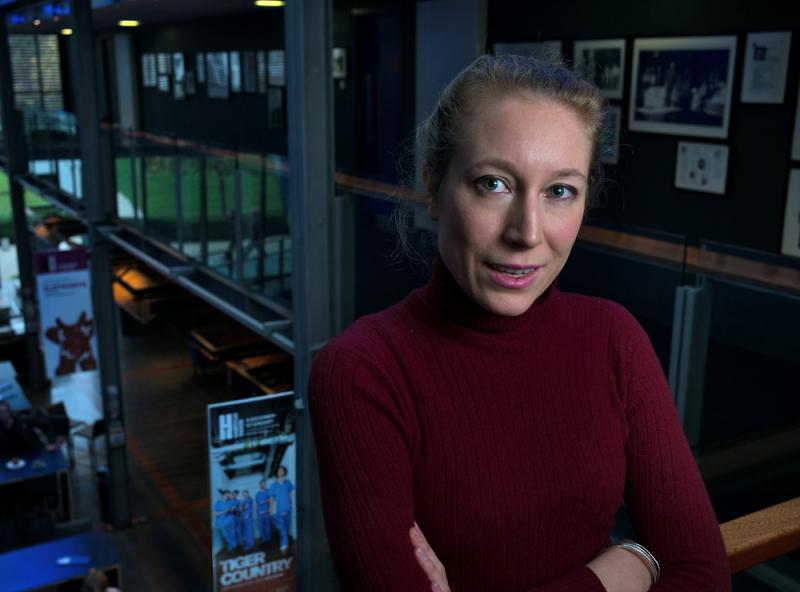

theartsdesk Q&A: Playwright Nina Raine | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Playwright Nina Raine

theartsdesk Q&A: Playwright Nina Raine

As a hit play about the NHS returns, the author-director explains its creation

When writers research, it’s not all about digging for facts. Feelings also count. When Nina Raine spent three months visiting hospitals for a play about the medical profession, she found a strange feeling spontaneously erupting inside herself. “The funny thing is I was getting up early for me, 6.30, to get on a bus to be at the place by a quarter to eight and I just started within a week to feel like a put-upon doctor saving people’s lives. Don’t these people realise I’m going to hospital?

For a play which, rarely for theatre, aims to show the way doctors live and work and above all think, it was a valuable insight. The play is Tiger Country. It opened to high praise at the Hampstead Theatre in 2011, and now makes a welcome return with Indira Varma leading the cast. As before, Raine will also direct (among plays she has directed are April de Angelis's Jumpy at the Royal Court and in the West End, and William Boyd's Chekhov adaptation Longing for Hampstead.)

Her playwriting career began in 2006. Rabbit centred on a rudderless young woman of nearly 30 who celebrated her birthday with friends while her father was dying in hospital. It opened at the Old Red Lion in North London and ended up in the Brits Off Broadway season in New York. Then four years later came Tribes at the Royal Court. It featured at its heart another father, this one a vibrant patriarch in very rude health who heads a voluble family from which a deaf member feels a mounting sense of exclusion.

Her father is the poet Craig Raine, her mother the literary academic Ann Pasternak Slater. Their daughter explains to theartsdesk how early on that she began writing for the stage rather than the page.

JASPER REES: Why a play about hospital?

NINA RAINE: I had this character from Rabbit who was a doctor. A dad. And then I had a dad in Tribes as well. Things pique your imagination. I thought I’d quite like to see where this doctor goes. I had a friend who was working as a doctor in a hospital and it sounds banal but if you’re working in theatre you get very worked up if you get a bad review. If your doctor friend cocks up a tiny bit someone dies. She was quite young when I wrote Rabbit. She was having to tell people they were going to die. It just felt really fascinating that you’ve got these quite young unformed people having to develop a personality for doing this kind of work or job before they even know who they really are. I got interested in what it does to your personality and your personal life. It can’t help but seep into how down to earth and brusque you might be with your romantic partner if you’re coming from a day when you’ve just had to pull the plug on someone or have had a failed cardiac arrest. It’s got to have an impact. It’s almost like a war zone where only the shell-shocked can understand, but at the same time they might be weirdly not quite as sympathetic as a civilian.

How did you go about researching this area in which feelings are so cauterised?

