Q&A Special: Conductor Sir Simon Rattle | reviews, news & interviews

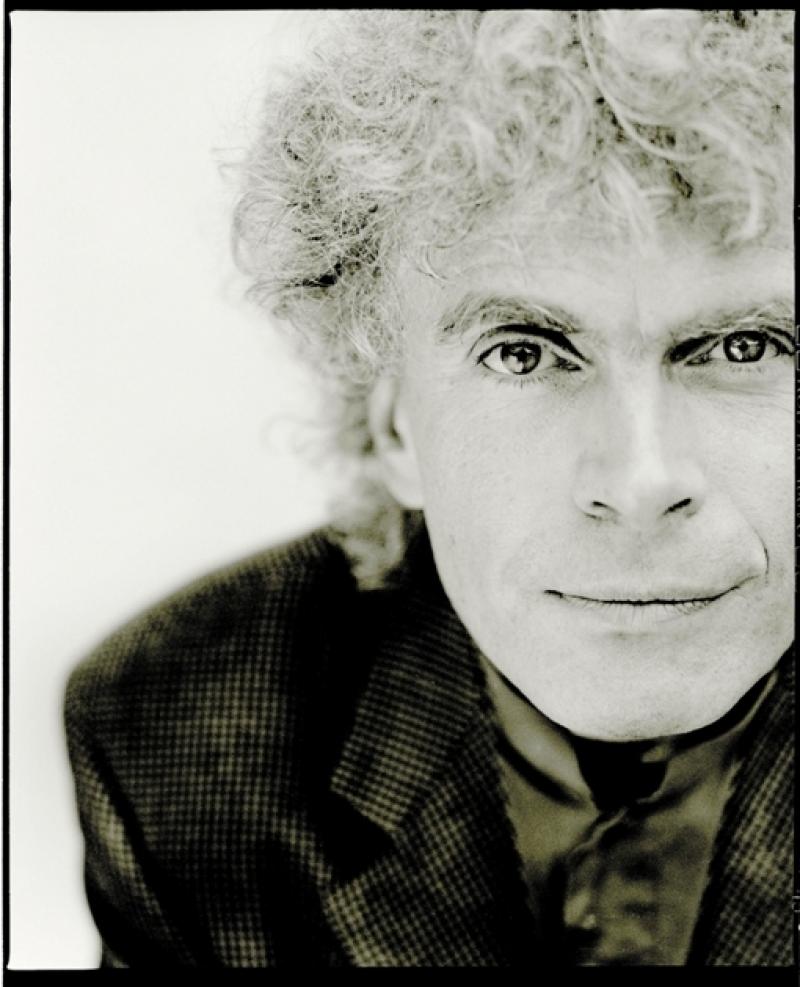

Q&A Special: Conductor Sir Simon Rattle

Q&A Special: Conductor Sir Simon Rattle

The conductor on his long-running association with period specialists the OAE

Sir Simon Rattle (b. 1955) and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (est. 1986) have been together from the beginning. Founded by period-instrument musicians eager to run their own affairs rather than play obediently for conductor-managers like Christopher Hogwood and John Eliot Gardiner, the OAE invited Rattle to conduct a concert performance of Idomeneo in that first year.

There have since been many highlights in the relationship, some of them forays away from the Age of Enlightenment and deep into the 19th century repertoire. “There is no one else on this planet who is like him,” says Chi-chi Nwanoku, principal double bass and a founding member of the orchestra. “Very few conductors can really make you feel that they’re playing every note with you. His hunger and passion is just pouring out and you just get pulled in.”

There has been only one glitch, when conductor and string section clashed over Rattle’s desire to render Bach’s St John Passion a little less Lutheran and a little more dramatic. In practice it came down to a disagreement over period technique. Despite some musicians’ worry that they had blown it, the relationship was unimpaired. A cycle of Schumann symphonies in late 2008 took past 100 the number of times Sir Simon has stood in front of the OAE on the concert platform, all manic rictus and shaking curls, levitating in that distinct responsive style of his.

