Manon: Shock that turned to respect | reviews, news & interviews

Manon: Shock that turned to respect

Manon: Shock that turned to respect

ARCHIVE Daily Telegraph, 4 July 1998: Once reviled, Manon has become one of contemporary ballet's classic heroines. Ismene Brown explains why we fell for a fallen woman

One of the first, scathing reviews of Kenneth MacMillan's ballet Manon in 1974 nailed it exactly: "It is an appalling waste of lovely Antoinette Sibley who, as Manon, is reduced to a nasty little diamond-digger." In that sentence all the prevailing attitudes about ballet were summed up - the status of classical ballerinas as princesses on pedestals, the duty of ballet to polish their virtuous crowns, the horror of seeing this porcelain beauty smashed.

That review, by the way, appeared not in The Lady but in the Communist daily, The Morning Star. But it was not the only slammer - for Manon, it was widely asserted in the prints, while it had three terrific roles was badly constructed, too long, with terrible music - and not a success. (A New York reviewer urged the public to boycott it.)

A quarter-century has changed all that. Now Manon - with all its faults - has turned out to be that almost unheard-of thing, a new classic. All around the world, the nasty little diamond-digger is clamoured for.

There have been Swedish, Australian, Canadian, Russian, Italian, American and French Manons. This month the Royal Ballet and the Paris Opera Ballet are producing Manon simultaneously; Houston Ballet has just finished a run. The vixen of ballet has taken her place alongside Giselle, Aurora, Odette-Odile and Juliet. All ballerinas want to be MacMillan's wonderfully imagined Manon. How piquant, and how sad, too.

For MacMillan died, unexpectedly, nearly six years ago, and though he had seen Manon working her growing spell on the public, he had not forgotten her initial rejection.

"I just wish he were alive to see it now," says his widow, Deborah, Lady MacMillan. "It was such a failure at its premiere and he was deeply hurt. He had done it as a crowd-pleaser - he was very aware that there was a cloud over his head as Director of the Royal Ballet at that point. I think they only persevered with it because so much money was spent on it. It took quite a while to find an audience."

In the 1990s it seems unimaginable that the work was ever a box-office turn-off. With its steamy mixture of sex and cynicism, of blighted love and diseased society, of girl power and male chauvinism, it has become, ironically, the Royal Ballet's surefire money-spinner. Above all, Manon herself is a dream of a role: real, flawed, vulnerable, instinctively seductive, technically difficult - and hardly ever off stage.

British ballet was unready for fallen women, after 150 years of mesmerisingly chaste heroines

Manon Lescaut is a child of the flamboyantly licentious Paris of the early 18th century inhabited by her creator, the young lusty Abbé Prevost, a priest far more dissipated than would be considered acceptable now. She uses sex to escape poverty. She plays the loving, poor Des Grieux against the ruthless rich Monsieur to whom her brother sells her, and dies a convict. Perfidious, captivating and honest, Manon spawned a century of fallen opera heroines: two Manons, Violetta, Carmen and Tosca among them.

But British ballet in the Seventies was unready for fallen women. After 150 years of mesmerising, chaste heroines, the whole classical vocabulary looked framed to express noble sentiments and romantic, spiritual love.

MacMillan, however, had a genius for inventing choreography of ever more acrobatic eroticism, drawing decidedly on real life. Manon broke the mould of idealised heroines and the taboo on sex. His later works became even more exploring of psycho-sexual behaviour. Feminists attacked him for misogyny.

"Oh, ludicrous," says Lady MacMillan. "We are feminists because of what happened to those women in past centuries. Kenneth was interested in sexually driven people. You could let rip choreographically. I don't think he ever set out to upset or shock. Having grown up in the Sixties, he found it extraordinary that while all this new life was coming in through television and film, in the ballet world people were still pretending that girls had wings sprouting from their shoulders. Manon was one of the seminal heroines in literature - he was always interested in the social mix of extreme wealth and extreme poverty, and one of the few things that could get you from one world to the other was sex."

Whom did he base Manon on? This is a question with an elusive answer.

Until the early Seventies, there was one supreme MacMillan ballerina: Lynn Seymour (pictured left). Her daring, her confessional expressiveness, her cuddly femininity and exceedingly pliable body were written into almost every MacMillan ballet.

Until the early Seventies, there was one supreme MacMillan ballerina: Lynn Seymour (pictured left). Her daring, her confessional expressiveness, her cuddly femininity and exceedingly pliable body were written into almost every MacMillan ballet.

Her biographer, Richard Austin, claims that Seymour was the absent inspiration for Manon - even though MacMillan made the role for Antoinette Sibley. The idea persists today, in part because Manon's reckless sensuality seemed a new departure for Sibley, the consummate classical ballerina.

However, Seymour was by then pregnant, considering retirement from ballet. And Sibley has proof on her bookshelf that MacMillan had her in mind when he began thinking of Manon - in summer 1973 he gave her a copy of Abbe Prevost's novella, Manon Lescaut, inscribing it meaningfully, "Darling Antoinette, Some holiday reading for you which will come in handy March 7, 1974" [the date of the premiere].

Now 59 and a Dame, Sibley is chatty and girly, but has a surprisingly dirty giggle. If anyone doubts her sex appeal, they need look no further than Ashton's scorching choreography for Titania in The Dream, stuff so hot that it gives Manon a run for her money. (Sibley, twice married, once told an interviewer that she was never without a man.)

She and Seymour, she said, were long-time friends and never rivals. Seymour, dark and voluptuous, was MacMillan's muse, but Sibley, fair and mischievous, was Frederick Ashton's post-Fonteyn favourite.

"Lynn and I had no reason to be jealous of each other. Kenneth always chose me as second cast to Lynn in his ballets - I was the original second cast for Juliet. But he had also made several one-act ballets for me and he must have seen something in me that he wanted. Manon was me, this was my ballet." When she dies, if she were the soppy kind, says Sibley, she would wish to expire clutching her Manon and Titania costumes.

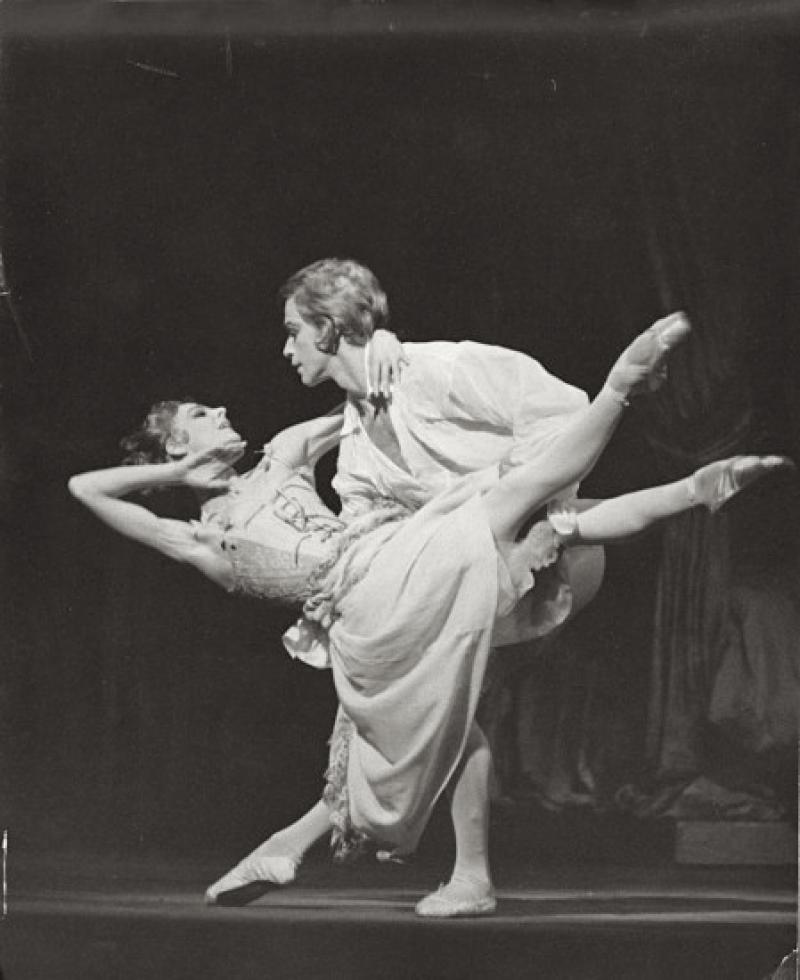

But there is another strong claimant for the inspiration of MacMillan's Manon. Sibley had a persistent knee injury, which hobbled her early on in Manon's creation. She could only watch tensely as Jennifer Penney (pictured right with Anthony Dowell) took over.

But there is another strong claimant for the inspiration of MacMillan's Manon. Sibley had a persistent knee injury, which hobbled her early on in Manon's creation. She could only watch tensely as Jennifer Penney (pictured right with Anthony Dowell) took over.

While Sibley made three of the four memorably inventive pas de deux with Anthony Dowell, MacMillan made the feverish last act with Penney. And there are the two most explicitly erotic, most Manon-ish bits: an immensely knowing trio where her brother pimps her to the rich patron, and, later, the "parcelling out" of Manon, as Lady MacMillan calls it, to a roomful of men to arouse her patron. Penney, in the 1982 video of the ballet, is electric.

But what of Lady MacMillan? For MacMillan was courting her in 1973 while he pondered his new work. (They married shortly after the Manon premiere.) Was Manon at all inspired by MacMillan's intelligent, frank wife?

She laughed uproariously at the idea. "I don't know! It was quite a romantic relationship that we had. I like to tell people that all those pas de deux were worked out on me in the nude.

"Actually, it's nobody's ballet. It's Manon's. And it's provided a chance for umpteen marvellous ballerinas. I think if things had worked out, Kenneth would have worked with Lynn till the day he died - a lot of the things Lynn did people would rightly say nobody could do it like her. But I have seen countless Manons, in countless productions, in many countries. And a huge percentage of them he would have been thrilled by."

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment