theartsdesk at the Glasgow Jazz Festival | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Glasgow Jazz Festival

theartsdesk at the Glasgow Jazz Festival

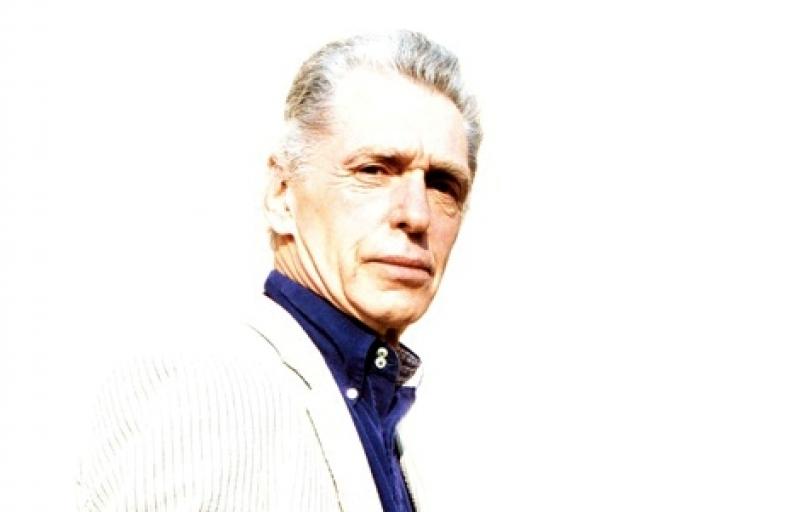

Georgie Fame headlines a festival of manic and restrained pleasures

“It was a bit leary,” Georgie Fame recalls of a 1960 visit to Glasgow. “They had these cast-iron ash-trays at the Empire...” Teddy boys offended by Fame’s starry effect on the local girls led to these being skimmed at the band, bisecting a cymbal, he explains almost fondly, of the night police with dogs were needed to ensure that he at least left the city intact.

That stereotypical picture of a Glasgow crowd was of course unlikely to recur now Fame is a respected 70-year-old, headlining the Glasgow International Jazz Festival’s penultimate night. In steep contrast, this festival's fans are notable for their respectful enthusiasm for jazz in its many 21st century forms. Though Burt Bacharach and the Blind Boys of Alabama were among the week's international headliners, there’s little Cheltenham-style pop outreach on the bill for jazz-fearers. It’s also cursed by bad luck: Sunday’s closing act, the iconic 86-year-old English pianist Stan Tracey, cancelled with illness that morning. But, emphasising young Scottish talent over festival circuit regulars, this was a festival of surprising pleasures.

Georgie Fame hardly counts as that, half a century in, but he has stayed happily steeped in the culture of obsessive, America-revering record-collecting which spawned the Sixties British charge, from Stan Tracey to the Stones. Fame still sees himself as a conduit for greater talents, intimately, in stories of sharing whiskey with Hoagy Carmichael and inadvertently helping form the Jimi Hendrix Experience, or simply by name-checking Ray Charles and co. as he sings their songs. With his sons James and Tristan on guitar and drums, his Hammond organ groove unites middle-aged Mods – one in a brown suit and yellow shirt which looks splendid, not foolish – and younger, pirouetting couples. On Mose Allison’s “Was”, which wonders with quiet desperation whether love, memory and art outlast death, he even manages deep poignancy.

Contrast that with The Ames Room. Walking in near the end of their set, this trio led by French saxophonist Jean-Luc Gionnet smack me round the head with short pieces of bruising intensity. Like those legendary Jesus And Mary Chain gigs which lasted 15 minutes and caused riots, any song they play could almost be enough. Gionnet’s sax can sound like a car horn rammed down during a crash. He leans forward as if into a gale of his own making, while straight-backed, straight-faced bassist Clayton Thomas tolls lone notes, and Will Guthrie gives brittle cracks on the drum. Even they grin nervously, between songs of instantly total volume and velocity. “That was fucking mental,” a listener gasps, staggering for the door.

Contrast that with The Ames Room. Walking in near the end of their set, this trio led by French saxophonist Jean-Luc Gionnet smack me round the head with short pieces of bruising intensity. Like those legendary Jesus And Mary Chain gigs which lasted 15 minutes and caused riots, any song they play could almost be enough. Gionnet’s sax can sound like a car horn rammed down during a crash. He leans forward as if into a gale of his own making, while straight-backed, straight-faced bassist Clayton Thomas tolls lone notes, and Will Guthrie gives brittle cracks on the drum. Even they grin nervously, between songs of instantly total volume and velocity. “That was fucking mental,” a listener gasps, staggering for the door.

The same could be said of Three Envelopes for Edwin Morgan, the Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra’s extraordinary tribute to the titular, great, late Glasgow poet (the GIO are pictured above left). Tam Dean Burn, a firebrand Leith actor raised on punk and Communism, roars out words written and spoken in deepest Scots, arching his back and yowelling like a charismatic, possibly psychotic imp. When he’s joined by the group’s regular vocalist, Maggie Nicols, it sounds like scat-singing in a scene from The Exorcist. Around them, the 25-piece GIO have a mad orchestra’s power. Clarinet and muted trumpet shadow Burn’s agonised cry of “de-e-e-ad”, and the finale is an elegant cacophony. Amid what should be the outer edge of free improv, a high time is had by all. Earlier on Saturday, the GIO were giving courses in this stuff to three-year-olds. Part of Glasgow’s future is in anarchic hands.

The same could be said of Three Envelopes for Edwin Morgan, the Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra’s extraordinary tribute to the titular, great, late Glasgow poet (the GIO are pictured above left). Tam Dean Burn, a firebrand Leith actor raised on punk and Communism, roars out words written and spoken in deepest Scots, arching his back and yowelling like a charismatic, possibly psychotic imp. When he’s joined by the group’s regular vocalist, Maggie Nicols, it sounds like scat-singing in a scene from The Exorcist. Around them, the 25-piece GIO have a mad orchestra’s power. Clarinet and muted trumpet shadow Burn’s agonised cry of “de-e-e-ad”, and the finale is an elegant cacophony. Amid what should be the outer edge of free improv, a high time is had by all. Earlier on Saturday, the GIO were giving courses in this stuff to three-year-olds. Part of Glasgow’s future is in anarchic hands.

These acts, like most of the festival, took place in the beautiful City Halls and adjoining Old Fruitmarket – once just that, and now an atmospheric venue with ironwork balconies and arched roof. On Sunday morning, I walk out of my city centre hotel towards a more obscure destination in the West End. Sauchiehall Street is Glasgow’s main drag, but after crossing a roaring sea of motorway traffic, shops and clubs including the Rennie Mackintosh-designed Willow Tea Rooms and Alan McGee-favoured Nice and Sleazy fade away, along with any sign of bustling life. Victorian and Georgian stone terraces, stained yellow or sooty brown, now mostly offices and hotels in a transient quarter, are set back from the street on a quiet, shut-down Scottish Sunday. A few turnings south, and there’s a sudden clearing at the bottom of the road, the sky opening up above the booming motorway and, beyond it, the Clyde. And here, tucked beneath a railway arch, is the tiny Poetry Club, where the Brodie Jarvie Septet are setting up.

After the effort of getting here, there’s a feeling of peace as Michael Butcher’s soprano sax begins. Drums and bandleader Jarvie’s bass give a frenetic edge and the pianist is the latter’s main foil, but it’s the bright, clean sound of the sax trio which each long piece returns to. Sometimes the music has the pensive noir romance of jazz's post-war New York pomp. The septet aren’t a wholly intuitive band just yet, and there’s the intense flush and effort of youth as Butcher rises on his toes blowing a solo that leaves him breathless. Finding such promising talent on a Sunday afternoon by a Glaswegian motorway, the shush of traffic in the rain and rumble of trains mixed with the music, is a real highlight.

There are others, like hearing Coltrane’s A Love Supreme (pictured left) and Stan Tracey’s Under Milk Wood played on high-end audio systems, the vintage vinyl sounding rich and deep, at Classic Album sessions run for audiences in another corner of City Halls. “No wonder it was so cheap,” one punter mutters, taking noisy leave of the former session, where he presumably expected the long-dead Coltrane in person. It’s the 1976 version of the Tracey album, with Walter Houston reading Dylan Thomas’s poem (the 1965 original, a breakthrough which gave self-respect to British jazz, was only inspired by it). The dozen or so of us listening do so knowing this is sadly the only time we’ll hear Tracey’s hands on the piano today. The acceptance of human frailty and foolishness in both Thomas’s poem and Tracey’s playing is some compensation.

There are others, like hearing Coltrane’s A Love Supreme (pictured left) and Stan Tracey’s Under Milk Wood played on high-end audio systems, the vintage vinyl sounding rich and deep, at Classic Album sessions run for audiences in another corner of City Halls. “No wonder it was so cheap,” one punter mutters, taking noisy leave of the former session, where he presumably expected the long-dead Coltrane in person. It’s the 1976 version of the Tracey album, with Walter Houston reading Dylan Thomas’s poem (the 1965 original, a breakthrough which gave self-respect to British jazz, was only inspired by it). The dozen or so of us listening do so knowing this is sadly the only time we’ll hear Tracey’s hands on the piano today. The acceptance of human frailty and foolishness in both Thomas’s poem and Tracey’s playing is some compensation.

Later that night, Tracey’s old tenor sax compadre on Under Milk Wood, Glasgow’s own Bobby Wellins, 77 himself, is forced to take centre-stage, with the support act’s pianist Steve Hamilton as Tracey’s brave deputy (Tracey, left, and Wellins are pictured above). There’s a frisson missing whenever Wellins turns to him for solos which are at first more flowery than one would expect from the stricken star, though Hamilton settles into his daunting role. Wellins himself, gaunt, hawk-faced and modest, plays short, simple phrases with - on “Monk’s Mood” especially - a tone of bruised, cool romance, and a fading, breathy finish. A crowd not much younger than Wellins have mostly turned up anyway, and seem satisfied by a restrained, conservative, heartfelt set.

Later that night, Tracey’s old tenor sax compadre on Under Milk Wood, Glasgow’s own Bobby Wellins, 77 himself, is forced to take centre-stage, with the support act’s pianist Steve Hamilton as Tracey’s brave deputy (Tracey, left, and Wellins are pictured above). There’s a frisson missing whenever Wellins turns to him for solos which are at first more flowery than one would expect from the stricken star, though Hamilton settles into his daunting role. Wellins himself, gaunt, hawk-faced and modest, plays short, simple phrases with - on “Monk’s Mood” especially - a tone of bruised, cool romance, and a fading, breathy finish. A crowd not much younger than Wellins have mostly turned up anyway, and seem satisfied by a restrained, conservative, heartfelt set.

It’s not a pulse-pounding finish. Instead the festival ends with quiet smiles of satisfaction, amidst murmurs of disappointment. It’s been that sort of weekend.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

theartsdesk Radio Show 37 - Pete Lawrence of the Big Chill discusses the power of protest music and his new project This Is The Fire

Talking to cultural activist Pete Lawrence – camp outs, singalongs and saving the world

theartsdesk Radio Show 37 - Pete Lawrence of the Big Chill discusses the power of protest music and his new project This Is The Fire

Talking to cultural activist Pete Lawrence – camp outs, singalongs and saving the world

Album: Sabrina Carpenter - Man's Best Friend

Short but not so sweet

Album: Sabrina Carpenter - Man's Best Friend

Short but not so sweet

Album: CMAT - EURO-COUNTRY

The flame-headed chanteuse with the comic touch hits pop perfection

Album: CMAT - EURO-COUNTRY

The flame-headed chanteuse with the comic touch hits pop perfection

Album: The Hives - The Hives Forever, Forever The Hives

No power ballads, no acoustic interludes - just speedy rock’n’roll all the way

Album: The Hives - The Hives Forever, Forever The Hives

No power ballads, no acoustic interludes - just speedy rock’n’roll all the way

Album: Benedicte Maurseth - Mirra

Haunting, intense evocation of Norway’s uplands and its wildlife

Album: Benedicte Maurseth - Mirra

Haunting, intense evocation of Norway’s uplands and its wildlife

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Album: Nova Twins - Parasites & Butterflies

Exciting London duo turn inward and more introspective with their third album while retaining their trademark hybrid sound

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles - What's The New, Mary Jane

John Lennon’s queasy, see-sawing oddity becomes the subject of a whole album

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

The Maccabees, Barrowland, Glasgow review - indie band return with both emotion and quality

The five-piece's reunion showed their music has stood the test of time.

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Album: Blood Orange - Essex Honey

A triumph for the artist who doesn't clamour for attention but just keeps growing

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Houghton / We Out Here festivals review - an ultra-marathon of community vibes

Two different but overlapping flavours of subculture full of vigour

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Wolf Alice - Clearing

Ten years from their debut, Wolf Alice once again make magic from the familiar

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Album: Deftones - Private Music

Deftones give us a glimmer of hope, but that's all...

Add comment