Different Drummer: the Life of Kenneth MacMillan | reviews, news & interviews

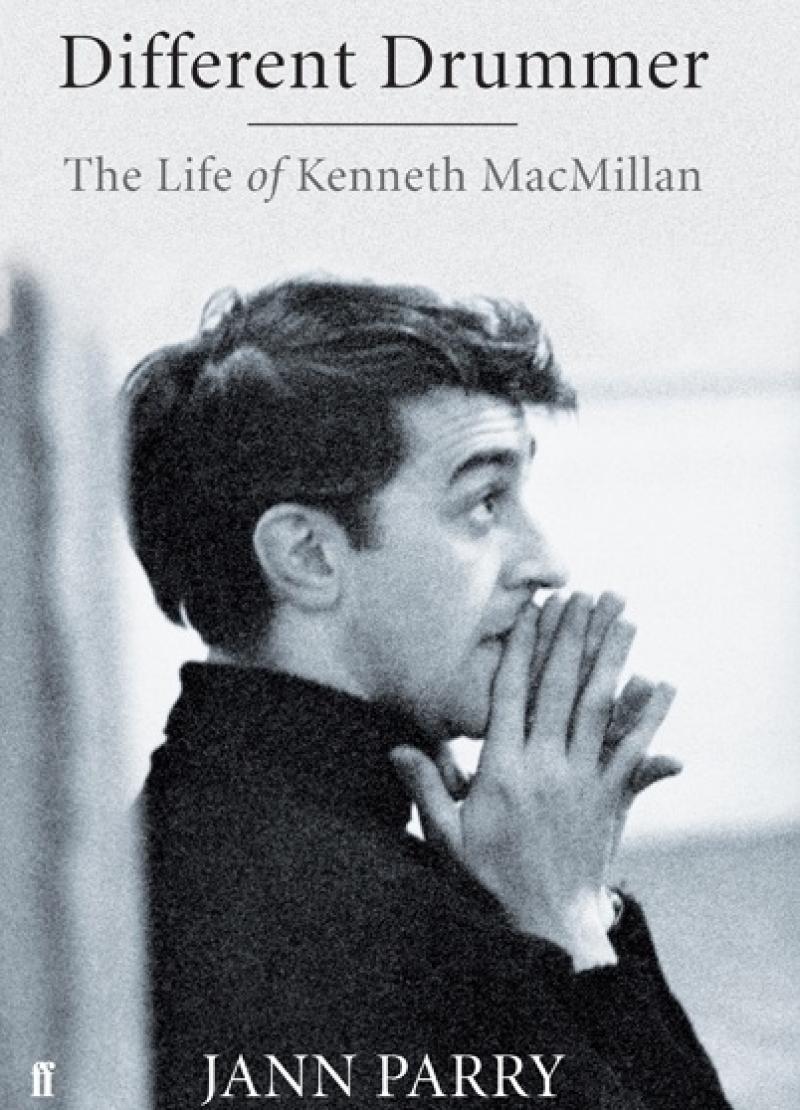

Different Drummer: the Life of Kenneth MacMillan

Different Drummer: the Life of Kenneth MacMillan

Interview with Jann Parry, calm biographer of ballet's shock creator

The spy out in the cold, the alienated Heathcliff of ballet, rough-hewn, moody and a little frightening - this is an image that’s commonly paraded of the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan. His ballets stand up that image, staging barely watchable sexual urges (The Judas Tree, My Brother, My Sisters), accusing polite society as a force for evil (Mayerling, Las Hermanas), smashing the porcelain in ballet’s china cupboard.

Outsiders in ballet tend to attract excitable biographers, focusing joyously on the contrast between establishment and maverick, parodying the fairyland side in order to relish more its invasion by beatniks. Today's public is more accustomed to getting the personal angst shtick rather than enumeration of the truth that ballet is above all about unceasingly hard work, self-discipline, and a constant renewal of craft. Ballet’s not for the thin-skinned arty-farty; it’s ruthless, it kicks out all but the most hard-working, and only the most supremely hard-working get to the top, as MacMillan did, or have the posthumous global acclaim of being the author of two or three of the most sought-after dramatic ballets in the Western classical world, 17 years after his death.

Hence the value of Jann Parry’s landmark biography of MacMillan, Different Drummer. It is huge, almost 750 pages, but with this man and these ballets, it’s necessary to tread cautiously through minefields, not to leap to glib judgments about a working-class, childhood-trauma wreck thrown to toffee-nosed establishment wolves who didn’t understand his modern brilliance. The lapse of time since his death in 1992 has given a valuable perspective. Calm and clear-eyed, Parry, The Observer's dance critic for 21 years and a former BBC World Service producer, teases out from the emotional barbed wire littering his lifestory that in this most collaborative of artistic worlds, it is never possible genuinely to be a loner. She sympathetically unpicks the facts of a childhood spent in wartime, of disruption, bereavement and emotional disorientation that laid the ground for MacMillan’s highly personalised thematic material, but she also clarifies what a wretch of a human being he could be, spoilt, manipulative, sponging, in his unhappiness.

An even more unhappy tale emerges from the events and reports she unearthed from inside the Royal Opera House labyrinth. Her biography is an autopsy not only of MacMillan as a man and creative figure but of a Covent Garden world that had become almost self-mutilating, in which normal decision-making responsibilities were too often ducked, bucks eagerly passed around corners, class prejudice ruled, and artistic loyalty to colleagues was rare. As Parry explains below in an interview with theartsdesk below, the only place this choreographer felt was in the studio, with his allies, the dancers, making up a story. That was where his truth lay; the outside stuff, the politics, the media, the daily grind, was the lousy fairytale.

Yet although the title focuses the spotlight on MacMillan’s sense of being out of step with the norm, what Parry crucially uncovers with her painstaking work is how devoted and attentive he was to his demanding art and the organisation he worked for, how he rose again and again from personal crises to deliver meaty, provocative, innovative classical works that kept what ballet was all about constantly debated, and have not been equalled by his successors in the combining of stage sophistication with psychological acuity.

Many questions are answered about his relations with Frederick Ashton, the good fairy of British ballet in American eyes, to whom MacMillan had always to be the bad one. They danced the Ugly Sisters gleefully together in Cinderella when MacMillan was young, both spiky, self-absorbed personalities, warily appreciating each other’s work but soon not brothers-in-arms at all. Ashton’s infamous lack of support of MacMillan over the casting of Fonteyn and Nureyev for the premiere of Romeo and Juliet is tempered by Parry’s exposure of MacMillan’s own unreliability on barricades. Ballerina Lynn Seymour’s viewpoint on the key creative collaboration between dancer and choreographer in the past half-century, hers with MacMillan, exposes a minefield of professional and personal conflicts and betrayals. De Valois's undoubted prizing of MacMillan's questing talent was more than once combined with a bit of backstabbing. When Parry lays out the disgracefully confused conditions that the Opera House bequeathed him when appointing MacMillan as Royal Ballet director, condemning him and new music director Colin Davis as lower-class, the entire place looks like an asylum full of lunatics.

To find any correlation between MacMillan’s odd and almost determinedly suspicious personality and the bang-on psychological understanding that impels his best work is probably easy; what’s harder is to explain the switch he could evidently throw, even in his most manic sufferings, when he walked into a ballet studio. In there, he quickly, calmly, unhysterically wrote out his livid stories in a language that only a master of academic ballet steps could write. It is also impossible from here to see what will last.

Certainly you couldn’t have omelettes without a lot of broken eggs and there are plenty of broken or addled works lying around that prove hard to revive (last season Isadora, cleaned up, filleted and julienned by MacMillan’s widow, Lady Deborah MacMillan, was a cold salad compared to the hot gristly experimental goulash of the original). Some of those strange one-acters have yet to find their time, and Parry’s careful descriptions should ensure that today’s taste decisions don’t overrule future possibilities.

Different Drummer as a title may be right. Most people need to be loved; MacMillan, reticent, ill at ease, rapacious of others’ lives and feelings without feeling responsible for them, obsessively scratching at his own scars without truly seeking healing, probably needed not to be loved in order to work. No wonder Jann Parry took 17 years to write about this perplexing, stimulating, irreplaceable man.

ISMENE BROWN: How did you decide to approach this biography? With a man who generates such emotion about him and his work, I imagine there were a number of different ways to go.

ISMENE BROWN: How did you decide to approach this biography? With a man who generates such emotion about him and his work, I imagine there were a number of different ways to go.

JANN PARRY: I hadn’t thought of doing it at all. I was approached by Deborah MacMillan who asked me if I would do it because Kenneth had thought my review of The Judas Tree showed I was more or less on his wavelength. The task of biography was daunting as I hadn’t done a biography before and I’m not trained for marathons, and I suspected it would be a marathon. But Deborah assured me from the start that it would be no holds barred, and she would not in any way intervene or direct me - except that she was obviously a valuable source of information about him once they met. And all the way through she was patient, because it took me an incredibly long time; she never insisted on seeing anything or stopping me from finding people I wanted to talk to. The biography’s not “authorised”, in the usual sense - in that she only read it for the first time when it was actually published.

There always remains this suspicion about widows and biographies.

You need family permission to get access to whatever material your subject has kept, in terms of letters, notes, documents. Without that you are stabbing in the dark. So the family must be involved, but I was surprised by how hands-off she was. She handed over a trunkful of stuff that he’d pushed into drawers and suitcases, handed over without any queries - including his diaries, which she said she hadn’t read. He kept them only from the late 1980s. They’re not confessional diaries, they’re the any-year diaries, with a date at the top, and he’d draw a line under each entry for each year, which made it quite difficult to keep track of chronology. Notes of ballets, films, plays he’d seen - often with exclamation marks, and no other indication of what he thought. Or when he started a ballet. That’s it. Nothing about what he’s thinking. Just would say: “Started new ballet - hopeless.”

What was in his mind keeping these notes?

Perhaps just keeping track of his life, how long it took him to work on a ballet. Or a note when he told dancers they were no longer to perform in his ballets, or notes on Charlotte growing up, going to school. But I did wonder whether he might have had a plan to write his autobiography, because quite late on, probably around 1990, he did attempt to write his memoirs. There’s quite a thick batch of notes on this, but it turns out he’s going over and over the same ground, of his youth, changing a few words, crossing out, amending, apparently trying to get it as right as possible - and then he gave up.

As his biographer how useful was that to you? Was it an attempt to record childhood events as clearly as possible or a psychological therapy process, working through different feelings?

Both. He was trying to record his own recollections of his emotions at those times, and finding himself surprised he didn’t appear to feel anything. Like his father’s death: he wrote that he sat at the end of the bed and felt completely numb. I think he did want to pinpoint how he felt, because he’d undergone a lot of psychotherapy and related things, so he must have gone over that ground many times. I think he was trying to account for his past.

How do you think he felt about not feeling anything when his father died?

I’m sure he knew this was a source of a lot of angst through all the rest of his life. But his relationship with his mother was even more significant. What astonished me was that in all the interviews I’d read he said he was 11 when his mother died, and she died of a fit while he was there. I checked and checked, and he was actually 12 when she died, and he was away at school. He came back on the train and was told by his father and sisters that she had died, he didn’t even know. He was told by his father not to cry, and to kiss the body. So he made up a story. That is a pretty awful experience - being made to objectify his mother’s dead body like that. I’m reminded suddenly of MacMillan’s so-called necrophiliac duets in Romeo and Juliet or Manon, where you get dying or dead women manhandled as if almost to punch life back into them.

So he made up a story. That is a pretty awful experience - being made to objectify his mother’s dead body like that. I’m reminded suddenly of MacMillan’s so-called necrophiliac duets in Romeo and Juliet or Manon, where you get dying or dead women manhandled as if almost to punch life back into them.

Yes. It sounds crude, like amateur psychology, but it does fit the evidence so closely. You do see over and over in the ballets these limp, lifeless, female bodies being flung about - R&J, Manon, Judas Tree (pictured left, Viviana Durante and Irek Mukhamedov), a TV ballet called the Crimson Curtain.

What did you discover in his childhood that surprised you about his relations with his parents?

That he’d obviously been very close to his mother, and he told a friend that she breast-fed him until he was four - which is possible but surprising. Incidentally, I came across a note from a psychiatrist who saw him that failure to separate from the mother had damaged him. She had indulged him considerably more than his older brother. And Kenneth didn’t like his father, perhaps because he was regarded as this very stern figure. But also when Kenneth was growing up the father was finding it incredibly hard to get work, and while his two elder daughters were employed he wasn’t. Once the mother had died, he certainly drank a lot, and was according to the memoirs very morose. So Kenneth was alone in the house with this bereft and morose and alcoholic father, longing to escape. His older sisters had left home, his brother was away.

I feel from reading your book that MacMillan was despite his adoration of his mother very like his dad, terrified perhaps that he would inherit his depression and weakness. There is that extraordinary scene in Mayerling where in the choreography itself the mother seems to be apologising to her son for saddling him with defective genes.

Kenneth confessed that he was always frightened of being found insane, declare incapacitated, and put into an asylum. Father was deeply gloomy, and one sister became depressed, and Kenneth did become alcoholic like his father, and even replicated his father’s behaviour - which he must have been conscious of from his therapy. The way he behaved in Berlin [in the 1960s, when he was director of West Berlin’s Deutsche Oper ballet], it was like the father of the family of British émigrés, and he behaved towards Lynn Seymour much as his dad had behaved towards his elder sister, in terms of trying to stop her having her own life.

The other point with the mother is that he was riddled with guilt over his feelings about her illness. She suffered from seizures, which I was told was probably Bright’s Disease, some kidney disease not properly diagnosed. So she would lose control in these fits, and he was horribly embarrassed by these. But once she died the boy felt guilty because at times he’d wished she had died rather than embarrass him. And those fits and seizures appear in ballets here and there - the scapegoat sister in My Brother, My Sisters (pictured right) has fits, and in they’re in Playground, a ballet that hasn’t been seen much. Even in Prince of the Pagodas the old Emperor has fits. And Kenneth had this fear that he too would embarrass himself in public by making a spectacle of himself.

The other point with the mother is that he was riddled with guilt over his feelings about her illness. She suffered from seizures, which I was told was probably Bright’s Disease, some kidney disease not properly diagnosed. So she would lose control in these fits, and he was horribly embarrassed by these. But once she died the boy felt guilty because at times he’d wished she had died rather than embarrass him. And those fits and seizures appear in ballets here and there - the scapegoat sister in My Brother, My Sisters (pictured right) has fits, and in they’re in Playground, a ballet that hasn’t been seen much. Even in Prince of the Pagodas the old Emperor has fits. And Kenneth had this fear that he too would embarrass himself in public by making a spectacle of himself.

Did he fear that all his life?

I think so. However many psychiatrists he saw, I don’t think his underlying anxieties ever went away.

One might wonder whether MacMillan in a sense needed to suffer to make his work - whether [as Dr Luis de La Sierra was arguing in a recent conference on MacMillan and psychoanalysis] artists sometimes are frightened to “lose” their neuroses. Did he need that in a way?

I don't think he had any option. He couldn’t escape that side at all. There was nothing psychosomatic about it, I don’t think. He was fascinated by psychoanalysis, but obviously had no fear of consulting them. I think he was fascinated by the probings to see what you might find in your subconscious, and knew he could rely on the fact that he could go into the studio and things would come out that he hadn’t expected. He would let his neuroses and instincts come to the surface in a safe place, the studio.

He used psychoanalysis as a kind of truth drug.

Yes, that’s well put. It was liberating, in a way. It gave rein to his imagination.

So he wasn't in search of a cure.

Only insofar as his everyday living was concerned. He had such neuroses before he got married - he was terrified of aeroplanes, he wouldn’t learn to drive.

He was actually odder than most people, generally.

Yes. He was an inveterate hoarder and collector, so once he got hold of an idea, as a youngster he’d collect shrapnel and souvenirs. he collected costume jewellery. He hoarded wool and became an obsessive knitter and crocheter.

If you look at the works he made in his unhappiest years - say the '60s and '70s - and those he made in his relatively more stable twenties in the 1950s and after he married and became a father, do they say anything about this?

He always had an ability to work. That was something that really surprised me. Even when he was in the most terrible state, refusing to come out of his basement flat, drinking too much, very distressed, and would have to be physically rescued by dancers and friends to get him to the studio - once he was there, he could create. In the 1960s there he was in Seymour Street, worrying, not able to replace the fuse, hitting the bottle - and yet he could create Romeo and Juliet, Song of the Earth. Those are not the ballets of a disturbed mind at all.

But certainly in Berlin, the lowest years of his life, the ballets there do reflect that: Anastasia, and a Cain and Abel ballet about guilt and murder and horror. And again the '80s, when he’s successfully married and his daughter is growing up, he’s making these works that nobody in the Royal Opera House could bear seeing: Valley of Shadows, Different Drummer, even Isadora, with the woman’s sinking into a crazed self-destruction. So I don’t see the pattern. Right at the end of his life, when you might think he’s mellowing, after Winter Dreams and Pagodas, he suddenly comes up with The Judas Tree. I think he carried on being haunted by his demons.

He had a good relationship with them!

Yes, useful creative demons. And he was capable of the lighter side: Elite Syncopations is a very sunny ballet and pure entertainment - and he was perfectly capable of pièces d’occasion and numbers for classics.

What always was there was this work ethic - that’s the extraordinary thing, in the midst of all these neuroses.

And he always had another one on the go. There would always be the next one waiting. Always a pressure within him to make the next work, which you don’t always find with choreographers. Where did the pressure for My Brother, My Sisters for Stuttgart come from? It was just something he needed to get out. And when he had his heart attack and was told to go much easier, because he knew he was on a limited time span, he still was determined to create, and he was assisted by his doctors and by Deborah because he wouldn't have been able to exist without working.

When you think how uniquely in the realisation of ballet you need all these people - they had to agree to look past all this craziness. they evidently knew they could rely on him, basically, when it came to coming up with a theatre production, choreography with a detailed concept of music, theatre, scenery and use of dancers.

Yes, when you think of other choreographers who are so indecisive about a single movement, yet Kenneth MacMillan would turn up and, as I read in the diaries, he’d moan about only doing three minutes today, or scrapping stuff - but he did it. And you think of all these faces standing there waiting to be told what to do. What he feared was loneliness. In the studio people were there, and he knew what he wanted to do. Not what the rules were - but there were parameters he could deal with, objective things.

Though I do wonder - because from the '70s on, he did take a lot of prescription drugs, antidepressants, which slowed him down in order to cope with his anxieties - whether those would have prevented him being able to stand back from his ballets and look at them dispassionately. He could pour the stuff out via the dancers, but could he view them as works that now existed and needed judgment? I probably didn’t realise how addictive those drugs were in those days. The uppers, the downers. In the interviews of that period you hear his voice is slurred and he wears dark glasses. So how do you then look at a ballet? You say in the book that he was never consciously autobiographical in his 90-odd works - how do you account for the prominence of the family in his ballets?

You say in the book that he was never consciously autobiographical in his 90-odd works - how do you account for the prominence of the family in his ballets?

When I asked him about My Brother, My Sisters, when I was writing a preview for Judas Tree, he laughed and said, “Nobody in my family ever killed me.” So it’s an amalgam of families and imaginings (The Invitation, pictured left). And you see over and over dual characters, as if splitting himself in two. The good and the bad, the Madonna and the Whore. But the two male halves would be Kenneth himself split. He admitted that in My Brother, My Sisters he was the “He” who could walk away, not take responsibility. He definitely splits himself into the Cain as well as the Abel.

How much of this derives from his relations with his older brother? Was there never any love lost between Kenneth and George?

Difficult to tell, because I only know Kenneth’s reaction to his brother by what I was told, mainly from Deborah. I did interview George, who is now dead. I got the sense he thought his younger brother had too strong an imagination and made things up. They resented each other as teenagers because the father told George to take Kenneth around with him and the much older George was bored. The split came because of wartime, when Kenneth was evacuated to school and spent most of his growing-up years away. George was indignant, he told me, because he would always send money back from his wages for Kenneth, and then would write to him - then he got a letter from Kenneth saying, “I don’t see any point in continuing correspondence.” I think Kenneth cut himself off from his past, reinvented himself, and had nothing in common at all with George. His brother never came to see any of his ballets - George told me, "Kenneth never invited me." I think Kenneth wanted to distance himself completely from the poverty, in every way, of that background.

I wouldn’t have thought George needed an invitation to come and see his brother’s work... What was that hostility all about? Where did it start? I wonder if Kenneth instigated it - was it important to his art? There are a lot of shady secondary men about in his ballets.

Maybe it was the man without the feminine side. The uncomprehending, macho figure, who would have nothing in sympathy with an outsider. So he could define himself as rejected.

What did you find about MacMillan’s early life that struck you? I wondered if this unusual work ethic showed in him as a child?

It may have been there in his Scottish Protestant background. His school reports were always good, he always had good marks. Once he’d cottoned on to the dance ethic, via his first teachers Miss Thomas and then Miss Adams, they instilled into him that the harder he worked the better he would become. And the scholarship to the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet was his escape route. There was something interesting that Miss Thomas said, that Kenneth did everything to his best - but not for other people, for himself. He was obvious a diligent member of the junior company at Sadler’s Wells, and as one of them told me, we just had to grow up faster then.

He was an ungrown-up lodger, though. An impossible man, judging from some of the behaviour you show in the book.

There was something Deborah said, that when she first met him, having no knowledge of ballet companies, she was struck by how indulged he was. The ballet company was his family. Although they looked out for each other, when they were young everything was done for them, all the travel arrangements, their daily life was structured. They were only responsible for themselves as artists. Once he became a choreographer, and was valuable, he was spoiled totally. If you wanted a cup of tea, a cup of tea was brought. They all knew he was drinking, but nobody stopped him, because they thought alcohol and nicotine were fuelling the creative urge.

Did Deborah want to change his life?

She wanted to enable him to live like a human being. She set about giving his non-ballet life a structure, which was what he was craving. He battened on friends, would always hope other people would cook for him, so she made him eat breakfast properly, tried to persuade him to give up smoking, ran the domestic side for him. And she said that once their child was born it was good for him to have a temperamental, spoilt toddler around.

That changed him!

Yes, he led a very bourgeois life after that. Something he had always wanted was a family, companionship, he wanted to be looked after.

Let’s discuss class and sex. How did they affect Kenneth MacMillan’s outlook?

Certainly class-consciousness affected him. He’d come from a poor background, from people who didn’t expect to make it in the world. He was very wary of expressing himself, certainly on paper. One of the advantages I found was that he would prepare drafts of letters before he sent them, because he wanted to get his English correct - so I had his side of some correspondence. He also felt he couldn’t express himself well enough at board meetings, press conferences, and that the Ballet Subcommittee at the Royal Opera House were self-consciously the great and good. He felt despised.

Was that a working-class chip or a reality?

Certainly there was an element of reality. Sir Claus Moser [Board Chairman] told me that there was a feeling when there was a change of regime in the 1970s, when Kenneth MacMillan became the ballet’s artistic director and Colin Davis became music director, that these were not the kind of people usually expected.

Did MacMillan actually want to keep himself different from the others? Or did he long to belong in that socio-sexual climate, with Royals and all that, that Ashton ruled?

I think he was unsettled both by the social and sexual side of that world. De Valois complained in one of her essays that he wouldn't do small talk. He would just sit and listen to people if he was uncomfortable, he would be silent. And the Peter Darrell/John Cranko gay world he didn’t associate with, and they always said they never saw him with a pal. If he was getting up to anything he never wanted it to be known. Even now I don’t know if he had a rampant but totally secret sex life.

His creations in ballets aren’t actually very sexually explicit - to be precise they’re more about emotional nakedness.

His creations in ballets aren’t actually very sexually explicit - to be precise they’re more about emotional nakedness.

Yes, Sylvie Guillem’s Manon was more about power, the things a girl has to do - she is powerful by becoming an object, she’s unconscious of her sexuality. It’s how he cast dancers - I’m thinking of Alexandra Ferri, the young Lynn Seymour (pictured right with Christopher Gable in Romeo and Juliet). Anya Linden told me it was an allure that drew men to them without them setting out to do so. Darcey Bussell had that when she was young. Maybe in the pas de deux the woman’s body being put into these extreme situations and flung about are the physical expression of the man’s emotions, passion, rather than illustrations of lust.

Let’s talk about his sexuality. You show that he had passions for both women and men, but stay noncommittal about this. My impression is of someone who perhaps just wasn’t very highly sexed, either way. Yet as you reveal most interestingly, there are quite a few girlfriends, and his first real soul mate was Margaret Hill, a girl who one could call an early prototype for Lynn Seymour.

I was surprised by how important she’d been in his growing up, and in discovering who he was. They were twin souls who came together over this car accident they’d had with Cranko, they complemented each other. Everybody I talked to was fascinated by her = she was so quirky, interesting, clearly vulnerable, but also very confident. She was a pretty good performer, because in the Rambert company she had lots of leading roles, valued particularly as a dramatic dancer, and danced both Giselle and Myrtha. But when she moved to the now Royal Ballet, because she was tall she was given non-leading roles. She had this nervous tic, which went away when she performed. She had a whole language of her own - she had nicknames for everything, acronyms for people - she and Kenneth certainly lived together and had a sexual relationship, so she was probably his first lover.

Did he truly love anybody before his marriage, which was quite late in his life?

This wonderfully complicated relationship with Lynn Seymour was certainly a love of some kind, very, very close, though probably not sexual. The love-hate thing, the jealousy, and the strange thing about Mayerling, where he cast her at 40 as a teenage nymphet. Something Glen Tetley told me was that all choreographers tend to fall in love with their dancers, then they drop them entirely to move onto the next one, which is deeply wounding for the dancer.

Deborah said everybody assumed Kenneth was having an affair with Alessandra Ferri, and his daughter Charlotte was jealous of Darcey (pictured left in Prince of the Pagodas with Bruce Sansom), because her father would come home talking about Darcey all the time. And he was obsessed with Frank Frey in Berlin, clearly.

Deborah said everybody assumed Kenneth was having an affair with Alessandra Ferri, and his daughter Charlotte was jealous of Darcey (pictured left in Prince of the Pagodas with Bruce Sansom), because her father would come home talking about Darcey all the time. And he was obsessed with Frank Frey in Berlin, clearly.

What do you think about his and Ashton’s handling of the ballet directorship at the ROH? Which was better?

I think Ashton was luckier. In that he inherited from de Valois a well structured, organised company, including the lieutenants he relied on. I don’t think Ashton was a great administrator, he just had great lieutenants in Michael Somes and Jack Hart, with Madam behind the scenes, and the dancers were kept in great shape by their Cecchetti training, and the school delivered the kind of dancers he wanted. He brought in choreographers like Nijinska, but never programmed any de Valois ballets.

Then you get MacMillan coming in this complete muddle - you read the notes of board meetings and you wonder what they thought they were doing, combining the two companies into one, never sorted out John Field’s relationship with Kenneth, what he would do. And nobody was scheduling rehearsals or casts - it took forever to get that organised, and was mainly due to Peter Wright being brought back from running the Touring Company. So it wasn’t entirely MacMillan’s fault that the whole thing was a shambles.

Why did he take it on?

Because he was ambitious. It was something he really wanted, to be acknowledged.

Did he have an artistic vision as director?

Yes. He brought in a whole lot of choreographers that the Royal Ballet had not used before. A lot of Balanchine, Robbins, other Americans. And he was trying to introduce new European choreographers like Van Manen, Tetley, broadening their horizon to show them a completely different kind of ballets. And he did keep programming Ashton’s ballets. He did have a vision of what he wanted the company - quite Madam-like, the three pillars, pure classics, contemporary classics, new work. The Sleeping Beauty comes back over and over. One thing MacMillan was indignant about was being accused of being set on wrecking the RB’s classical base. He was livid, he said that was the last thing he wanted. (Pictured below, Song of the Earth, with Anthony Dowell, Monica Mason and Donald MacLeary)

That acidic relationship with the Clive Barnes/John Percival critical camp ate away at his authority, his self-esteem.

That acidic relationship with the Clive Barnes/John Percival critical camp ate away at his authority, his self-esteem.

The ROH Board were so impressed by what they saw as powerful critics in The Times and the New York Times, because the Board members didn’t trust their own judgment. They took the views of certain critics as to the state of the Royal Ballet. You think, why would one person, Clive Barnes, turning up from New York once a year have such influence? Clive said to me he was not setting out to destroy MacMillan. There wasn’t a campaign.

Did Clive feel he was being used in that way by the Board?

I don’t think he knew or cared. He went back to New York and would be quite pleased to see the waves he caused. Both he and Percival told me they wrote as they found.

Why did MacMillan take so much notice of them, rather than the highly appreciative Clement Crisp, Nicholas Dromgoole, and the others pro him?

I think because so much attention was paid to the anti camp, his supporters went to the other extreme in case he wouldn’t create again. When I looked at all the reviews, the truth was that it was never totally pro or hostile - people crossed from one side to the other. There wasn’t any campaign saying we must stop this man.

So it was Kenneth MacMillan’s need to find enemies?

Yes, but there were enemies, people who were influenced by the hostile critics and would go about saying Kenneth MacMillan is a disaster.

When was he happiest in his life?

Young, discovering his powers as a choreographer, when he could stop dancing, which he didn’t want to do. He was very ambitious and knew he was getting somewhere. And then again maybe towards the end of his life, when after the heart attack he was relieved to be alive, and stopped taking the anti-depressants and could relax. Deborah said he was extremely loving and affectionate with his family, he had been loved as a child by his mother, and could love his wife and daughter in an unaffected way. He did release that very easily. But then he creates The Judas Tree...

Why did the biography take so long?

I write incredibly slowly! And I was constantly being warned not to jump too definitely on this or that side. Trying to judge from his paranoia, and reading between lines of ROH Board meetings what was not being said, or being edited out - where they really out to get him? Or was it muddle and incompetence? Trying to be fair in talking about Lynn Seymour’s recollections of her years with Kenneth MacMillan and his take on it. Was she deliberately letting him down or was he being unreasonable?

You’ve written what you found.

Yes.

- Different Drummer: the Life of Kenneth MacMillan won the Society for Theatre Research's book of the year 2009 award

- Buy Jann Parry’s Different Drummer: the Life of Kenneth MacMillan

- The Kenneth MacMillan website

- The Royal Ballet dances MacMillan's Romeo and Juliet 12 Jan-12 March; and a MacMillan 80th anniversary triple bill of Concerto, The Judas Tree and Elite Syncopations 23 March-15 April

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment