The Royal Ballet in Cuba, More4 / The Rite of Spring, BBC Three | reviews, news & interviews

The Royal Ballet in Cuba, More4 / The Rite of Spring, BBC Three

The Royal Ballet in Cuba, More4 / The Rite of Spring, BBC Three

Swine flu, bodacious ballerinas, pole-dancers and Christmas bingeing

There were some odd sights in Christmas Day viewing but none more discomfiting, I’d bet, than seeing a ballerina lying on a physio’s couch having a leg dragged quickly up to touch the side of her head while the other leg lay perfectly still pointing downwards. Can the body really do that? Another weird sight - dozens of people in full 18th-century French costume and wigs dancing in 40-degree heat on a Cuban stage.

This may have been what TV executives were thinking of when they packed pretty much an entire year’s quota of dance programmes into the brief Christmas period. Among other things during Christmas lunch you could catch the eventful and moving documentary about Brazilian kids' hopes for a ballet career, Only When I Dance, on Channel 4, which I have heartily praised before, but overall an impressive PR campaign appeared to have been waged for the Ballet Boyz, the two dancers who are now virtually ubiquitous as producers and presenters of dance programmes. Which is a good thing, as Michael Nunn and William Trevitt are the Betjemans of ballet TV, and have an eye for the eccentricity of their craft as well as passion for it.

Last night, spread across an hour and a half of prime post-prandial Christmas movie time, More4 paraded The Royal Ballet in Cuba, a Ballet Boyz documentary about last summer’s drama-packed trip to Havana by our flagship company. Immediately after the Cuban saga, you could have caught their Bolshoi film from 2008. Two days before the BBoyz were helming an unorthodox Rite of Spring version created by “the community” for BBC Three, reflecting more a flotilla of little dinghies than a flagship.

With winning charm, and an eye to the widest possible public appeal, they went to breakdancers, pole-dancers and an amateur tango club to recruit their cast

The Rite of Spring was a feast of British eccentricity, the fruit of today’s obsession with democratising dance. With a vague reference that about a century ago Nijinsky and Stravinsky shocked the public with their version of The Rite of Spring, Nunn and Trevitt had carte-blanche from the BBC to make an equivalent to astonish us in today's terms. With winning charm, and certainly an eye to the widest possible public appeal, they went to breakdancers, pole-dancers and an amateur tango club to recruit their cast.

Stravinsky’s music was generally accounted impossible to dance to in a generation where beats come four-square. The choreography was parcelled out along with CDs: the breakdancers left to themselves, the tango and pole-dancers ruthlessly organised by the draconian West End choreographer Paul Roberts, and the camera and editors ordered to cover up the joins and bad bits, and generally turn it into an entertainment package.

Which largely was achieved. Three-quarters of the film was about the process (naturally), because it’s fun meeting sixtysomething Jeanie at the tango club, who looks like a blonde Martha Graham and hence was cast as the lead witch, but kept weeping at the prospect of learning any steps she didn’t already know, and even more fun to hear Roberts snapping at the pole-dancing contest that there weren’t any ”bodacious enough bodies” to put on TV.

The hip hop school was a revelation of the strict discipline that now pertains in that explosive new area of dancing, and in the final performance b-boys, pole-dancers and tangoists, when all dressed in black and chains, and placed in what appeared to be a Shoreditch dungeon for the filming, fused into a rather frightening tribe. Even Jean looked terrifying. It could have been something genuinely innovative had it taken place without the awkward audience participation, which turned the whole exercise back into an amiable community event, rather than anything more interesting.

Whereas the Royal Ballet’s trip to Cuba was both. This was presumably intended to immortalise the glorious progress of a ship of state to a foreign land to conquer with its sophisticated arts, but destiny thought otherwise. Due allegedly to kissing a Cuban official at the airport, six dancers picked up swine flu and were promptly isolated in a hotel, while the company was unloading container after container of major scenery at a cost of a million quid a week and the Royal’s sweating director was desperately switching programmes and borrowing Cuban ballerinas.

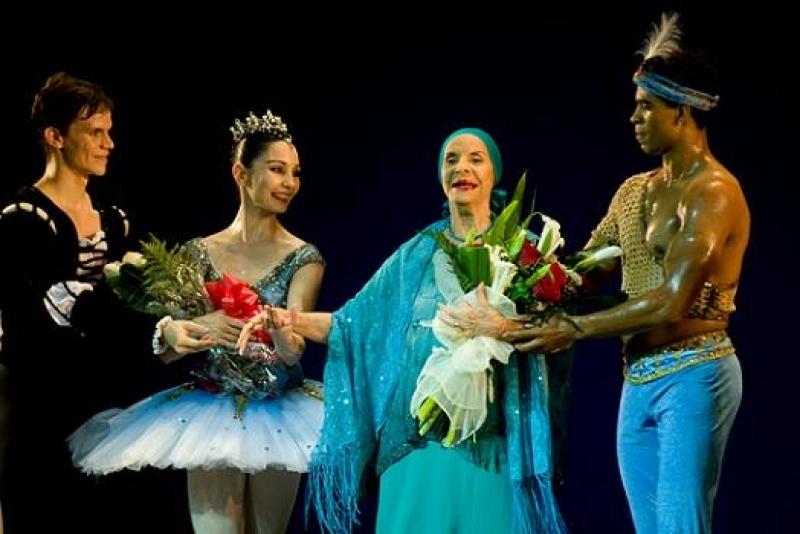

The heat stunned the British artists, though not, fortunately, the two most important ones, Carlos Acosta, a native Cuban who had largely enabled this monumental trip, and his partner the amazing Tamara Rojo. Small, black-haired and definitely what Paul Roberts would consider bodacious, she was last seen balancing on one foot for an illegal amount of time in a duet with a dancer who had only just flown in and with whom she had half an hour’s rehearsal where normally she would have a week.

There was another film struggling in vain to get out of this official chronicle, which remains yet to be fully made. Nunn and Trevitt, attempting to get to the “real” Castro’s Cuba, stumbled upon a barber who told them without guile about his compatriots’ fanaticism for ballet. The ticket queue for the Royal Ballet’s Manon began two days before the box office opened. Nunn was almost speechless at the simple pleasure expressed by people in the line. This was truly art embraced as a community event - but not in the British sense of including all in participation. An old man in the queue said, “This is culture. It makes people happy. It’s just fun.”

What the old man evidently meant, and what Acosta, Nunn and other ballet dancers know - if they could have brought themselves to confess it openly - is that there is a difference between something the community does, and something an elite do to please to the community. The Royal Ballet have never had such joyously eloquent advocates as that Cuban ticket queue for why good art is the best kind of community art.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment