained reporters in his study (pictured by Anne-Lise Reinsfelt) which, unlike the library where his long-suffering wife Suzannah spent most of her time, was selectively open to the public gaze.

Though the rooms were dismantled after Suzannah’s death in 1914, all save the library were documented in photographs and have been meticulously reconstructed with the original furniture and, where possible, artworks. The dim lighting on a dark day and the glass door through which you have to peer at the master’s workspace mean you can hardly see the strangest of the study trophies – distinguished Norwegian artist Christian Krohg’s superb portrait of Strindberg hanging above one of the desks. Ibsen purchased it and put it there to represent “the outbreak of madness”, making sure it would goad him to work hard in his own fashion.

From the excellent responses to our questions by guide Frøydis Århus, who had recently completed her PhD on Mark Ravenhill and wondered what I thought about this future librettist of another new opera for Norway, we came to the conclusion that a biography ought also to be written about the fascinating Suzannah. Famously she told her husband that the alternative ending for the German premiere of A Doll’s House, where at the actress's request Nora stays with her husband, was unacceptable: "Either she goes, or I do". What a woman, however bound to the conventional precepts of the time about the artist’s helpmate.

While in the National Theatre production Sewali’s Shamso/Solveig becomes a Nora who walks out, the opera I saw that evening kept its women in the usual roles of angels or whores. Indeed, there wasn’t much interest evident in the main characters: Nils Harald Sødal’s Peer (pictured, left, in the opera's most shocking scene; National Opera images by Erik Berg) was a lightish cipher rather than the Heldentenor we surely need for the huge personality of Ibsen’s protagonist. Nor was composer Reinvere’s concept of the opening sequence where Peer meets Solveig (Marita Sølberg, poised lyric soprano) at former girlfriend Ingrid’s wedding and abducts the bride my idea of what’s needed here, which is surely an establishing of Peer’s youthful exuberance and boastfulness. The orchestral prelude instead establishes a slow, dark continuum of late romantic sound which might be rooted anywhere, timewise, between Mahler’s Tenth Symphony and Berg’s Wozzeck, before Straussian dance rhythms take over. One thing's for sure: the orchestra of the National Opera burns and glows under its chief conductor John Helmer Fiore.

While in the National Theatre production Sewali’s Shamso/Solveig becomes a Nora who walks out, the opera I saw that evening kept its women in the usual roles of angels or whores. Indeed, there wasn’t much interest evident in the main characters: Nils Harald Sødal’s Peer (pictured, left, in the opera's most shocking scene; National Opera images by Erik Berg) was a lightish cipher rather than the Heldentenor we surely need for the huge personality of Ibsen’s protagonist. Nor was composer Reinvere’s concept of the opening sequence where Peer meets Solveig (Marita Sølberg, poised lyric soprano) at former girlfriend Ingrid’s wedding and abducts the bride my idea of what’s needed here, which is surely an establishing of Peer’s youthful exuberance and boastfulness. The orchestral prelude instead establishes a slow, dark continuum of late romantic sound which might be rooted anywhere, timewise, between Mahler’s Tenth Symphony and Berg’s Wozzeck, before Straussian dance rhythms take over. One thing's for sure: the orchestra of the National Opera burns and glows under its chief conductor John Helmer Fiore.

Reinvere’s music and libretto have their own self-limited but fascinating take on Ibsen’s epic. The composer evidently loves the natural universe that envelops his hero; there are beguiling forest murmurs around the trolls and maidens of the mountains, and the point at which the music stops around Åse’s death at the end of the First Act and ambient sounds take over is hypnotic. Reinvere also writes a virtuoso part for the soprano range of counter-tenor David Hansen as the nothingness that is the Great Bøyg (pictured, above), and Hansen executes an even more giddying phrase or two as the Cheshire Cat (you may well do another take, but that's Reinvere's version of Ibsen's Sphinx). Even so Grieg’s minimalism for the Bøyg scene, harping on a tritone, is surely much more effective than Reinvere’s generic crunches of sound.

Reinvere’s music and libretto have their own self-limited but fascinating take on Ibsen’s epic. The composer evidently loves the natural universe that envelops his hero; there are beguiling forest murmurs around the trolls and maidens of the mountains, and the point at which the music stops around Åse’s death at the end of the First Act and ambient sounds take over is hypnotic. Reinvere also writes a virtuoso part for the soprano range of counter-tenor David Hansen as the nothingness that is the Great Bøyg (pictured, above), and Hansen executes an even more giddying phrase or two as the Cheshire Cat (you may well do another take, but that's Reinvere's version of Ibsen's Sphinx). Even so Grieg’s minimalism for the Bøyg scene, harping on a tritone, is surely much more effective than Reinvere’s generic crunches of sound.

The most powerful musical gestures occur at exactly the point where Mørk-Eidem’s production stuns in a generally more engaging experience. The adventures of Reinvere’s Peer abroad take him to a Roman abattoir where the cattle are human beings tired of life. Horrifying choral wails combine with the most powerful of director Sigrid Strøm Reibo’s resourceful stage pictures (her achievement, much heightened by some stupendous designs from Katrin Nottrodt – Cairo madhouse scene pictured – marks her out as a young director of enormous promise). Then both the music and the drama go beyond to the trangressive scene in which Peer realizes – or does he? – his strongest innermost desire: to be a mass murderer, and an overwhelming funeral march, Reinvere's most distinctive inspiration, unfolds after the gunshots. Like Nicholas Maw in the last act of his much-maligned opera based on Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, Reinvere reaches deep for music that really does match the horror of the action at the peak of the second act’s Mahlerian musical curve.

The most powerful musical gestures occur at exactly the point where Mørk-Eidem’s production stuns in a generally more engaging experience. The adventures of Reinvere’s Peer abroad take him to a Roman abattoir where the cattle are human beings tired of life. Horrifying choral wails combine with the most powerful of director Sigrid Strøm Reibo’s resourceful stage pictures (her achievement, much heightened by some stupendous designs from Katrin Nottrodt – Cairo madhouse scene pictured – marks her out as a young director of enormous promise). Then both the music and the drama go beyond to the trangressive scene in which Peer realizes – or does he? – his strongest innermost desire: to be a mass murderer, and an overwhelming funeral march, Reinvere's most distinctive inspiration, unfolds after the gunshots. Like Nicholas Maw in the last act of his much-maligned opera based on Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, Reinvere reaches deep for music that really does match the horror of the action at the peak of the second act’s Mahlerian musical curve.

Not that the Norwegian critics, by all accounts, have really taken it into account. There’s simply been outrage at another, more explicit evocation of the life-changing Norwegian catastrophe, with an especially indignant attack coming from a famous former Peer Gynt at the National Theatre, Toralv Maurstad. Well, debate is healthy – and since Reinvere’s music renders his creative licence so much more than gratuitous, it can’t be a bad thing. After all, what was Breivik if not the ultimate representative of the Troll King’s motto, “Be yourself – and to hell with the rest of the world”? A chance to catch Reinvere's work at the Royal Opera or ENO would be welcome, but it's this play Peer Gynt and the Hamlet in a future Barbican season of international theatre that everyone needs to see here.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment