Candy Gothic: Tim Burton, MoMA, New York | reviews, news & interviews

Candy Gothic: Tim Burton, MoMA, New York

Candy Gothic: Tim Burton, MoMA, New York

A major retrospective exhibition celebrating the art of a genius director

Though he has yet to make a perfect film, the director Tim Burton’s choice of Gothic and fantasy subjects and his deadpan, post-expressionist approach to them rightfully designate him an auteur of considerable genius. His 14 movies to date have earned him a cohesive retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

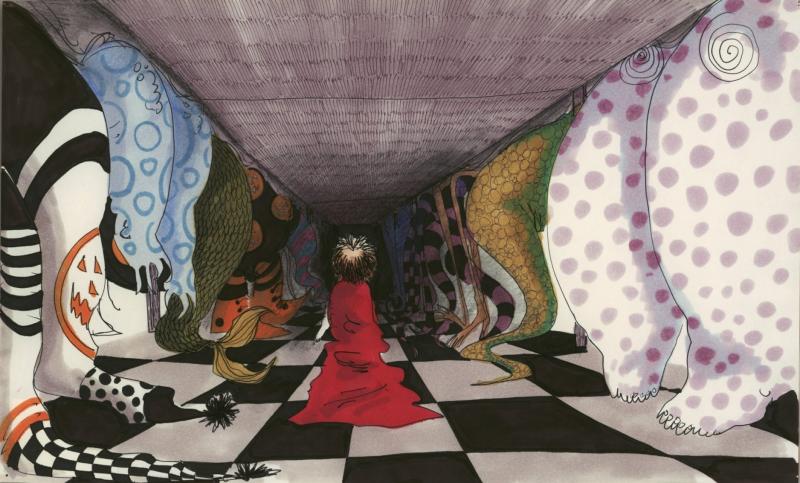

The show is entered via a scary gaping mouth that leads to a low gallery decorated in Burton’s signature black and white stripes; here, a range of monitors show the animated Stainboy shorts Burton made for the Internet in 2000. Aged about six and wearing a superhero’s cape, Stainboy is continually sent by a barking police sergeant to sort out problems in the neighbourhood - Burbank, where Burton was born in 1960 and has worked for Disney and Warner Bros. In the first one, Stainboy haplessly confronts the Girl Who Just Stares until a light fixture made of grapes falls and crushes her, splattering her house with blood. Although it’s more graphically violent than most of Burton’s work, the cartoon is a paradigm of his vision in that it depicts horror from a childlike perspective. The character is pictured below right inThe World of Stainboy (2000), pen and ink, watercolour wash and coloured pencil on paper.

Stainboy, who’s the guide to Burton's website, is one in a long line of quasi-autobiographical child or man-child characters in his films, including Vincent (in the animated short of that name), Pee Wee Herman, Edward Scissorhands, Jack Skellington, Ed Wood, and Charlie in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The gender changes in Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (opening 5 March) but, again, the innocent protagonist is at the mercy of bewildering events.

Stainboy, who’s the guide to Burton's website, is one in a long line of quasi-autobiographical child or man-child characters in his films, including Vincent (in the animated short of that name), Pee Wee Herman, Edward Scissorhands, Jack Skellington, Ed Wood, and Charlie in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The gender changes in Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (opening 5 March) but, again, the innocent protagonist is at the mercy of bewildering events.

The striped gallery leads to a small, dark chamber containing a surreal, illuminated sculpture of a carousel, which is suspended from the ceiling above a pulsating plasma ball and turns to an eerie theme composed by Burton’s most frequent musical collaborator Danny Elfman. Opposite is the figure of the malign, sack-like Ooogie Boogie from The Nightmare Before Christmas, one of Burton’s scariest bogeymen. The exhibition next takes on a roughly chronological shape, following Burton’s early life in Burbank, incorporating his two years of study at CalArts and his four years as an artist at Disney, before sweeping around to a room containing costumes, props, and figures from his films: Batman cowls, the Penguin’s baby carriage, Ed Wood’s pink angora sweater, Edward Scissorhands’ outfit and, in a courtyard, his reindeer topiary. There are thematic diversions within this—a wall of alien and space creature art, for example—and alarming sentinels, such as the lanky cookie-cutter robot from Edward Scissorhands, the sandworm jaws from Beetlejuice, and the spooky animatronic children from Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory.

It’s a thrill to see the materials from the movies, but the essence of the show is Burton’s art, which bears the influence of illustrators like Dr. Seuss, Edward Gorey, and Charles Addams. Slyly humorous, it throbs with tension and frustration. The caption to one wall of cartoons, drawn in pencil on animation registration paper between 1980 and 1986, points out that they were “largely a diversion for the apprentice dissatisfied with his routine animation work at Disney.” One drawing shows a girl listening to a man with bad breath, which teems with all manner of demons. A woman wears a coat made from the fur of animals which are still alive. A couple in love and lust are joined by an arrow, fired by a fiendish little Cupid, that penetrates their heads; this is pictured above left in Cartoons Series (1980-1986), pencil on paper. Another couple holds each other’s separated hands. A teen idol’s upper torso is composed of the heads of his enraptured fans. What links these drawings is their mordant play with embodiment or dismemberment.

It’s a thrill to see the materials from the movies, but the essence of the show is Burton’s art, which bears the influence of illustrators like Dr. Seuss, Edward Gorey, and Charles Addams. Slyly humorous, it throbs with tension and frustration. The caption to one wall of cartoons, drawn in pencil on animation registration paper between 1980 and 1986, points out that they were “largely a diversion for the apprentice dissatisfied with his routine animation work at Disney.” One drawing shows a girl listening to a man with bad breath, which teems with all manner of demons. A woman wears a coat made from the fur of animals which are still alive. A couple in love and lust are joined by an arrow, fired by a fiendish little Cupid, that penetrates their heads; this is pictured above left in Cartoons Series (1980-1986), pencil on paper. Another couple holds each other’s separated hands. A teen idol’s upper torso is composed of the heads of his enraptured fans. What links these drawings is their mordant play with embodiment or dismemberment.

Other drawings exhibit weird or dangerous incongruities: a howitzer arises from a pram and a soldier with a machine gun from a jack in a box. A blue-spotted mechanical toy with a bird’s head fires a lipstick, like a shell. A toy clown pulls a hat open to reveal an army rocket. Everywhere there is tension between supposed innocence and the ability to deal death. One suspects it is not merely mischievousness on Burton’s part but sublimated anger, which is present, of course, in his two Batman films, Mars Attacks!, Sleepy Hollow, and Sweeney Todd: the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Sometimes this anger is tellingly self-reflexive. A mushroom-shaped celebrity creature with a huge toothy grin inflates himself with a pump while his other hand takes the shape of his fans and a paparazzi. The tail of a puppet becomes the gloved hand than manipulates it. A boy cast in resin stands aghast having hammered nails into his eyes: an Oedipal fantasy if ever there was one.

The ghoulish side of Burton is well represented in his images of women who’ve been stitched together post-mortem, an idea he may have got from a photograph of one of Jack the Ripper’s victims. Sally, the stitched-up girl in The Nightmare Before Christmas, appears as her stop-motion puppet self trussed up in a barrow, while Catwoman’s leather costume with its trademark sutures lies on the floor, as if tossed aside by Selina Kyle herself. Dominating one wall is a cartoon portrait, from around 1997, of a much-sutured, blue-skinned redhead sitting at a table in front of a wine glass and a bottle with a skull and crossbones in place of a label (a sutured clown holds the same elixir of death in a splashy painting). The girl wears a black and white striped strapless dress over her gargantuan breasts and a perplexed expression, and she bears a resemblance to Burton’s onetime girlfriend Lisa Marie. It’s tempting to suggest that eros and thanatos meet in the painting, but it’s hardly erotic (indeed, sex hardly ever obtrudes into Burton’s world). A companion Polaroid of a real-life sutured redhead in a blue dress holding a sutured baby doll with pins in its head and with a skull at her feet borders on the arch. Pictured above right: Romeo and Juliet (1981-1984), pen and ink, marker and coloured pencil on paper.

The ghoulish side of Burton is well represented in his images of women who’ve been stitched together post-mortem, an idea he may have got from a photograph of one of Jack the Ripper’s victims. Sally, the stitched-up girl in The Nightmare Before Christmas, appears as her stop-motion puppet self trussed up in a barrow, while Catwoman’s leather costume with its trademark sutures lies on the floor, as if tossed aside by Selina Kyle herself. Dominating one wall is a cartoon portrait, from around 1997, of a much-sutured, blue-skinned redhead sitting at a table in front of a wine glass and a bottle with a skull and crossbones in place of a label (a sutured clown holds the same elixir of death in a splashy painting). The girl wears a black and white striped strapless dress over her gargantuan breasts and a perplexed expression, and she bears a resemblance to Burton’s onetime girlfriend Lisa Marie. It’s tempting to suggest that eros and thanatos meet in the painting, but it’s hardly erotic (indeed, sex hardly ever obtrudes into Burton’s world). A companion Polaroid of a real-life sutured redhead in a blue dress holding a sutured baby doll with pins in its head and with a skull at her feet borders on the arch. Pictured above right: Romeo and Juliet (1981-1984), pen and ink, marker and coloured pencil on paper.

This is a hectic, pop-crazy show that doesn’t demand much in the way of contemplation, but I did find myself lingering in front of specific exhibits for minutes at a time. A case in point was the storyboard for The Nightmare Before Christmas (which was conceived and produced by Burton and directed by Henry Selick). Done in a Gorey-like etching style, in black and white and fierce orange, it depicts the spidery, hunted figure of Jack Skellington and his ghost dog Zero ascending a hill where pumpkins grow under a grove of bare trees - a great, jagged-tooth pumpkin glows like a moon in the sky.

The Gothic, rural spirit of Halloween is beautifully conveyed by this sinister yet comforting little drawing.Helena Bonham Carter, Burton’s partner, is pictured left with the director on the set of Sweeney Todd. In Alice, she plays a combination of the Queen of Hearts and the Red Queen from Through the Looking-Glass, and, as the trailer fleetingly shows, her cranium is much larger than it is in reality. Both her red hair, styled into two enormous poufs, and her face, thanks to a deep widow’s peak, are, in fact, shaped like hearts. The drawing of her at MOMA shows a small, truculent woman with big eyes, a heart for a mouth, and more than a dash of the Virgin Queen. It will be interesting to see how Bonham Carter reconciles what Lewis Carroll described as the Queen of Hearts' “ungovernable passion” with the Red Queen’s “cold and calm” passion.

The Gothic, rural spirit of Halloween is beautifully conveyed by this sinister yet comforting little drawing.Helena Bonham Carter, Burton’s partner, is pictured left with the director on the set of Sweeney Todd. In Alice, she plays a combination of the Queen of Hearts and the Red Queen from Through the Looking-Glass, and, as the trailer fleetingly shows, her cranium is much larger than it is in reality. Both her red hair, styled into two enormous poufs, and her face, thanks to a deep widow’s peak, are, in fact, shaped like hearts. The drawing of her at MOMA shows a small, truculent woman with big eyes, a heart for a mouth, and more than a dash of the Virgin Queen. It will be interesting to see how Bonham Carter reconciles what Lewis Carroll described as the Queen of Hearts' “ungovernable passion” with the Red Queen’s “cold and calm” passion.

Everything augurs well for the film, not least because Burton looks to have been inspired by Tenniel’s Alice illustrations as well as by Carroll. It is a feast to salivate for, but until it arrives Burton followers and anyone curious will have more than their plates full in New York.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...