In slightly nasal traces of Liverpool still unerased after his 18 years in Birmingham and 11 in Berlin, Sir Simon talks to theartsdesk about his commitment not only to the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment but also to the Berlin Philharmonic and the Simón Bolivar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela.

JASPER REES: If you close your eyes, how do you know it’s the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment you're conducting?

JASPER REES: If you close your eyes, how do you know it’s the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment you're conducting?

SIR SIMON RATTLE: Apart from the fact that everything sounds different from every other orchestra, nothing. It’s very different, isn’t it? You have to understand that I conduct an orchestra of teenagers normally. If you’ve seen the Berlin Philharmonic recently, I’m a grizzly old grandfather. This is like an old rock group that’s been together for ages. Last time I was here we were all having a drink together and one of the violins said, “You’ve got to be very careful around 30 menopausal women, you know.”

But one of the wonderful things about this orchestra is this is a lot of people who decided to commit a unilateral declaration of independence from being owned by single conductors. The period-instrument world was very much like the actor-manager theatres tours of the 19th century. Everybody had their particular style. This was a group of people who wanted to do different things. They wanted to seduce people who’d never worked with them. When they first got together they said, “We want to do Mozart with you, and we want to see if we can get Bernard Haitink to conduct.” Of course he came and he said, “I don’t like the instruments and everything sounds like a cadence to me,” so that wasn’t going to work.

How did they seduce you?

Tim Mason, the cellist, was the one I knew. Most of my very good friends went into this world - lots of people I went through the [Royal] Academy with at the same time. I had the experience with David Munrow who is the great missing link. He hanged himself in his 30s. There are great British musicians out there – Christopher Hogwood, Roger Norrington – but everybody of that generation would say David Munrow was the genius. A lot of us were enormously affected by him. It just took me a little bit longer. For me it was Harnoncourt who made me go back to this. And then when I met Tim... we did a charity concert together for CND, he said, "Simon, everything you’re asking is what we’re wanting to do. For God’s sake, have you thought about making this leap?" That was basically it. So I did their second concert, which was Idomeneo. For all of us it was such a voyage of discovery. It was Peter Hall, not a musician but a person of great instincts, who came and said, "This is the future for Glyndebourne." And who pulled Glyndebourne along.

How revelatory was Idomeneo for you?

How revelatory was Idomeneo for you?

It’s just another type of intelligence, another way of thinking. And we all needed what each other had. They desperately needed someone to conduct them and realise there was something you do with your hands on the moment. This idea that there is a language in the air which you’re part of, there wasn’t much of. With most of the period-instrument conductors, skill with the hands and being able to improvise on the moment wasn’t really what they had. So the orchestra would learn what you had to say and then they would shut you out. I learnt about a hundred new things every day from them and still do. We all learn a lot from each other. The good thing about everybody being together for such a long time is that there is an amazing shared experience. you can immediately tell that. You come to a new piece of Schumann, for everybody it’s a huge steep learning curve: how the hell do we play this? That’s the tough thing but the good thing is everybody’s feeling of togetherness and the willingness to try.

Members of the orchestra say they are all allowed to pipe up?

You should see the Berlin Philharmonic. This is nothing. Occasionally these guys stop piping up. Everybody has their ideas. It’s because everybody is very involved in chamber music as well. It’s also a desperation that at the moment nothing is more important. It’s a kind of tunnel vision.

Why has this association between you and the OAE lasted so long?

I’m very selfish. I do it because I learn such a lot from them. It really is to do with exploring. But we all have to push each other in other directions. And that’s a very good tension. Flying in concert is very good with them because once we are all confident enough it can go in many different directions.

What do you gain from having known each other for so long?

There is a real level of trust and it can get us over bumpy moments. There is humour as well. This is one of the best-read orchestras. You can talk about subjects and writers with these guys that would be hard with many other orchestras. The sheer level of IQ out there is very scary.