I did a lot of watching. I watched some operations. I hung out in those mess rooms that are near operating theatres. It’s a bit like the green room for actors. Off-duty doctors talking off the record. I also got to see doctors on the ward. They’d always say, “This is Nina, she’s researching a play.” No one ever said, “Well, I don’t want her present.” People are much more focussed on what the doctor is going to give them. They do have to cauterise. This friend of mine is the sweetest girl ever, but it’s fascinating when you say, “I’ve got this pus on my tonsils,” she’ll say, “OK, what colour pus is it?” It won’t be, “Oh poor you.” It’s intellectual curiosity. It’s like a detective at work. The emotion is curiosity and intelligence at work. She is the most touchy-feely doctor. What other doctors also say to me is they cauterise themselves and then one of their own relatives gets caught in the system and then they feel incredibly weird because they’ve got half of them that’s being the daughter or the cousin or the niece and then they’re used to all those parts being switched off in the hospital. They want to control the situation and yet there are all these codes. It’s a really rich field emotionally if you can do it in a way that doesn’t get all television and small and flabby.

Did you know the stories you wanted to tell beforehand? (Original production of Tiger Country pictured right by Robert Workman)

Did you know the stories you wanted to tell beforehand? (Original production of Tiger Country pictured right by Robert Workman)

I knew I wanted to tell the story about the Rabbit character. And then I didn't really know. I went into it fairly open-mindedly. There were far too many stories to put into one play. And you realise all these things you didn’t realise and they become part of the play. I think I had one bone and the rest was fleshed out.

Which hospitals did you visit?

A couple in London, one in Oxford, one in East Grinstead.

What sort of things turned up in the research process?

I sometimes spent a really boring three days of seeing nothing and then you’d see amazing things. I was following a team around. You have to let them forget and start to become one of the team. The patient is always asked so there’s never any confidentiality issue. You’ve got to be really careful when writing a play. When I’m saying to a doctor, “So tell me, have you ever killed anyone by mistake?”, it’s really interesting when they might tell you, “Yes technically I suppose I did kill this patient although they were going to die anyway.” And you think, oh that’s such a good story, but if everyone is a doctor it’s actually quite hard to crowbar in a story where a doctor tells another doctor. They wouldn’t tell it to another doctor the way they tell it to a lay person. It would be perfect for the audience but it has no reality in the play. So I had to junk quite a lot of stuff that I really adored hearing.

I do want to make it real. Doctors are all people so they’re very different. One slapdash doctor will read it and go, “It’s fine, what are you worrying about?” I go, “The thing is someone else read it and they said. ‘Now it’s really easy to get CT scans, you can get them like Smarties.’ I’ve got a whole scene where someone is bargaining to get a CT scan.” “Yeah but who is going to be noticing that? That was more like three years ago.” I was like, “The very least I can do is to get it right for now.” All it needs is for one doctor to come and see it and write a snotty article saying, “Got all these things wrong,” and suddenly the play has lost a vital element which is that it should be real.

There were four years between Rabbit and then Tribes and Tiger Country. What happened?

I wrote Tiger Country before Tribes. But it took me ages to write it. It was so huge and sprawling. I’d spend a bit of time in hospital and come out and write it and then I’d think, no I really need to go back to the hospitals again. These doctors are so sweet. They just kept letting me come back. So actually post Rabbit a lot of time was spent writing Tiger Country and then Tribes. That’s two plays in four years. I think that’s all right actually. Tiger Country took ages to write, ages to research, ages to boil it down. Tribes happened a teeny bit more quickly but even with that I wanted to learn a teeny bit of sign because I felt unconfident writing scenes in sign language when I had never learnt any sign. I did a basic course and did an exam. I really didn’t want to do the exam but it turned out that the teacher got points for each student that sat the exam so she made us sit it. I passed. I did quite well in some places and not in others.

Overleaf: 'Everyone thinks, Ooh, are you going to be a poet too?'

You directed Rabbit and Tiger Country but over the years have had other roles in the rehearsal room. Has that been useful?

You directed Rabbit and Tiger Country but over the years have had other roles in the rehearsal room. Has that been useful?

Being an assistant director is a great way of finding time to write. You get wonderful dream time and no pressing angst. A bit of politics maybe with the director or feeling you have to say something intelligent. And you’re watching and learning all the time – what kind of scene is effective? I wrote Rabbit while I was assisting. I assisted John Caird in What the Night Is For with Gillian Anderson. It was actually really helpful. With Roger Michell directing Tribes it was like returning to assistant directing. It was like watching a master at work, purloining a few tricks for my own bag. I felt gloriously responsibility-free.

Not many playwrights direct their own work. Does it lead to complications?

We were going through Tiger Country. One of the actors suddenly burst out, “But you know all the answers. Why are you asking us?” The thing is I don’t know all the answers. And it’s not about me going, “Here’s a fact sheet, I did it up last night, any questions should be covered here.” It’s about discovering it together. Also people will ask you questions and come up with answers that you wouldn’t have thought of it. You’ve got to be open to that. The thing the writer does have is something the director has. Privately you’ve got a sense of how the scene should sound. Actors always want to deliver a scene with lower stakes because it’s more comfortable. Actually you always have to make them go up a gear. Writers often have that inner ear but no way of communicating it tactfully to the actor. And some shit directors don't have that inner ear although they have the means to communicate with the actor freely. When you get a jackpot like Roger – he’s got the inner ear and the ways of manipulating actors tactfully and tastefully – then you’ve got everything you want.

Are you in any shape or form going about your father’s business?

Everyone thinks, “Ooh, are you going to be a poet too?” And then you write your crap poem about autumn leaves and you realise these things quite soon. I like writing plays because you can hide behind your characters and say, “That’s not me.” You can borrow other people’s voices. I just find it hard to do what my dad does which is to say, “I believe this and this is how the world is.” I like having two people argue about what the world is. And then I suppose another factor might be that the most annoying, but also the most entertaining, people at Oxford were thesps. I went to an all girls school and they just didn’t let us ever direct. I thought that was a shame. As soon as I got to Oxford I tried to direct.

Did you act?

I get stage fright. I can’t act at all. I once played Shylock at school. My mum and dad said, “You really should try and play Shylock.” My mum’s a Shakespearian. We did an abridged version. In the last scene he keeps saying, “A Daniel come to judgment, yea a Daniel.” He’s quite repetitive in his lines. I got completely lost in the scene and I was so out of it, I wasn’t in it at all.

How were you first seduced by theatre?

My dad had a play on while I was at Oxford, 1953 at the Almeida directed by Patrick Marber. You can see how you’d think, this is just the coolest world ever, wouldn’t you want to be part of it? Even before that my dad wrote this opera The Electrification of the Soviet Union. I must have been 11 and again that seemed amazingly cool to be backstage. It’s all those corny greasepaint memories.

When did the writing start?

I wrote down dialogue while I was writing letters to my parents in my year out and when I was working in a restaurant I wrote a short play about waiters. I was writing short stories at the time and finding it quite hard. Weirdly it was the River Cafe. Richard Curtis wrote the Skinhead Hamlet. I said, “We should do the Skinhead Hamlet and I’ll direct it.” The chefs could just about manage the dialogue as it was what they were saying anyway. I thought I really should write a play about chefs and waiters in a high-end restaurant, lots of short scenes. My agent took me on quite boldly just from this, which has never been done.

Was there any form of deafness in your family background that sparked Tribes (pictured right by Simon Annand)?

Was there any form of deafness in your family background that sparked Tribes (pictured right by Simon Annand)?

It was a combination of kernels. It wasn't that I had this deaf friend. It was that there was some dyslexia in my family. I thought it was interesting that someone in a very literary family was not part of the tribe obviously. I thought, what if you take that several steps down the line to make it more extreme? At the same time I watched a documentary about a deaf couple who wanted their baby to be deaf. It sounds bizarre but it’s like, oh it’s got your blue eyes, you’re one of us.

What did your family member know about the play’s relevance?

Of course they knew. I wouldn’t spring that. Also my family all read my plays. Also I conflated so many different parts of different people. So it was fine.

What did they make of the play?

Hm. They were just coming at it very pragmatically. It wasn’t “Oh my god you took my life!” All of that would have happened months before seeing it, on reading the script. Then it was more, “Fucker, you took that joke I made. You look like a witty writer but I made that joke.”

They must know writers steal.

Yeah, yeah, they’re well trained in it from our dad. It’s like Velcro. They just pick up everything.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Beautiful Future is Coming / She's Behind You

A deft, epoch-straddling climate six-hander and a celebration (and take-down) of the pantomime dame at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Beautiful Future is Coming / She's Behind You

A deft, epoch-straddling climate six-hander and a celebration (and take-down) of the pantomime dame at the Traverse Theatre

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Add comment