Does it show in the playing?

It does, because it also shows that they want to know what it’s about. For a lot of orchestras they would say, "Don’t waste time with that. Just tell us, shorter, longer, louder, softer." Here they pump themselves up with these vitamins. It’s like beachcombing. They’re an orchestra of beachcombers, and that’s one of the biggest compliments.

How do you choose what you want to play?

How do you choose what you want to play?

Pleasure principle. What are we all desperate to do? We did a tour where we did a lot of Brahms and some Schumann and we thought, God, this is wonderful. We have to play more of this. People will come up with ideas. The Rameau project was one of those things I’ve wanted to do since I was a teenager. And people will come up with ideas. The Rheingold idea came from some of the players who said, “How far do you think we could go? Could we ever do a Wagner?” Amazingly enough it seems to have been the first Wagner opera to have been done with period instruments. It was a complete miracle because none of us had the faintest clue what it could possibly be. We didn’t know at all what it would sound like or indeed whether it would work. It could have been a catastrophe because it really could have been just too hard. So part of the thing was this sheer delight in hearing. "Oh, it sounds like this." Some of the sounds were so unexpected. To suddenly find that you have Miles Davis in the middle of your brass section under the guise of a bass trumpet which normally sounds like a stampeding elephant... and you had this unbelievable soft warbling brass sound. And for the singers, the shock of hearing it was really fascinating.

Which of your joint experiments have not worked so well?

I thought the St John Passion really didn’t work. Maybe what I had in mind for it was just too weird for them, which is very very interesting because what is too weird is normally not a problem for them. But it’s like at a certain time with modern symphony orchestras doing another type of Beethoven was a problem for all kinds of people. And maybe if we did it again it would be different. We would learn how to make it work together. Basically, it was "Oh no you can’t do that in Bach."

Did it cause ructions?

Not really. I thought, ooh, this is interesting. But we probably all learnt from it.

Did you learn not to do Bach with them again?

Probably. Yeah. Sometimes it’s a matter of explaining why you want to do it and giving them the time to say why this is a problem. And maybe with all of us approaching it in another way we could do it. It had not occurred to me that it might be a problem with them. And having done it with quite a lot of other groups… it was not anything to do with modern playing against old playing. It was to do with how it spoke and whether it was dramatic or not. It was almost like being in Germany. "No, Bach cannot be that dramatic, and no, you mustn’t ask it to be that and this is just distorting it."

Was it frustrating?

It was weird. But Bach survives everything. I don’t think it was bad but it was an interesting clash of cultures. But it also has to be like that. There is absolutely no point in saying you have musicians with very strong ideas and conductors with very strong ideas and sometimes it just won’t mesh. It was interesting for me at one moment for me to be a bit too Mediterranean. I come from Liverpool. We all have to do Bach. When you do the Passions you wonder why anybody ever bothered to write any other music because there is really everything in there.

Do you work with the Simón Bolivar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela (pictured above) to add to your palette of experiences?

I say everything I do is selfish. That isn’t selfish. You go with that because it is simply the most extraordinary musical education project I’ve seen in my lifetime anywhere. And you have to support it. Now kind of by accident it’s one of the better orchestras you can conduct. These kids are in their 20s now. The kids coming up 10 years younger are going to be even better. And they’ll tell you that as well. I conducted The Planets with an orchestra ranging from seven to 14. A four-year-old played the Vivaldi violin concerto beautifully. Number two violin, seven years old. No problem. Twenty-eight double basses. This is an orchestra of 300. Chavez doesn’t always get a very good press but he knows that this is important. The thing is he’s just cottoned on to that. But the fact is that one of the guys [José Antonio Abreu] who runs it was a politician who had the political will to force it. He was the Minister of the Interior. If he doesn’t get a Nobel Prize I don’t know who deserves it. Do you know how many lives he’s saved? Now it is pushing half a million kids. When I first went there it was a quarter of a million. It was already more than did organised sports.

It’s presumably cheering to see an orchestra being ambassadors for an art form that normally has to fight for elbow room.

It’s presumably cheering to see an orchestra being ambassadors for an art form that normally has to fight for elbow room.

Well, it doesn’t in Venezuela, because it’s cool in Venezuela. Basically the concerts are free because the government thinks the arts are important. It’s like in Cuba where the government thinks health is important so it works. These are very strange societies and very strange governments but you have to look at where certain things work. Music is so often the first thing that gets cut. A few years ago we all thought very very hard and it did seem that some notice was taken in Britain and it seems to be better now than it was. But it’s always a danger. It can save people’s lives in so many different ways. You cut the possibility of people imagining and you don’t know what all the knock-on effects are.

How important is it for you to know know the musicians you conduct?

Of course it helps. But there is a weird thing with music. It’s this language that transcends words and you very often know really intimate things about people without having met them, from body language and from eyes. You can sometimes all think you know each other better than you do. You know very important things without having gone through the social niceties.

With the Berlioz it was as if I’d been playing a transcription all my life. With them the sounds were so different

The orchestra say you make eye contact with everyone. Is that strategic or instinctive?

Instinctive. That’s where the real stuff is. I never thought of it strategically. It’s kind of lonely up there and it’s kind of really nice if you have a bit of contact because you’re not making a sound and it’s very nice if you can enjoy a phrase together. I’d never thought of it as “Oh I haven’t looked at that person: I better had”. Actually you never eyeball a horn player. That’s one of the real rules. You just don’t. They’re stuntmen. You don’t eyeball stuntmen just before they’re about to go near death. That’s really true. You also never tell a horn player you played beautifully last time just before a concert. You see that look. They look at you and they’re always thinking, I could die now. And you know there’s something else behind the eyes. That’s really a truth. And so you have to let them do their very difficult thing without too much disturbing.

How about the OAE horns?

How about the OAE horns?

I sobbed in a concert, which I’ve almost never done – oh I’m going off now – when Roger [Montgomery] played the Dvořák cello concerto [horn solo]. I was completely taken aback. The concert was so amazing. Like, the waterworks. Now that’s very special. It’s also something to do with the particular instrument as well.

How long have you been thinking about the second act of Tristan?

It’s always a matter of leaving it in the fridge to marinate for ages. That will be another real push, the second act of Tristan. We’ve got six offstage horns and four on. We’ll just have to get the best horn players on the planet. But I always thought that piece was Schubert on steroids and with these guys it’ll really sound like that. It’ll be another step into the unknown. We’re all desperate to see what it sounds like. I think it will be astonishing. I’ve done it with the Vienna guys in the State Opera. I think it’s going to be fascinating because there were so many unexpected colours in the Rheingold and we want to push the envelope. Also they sometimes just rehearse something just to see what it will be. They’ve played La Mer but they never did it in a concert; they spent a day just finding the right instruments and seeing what it sounded like. With Berlioz it was as if I’d been playing a transcription all my life. With them the sounds were so different. We’ll do the love scene from Romeo and Juliet with Tristan because all of Tristan is lifted from Romeo and Juliet. It’ll be a sexy evening.

The OAE remains your only British commitment at the moment.

At the moment. I mean very occasionally in Birmingham. It’s a shame. I loved going back to Covent Garden to do Pelléas and Mélisande. I had such a great time. I listen to the LSO. Amazing orchestra. But it’s just not guest conducting time at the moment. I’ve got a very demanding German family and a young family and Magdalena [Kožená, Rattle's wife].

But will you continue to come back to the OAE?

Oh sure. We’ll always be working together. And then every now and then we go back to Mozart and Haydn symphonies that are our kind of centre. It’s another kind of heaven. I always have to make time for these guys.

- Performance photography courtesy of the Budapest Palace of Arts

Rattle conducts the Berlin Philharmonic in a performance of Schumann's Paradies und das Peri

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment